Last year, a startup called Planetary Resources backed by a bunch of billionaires announced plans to send robotic ships into outer space to mine asteroids.

Today, a startup called Deep Space Industries that is apparently not backed by any billionaires announced plans to send robotic ships into outer space to mine asteroids, refuel spacecraft and satellites, and 3-D print solar power stations to beam clean energy back to Earth.

Next year, look for a startup backed by no one at all to announce plans to cure all of humanity’s problems instantaneously and forever via robotic solar-powered 3-D printed outer-space panacea-bots.

Just kidding. But the ambition behind Deep Space Industries’ plans is striking for a company that admits it is still looking for more investors. The basic contours of its proposition:

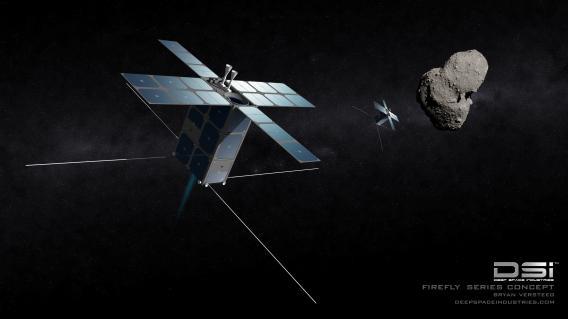

- By 2015, build a fleet of small, CubeSat-based “FireFly” spacecraft and send them on one-way, six-month-long trips to inspect small asteroids up-close

- By 2016, begin launching slightly larger “DragonFly” craft on two- to four-year trips to capture and bring back asteroid samples

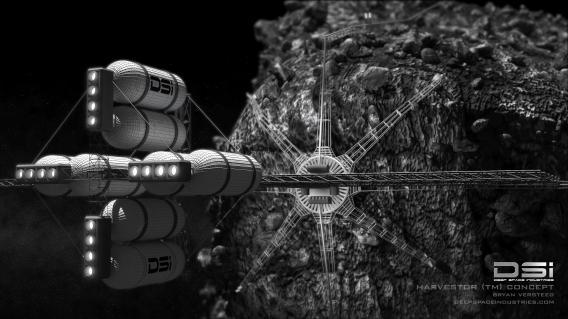

- Over time, find ways to extract precious metals and fuels from the asteroids and use them to set up the interplanetary equivalent of filling stations and foundries, refueling communications satellites and serving NASA, SpaceX, and anyone else who might happen by

- Oh yeah, and eventually build those awesome-sounding solar power stations

The shorter version: There’s gold in them thar asteroids, and Deep Space Industries wants to be in on the rush. Intrigued but skeptical, I spoke with DSI’s chief executive, David Gump, whose previous claims to fame include co-founding the space-tech company Astrobotic Technology and producing for RadioShack the first TV commercial to be shot aboard the International Space Station.

Slate: Where is the money coming from? Do you have any major investors on board?

David Gump: We have some investors, and one of the reasons we held the press conference was to let additional investors know about the opportunity. Going forward we’ll have three sources of funds: investors, customer progress payments from government customers, and payments from commercial customers.

Slate: What will you do with the asteroid samples once you’ve obtained them?

Gump: The intent is to bring several of the smaller ones back to Earth orbit where we can process them at our leisure. We have to know whether they’re solid or a loose rubble pile. That’s also important if you’re thinking in terms of planetary defense—you want to know what you’re shooting at.

Slate: How do your plans to mine asteroids differ from those of Planetary Resources? Or do you figure there’s enough room for two companies doing similar things?

Gump: It’s a very big solar system. Two companies are not going to be able to go after all the opportunities out there. As for specific plans, you’d have to ask (Planetary Resources), but they seemed to be focusing on long-distance telescope operation and discovery. We are going to go straightaway to missions that fly past [small asteroids] and missions that in the next year actually bring back samples. We’re also putting a great deal of emphasis on, “How do you turn raw asteroids into something that people want to buy?”

Slate: And how far along is this MicroGravity Foundry, the outer-space 3-D printing technology you’ve talked about? Is it in development, or more in the conceptual stage?

Gump: Well, we’ve filed for a patent and have submitted a proposal to NASA’s small business innovation research program. So it’s in the conceptual stage, but a number of parts of its process are well-known, and obviously 3-D printing is not new. What’s new is that it can work without gravity—most of the current metal processes require a gravity field. And the output is solid nickel—others use sintering, which gives you a porous structure.

Slate: What would you say to skeptics who doubt your ability to accomplish all of this given the expense and ambition of your plans and the absence of billionaire backers?

Gump: We are raising $3 million this year, and that is not a lot of money. In following years, as I said, a good portion of the cash required to get to the next level will come from customer progress payments. … I don’t believe that the scale of what we’re up to is really out of line with what is routinely done.

Slate: It sounds like you’re saying that the barriers to entry to outer space are not as high as people might think.

Gump: Exactly right. The cost of a launch is $1 to $2 million for a CubeSat, and there are plenty of components and parts available to build CubeSats from. The barriers to entry are falling, and in space that is a long-term trend. Things that used to be very expensive are now affordable.

(Bonus question: After interviewing Gump, I got the chance to ask the company’s chairman, Rick Tumlinson, whether the name “FireFly” was inspired by the cult-classic Joss Whedon TV series. Tumlinson’s response: “In fact, it was not. I’m a huge Joss Whedon fan. But it was literally, I just had this little image of this little bug flying out there into the darkness of space and then lighting the way.”)

Brian Versteeg / Deep Space Industries

This interview was edited and condensed.