Read the rest of Slate’s coverage of the Sandy Hook school shooting.

When police released the name of the man they believe shot up a Connecticut elementary school Friday morning, they unwittingly launched a million Facebook and Twitter searches. Within minutes, the Internet was dissecting the likes, photos, and tweets of young men whose name and home state matched that of the suspect.

What they found played into all of the stereotypes. Ryan Lanza is a loner. He wears a trenchcoat. He plays violent video games. He listens to heavy metal. He’s depressed. He got jilted by a girl. His Twitter handle contained a curse word. He has a misogynist streak—three days ago he tweeted, “amber’s a bitch slut.” He was deeply depressed, tweeting recently, “I would actually love if the world ended in 2 weeks.” Perhaps most chillingly, on the morning of the shooting, he tweeted, “game day fellas.”

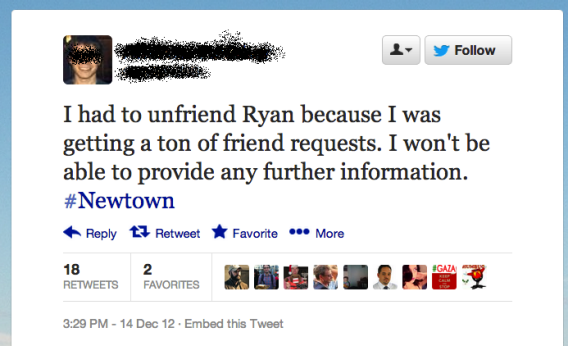

But wait! Stop the virtual presses! That was at least two different Ryan Lanzas. And within minutes, both had begun furiously asserting their innocence. Here was a Ryan Lanza on Facebook saying it wasn’t him. Here was a Ryan Lanza on Twitter saying it wasn’t him. Here was someone else on Facebook saying the shooter’s name wasn’t even Ryan Lanza. Ryan Lanzas all over the place were becoming instant celebrity-villains and getting inundated with hateful comments from people they’d never met. Their Twitter follower counts multiplied even as their actual friends de-friended and unfollowed them because they were being flooded with media inquiries. At least one innocent Ryan Lanza had his face shown on national TV in connection with the killing. (Full disclosure: Slate also tweeted a link to a Ryan Lanza Facebook page, then retracted it shortly afterward.) And to what end?

Here is what we know for sure: Someone shot up an elementary school on Friday. Many people—many children—are dead. That should give us all plenty to think, talk, cry, argue, and tweet about until we have more credible information about the perpetrator, who, it turns out, wasn’t even named Ryan Lanza.

But human nature is to want to know whom and what to blame, right now, so we can make sense of what has transpired and file it into neat boxes in our brain. And Facebook and Twitter have taught us that we are all citizen journalists, all investigative reporters, all freelance sleuths. So we cannot stop ourselves from using the tools at our fingertips—Google, Facebook, Twitter, et al.—to try to learn more.

And that’s OK. But it sure would be nice if the people using those tools—and I’m including the media along with the amateur gumshoes here—would take a moment to reflect on those tools’ limitations before spreading misinformation. Being a detective isn’t just about finding things out. It’s about knowing that not everything you find out in the course of an investigation will turn out to be true.

Crowd-sourced reporting via social media can be invaluable, particularly in situations like the Arab Spring, the Haiti earthquake, or Hurricane Sandy, in which critical, actionable information about what’s going on is widely distributed among the populace. But as we also saw in the immediate aftermath of the Aurora shooting, we tend to expect too much of the Internet when it comes to quickly pinpointing the identity and motives of the perpetrators of crimes. In those cases, information is usually concentrated in the hands of a few, and most of them are already busy talking to authorities. Nice as it would be to have immediate answers, jumping to the wrong conclusion only compounds the damage. The truth may be out there, but it’s not always just a click away.