I’m a gamer, a game designer, and a victim of gun violence. In the current climate, that creates a bit of friction in my life.

When I was a college student in Rochester, N.Y., in 1998, I was shot in the left side of my chest. I was lucky—the bullet basically bounced off my rib cage. I spent a few nights in the hospital, but I escaped serious physical injury (though I was wickedly sore). The 17-year-old stranger who shot me was eventually arrested and served five years for first-degree assault.

After I healed, an alarmingly large proportion of the people who heard my story immediately suggested I get a gun “to protect myself.” I repeatedly explained no, I didn’t want to carry a gun. If I ever actually needed it, it would likely be inaccessible in the bottom of my backpack, or I’d be overpowered and the bad guys would take it away from me. Carrying a gun was not a solution to the random violence I had faced.

After awhile, I just stopped talking about the attack. Before I wrote this piece, even Google didn’t know I was shot—since I was injured during the Internet’s relative youth, no news stories about it were cached. It was my secret to share or not. But now, given the still-going-strong debate over the connection between video games and gun violence, I decided it was time to start talking again.

It’s hard enough to explain that you’re a victim of gun violence under the best of circumstances. Most people respond awkwardly (if they acknowledge it at all) or gift me with some awful conspiracy-theory political commentary that’s worse than Facebook saber-rattling. At least this time around, no one has suggested to my face that I arm myself. But the get-yourself-a-gun discussion was easy compared with the one I have to have now. Now people fixate on the fact that I’m a victim of gun violence and that I make video games for a living.

I’ve worked on hundreds of games, mostly for children and across all sorts of platforms (Web, mobile, and console) for some of the most beloved brands, including designing Sesame Street: Elmo’s Musical Monsterpiece for Nintendo Wii and DS. I specialize in educational games, especially for preschool and early elementary kids, and I’ve gamed everything from ABCs and 123s to dog-breeding-genetics and career education. These games are invariably nonviolent. Yet not infrequently, people lump all games into a single pool; even nonviolent games are suspect because they are considered a gateway drug, based on conversations I’ve had recently. Folks want to point a finger, and I’ve become their dumping ground for all that’s wrong in the world of children, violence, and games. They say things like:

Game developers should stop marketing to vulnerable audiences.

Parents should take more responsibility for what their children play.

Stores should more carefully monitor who they sell product to.

Politicians should levy more policies and ratings systems.

Researchers should produce more longitudinal effects study that clearly explore the nuances of games and violence.

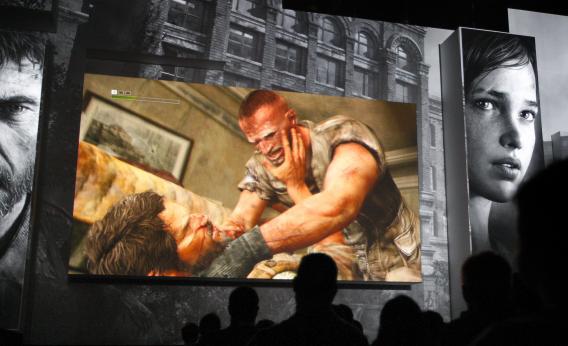

Bafflingly, these folks come to me expecting to find a sympathetic ear. Yes, I’m a victim of gun violence and do not wish that experience on anyone. But I also haven’t spent the last 13-plus years making games in a plot to destroy the industry from within. It’s insanely unproductive to lump all games together into one large pool of evil. (When has scapegoating any medium really resulted in any constructive change?) The games industry, like all media industries, has a wide range of genres—from educational to violent, cooperative to pornographic—and just as every pot has a lid, every genre has an audience, even if it doesn’t happen to be you. Personally, I play a wide variety of titles, from casual puzzlers to hardcore first-person shooters. Plants vs. Zombies designed an amazing achievements system. Left 4 Dead is another favorite, so much so that it headlined my SxSW Interactive talk in 2012. It’s a multiplayer, cooperative, zombie, apocalyptic first-person-shooter. Definitely not kid-friendly, but the cooperative game design is amazing.

Like a great independent film or a top-rated dinner, there is talent, innovation, and art behind these games. The extraordinary ones should be celebrated, studied, and taught. That’s not to say that anyone should play video games for eight hours a day, be it Sesame Street or Left 4 Dead. Nor should someone play a mature-themed game when they are not ready cognitively, physically, emotionally, or socially. But if a game designer wants to make something violent, then he should be able to do so, providing he does so responsibly. Simply telling the industry to make a sincere effort to be responsible isn’t enough to make change, nor will a broad-sweeping ban be effective. Research linking video games and violence is controversial and shaky at best, but that hasn’t, and won’t, stop people from demonizing video games. Video game developers need to change their own perspectives, not just be defensive.

One frequently referenced “cure-all” is the idea of a ratings board, similar to that of movies. The Entertainment Software Rating Board is a self-regulatory body providing ratings for games. Recent reports indicate that 85 percent of parents understand the system, which includes Early Childhood, Everyone, 10+, Teen, Mature, and Adult-Only ratings. ESRB ratings are most commonly seen on console games, such as those for Xbox 360 or Nintendo Wii, but ESRB also provides service for mobile apps. The problem is that there’s no motivation or incentive for mobile developers to submit their apps for rating. Anecdotally, I can’t remember seeing a children’s app (or any app) with an ESRB rating of lately. Clearly that’s an area for improvement, especially since parents understand the ratings system.

Beyond ratings, game developers must discard the idea that their sole responsibility is to ship the game and stop saying that it’s too hard or too expensive to do the right thing. And they must accept that it is not solely the seller’s job, be it Amazon, GameStop, or Walmart, to be gatekeeper, nor is it only up to parents to purchase the right game. Pointing fingers doesn’t solve this problem.

Game companies have many opportunities to explain the unusual strengths or educational extensions of their products with outreach materials to caregivers, schools, or social change institutions. For example, Bungie used to publish heat maps for certain statistics in Halo, providing an amazing opportunity to use data to strategize. That’s an important scientific skill. Valve, the brains behind the Steam platform and the games Left 4 Dead and Portal, are supporting teachers who wish to use Portal in the schools. (Portal is a “first-person puzzle-platformer” in which you use a gun-like tool to shoot inter-spatial portals that teleport you to other locations in the level. The goal is to put the portals in the right place so that you can teleport to the end location. It’s geeky, mind-bending, and wonderful. Teachers love it for the engineering and critical-thinking challenge.)

Game development studios that profit from bloody games could also employ strategies to offset their violence footprints. Perhaps they might encourage employees to step outside their normal game genres to make a social impact game once and a while, perhaps for an organization that promotes change. Game jams, in which game designers and developers get together for a brief period of time—often 48 hours or less—to create a game from scratch, are one such opportunity to foster this culture of social good without sacrificing extensive precious studio development time.

Similarly, development studio employees also need to be empowered to make a difference, even when they’re not in a management position. Participate in independent game jams to make games for social good, find a role locally or nationally to support policymakers, or volunteer to teach game design at a youth organization.

It’s not simply research or policy that will impact gun control and issues related to media consumption and violence. It’s the actions we take at a corporate and individual level—whether we are game developers, employees, parents, educators, or shopkeepers, or any other member of the community. When someone tries to point a finger in conversation with me, I challenge in return that they discover how they can also make an impact, long before that moment of extreme, unconscionable violence.