Imagine you’re a tiny parasitic worm. You don’t have teeth or claws. Heck, you don’t even have a mouth. Yet you’re expected to make a home in the intestines of crustaceans and fish. Intestines—the darkest, dreariest, most slippery tubes in all of biology, organs designed specifically to remove undesirables from the body. Undesirables like you.

But you’re a Pomphorhynchus laevis, a spiny-headed gut fiend that takes what it wants. All you have to do is ram those little spikes into tissue and inflate your head like a pair of Reebok Pumps. (Your head is actually an invaginating proboscis, but we’re not here to judge.) Once anchored, all you have to do is kick back, relax, and soak up the intestinal nutrients until you feel like moving on up the food chain.

Most people look at creatures like this and suddenly feel the need to wash their hands. But scientists look at parasitic worms and think, “I can’t wait to apply this foul beast to an open wound!”

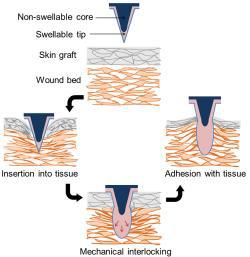

Oh, OK, they aren’t actually putting parasites into human bodies—though doing so might be a new way to treat Crohn’s disease. Researchers at Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital have channeled the spirit of Pomphorhynchus laevis to develop a new design of microneedle useful for attaching skin grafts. The cones of the needles are made of stiff plastic, while the tips are made from a different material that swells up when contacting water.

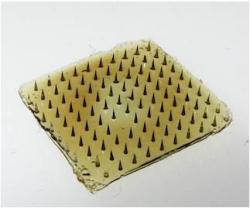

Courtesy of the Karp laboratory

“The unique design allows the needles to stick to soft tissues with minimal damage to the tissues,” Dr. Jeffrey Karp, the study’s senior author, said in a press release. “Moreover, when it comes time to remove the adhesive, compared to staples, there is less trauma inflicted to the tissue, blood and nerves, as well as a reduced risk of infection.”

Karp and team have designed the spike tips’ engorgement to be both fast-acting and easily reversible. Even better, the adhesion strength they provide is three times stronger than conventional surgical staples. (Plus, you don’t end up looking like a zipper.)

This is potentially great news for skin-graft patients of the future, including anyone with burns, infections, some cancers, and the many other holes we have a habit of poking in the epidermis. And since we learned all of this from a creature accustomed to life on the inside, the microneedles ought to work quite nicely for any internal patchwork surgeons require. Finally, the ability to easily and safely penetrate flesh may make the technology useful for better injections from antibiotics to anti-inflammatories.

You have to hand it to the little monster—it just revealed a treasure trove of biomimetic sucking technology. And that’s a heckuva lot more appealing than the other trick up its proboscis: The spiny-headed worm can use mind control to make its host commit suicide. (Sleep tight.)