According to law enforcement agencies, the rising popularity of Internet chat services like Skype has made it difficult to eavesdrop on suspects’ communications. But now a California businessman is weighing in with what he claims is a revolutionary solution—a next-generation surveillance technology designed to covertly intercept online chats and video calls in real time.

Voice over IP chat software allows people to make phone calls over the Internet by converting analog audio signals into digital data packets. Because of the way the packets are sent over the Web, sometimes by a “peer-to-peer” connection, it can be complex and costly for law enforcement agencies to listen in on them. This has previously led some countries, like Ethiopia and Oman, to block VoIP services on “security” grounds. In the United States and Europe, too, VoIP has given authorities a headache. The FBI calls it the “going dark problem” and is pushing for new powers to force internet chat providers to build in secret backdoors to wiretap suspected criminals’ online communications.

In response, technology companies have rushed to develop new surveillance solutions. Dennis Chang, president of Sun Valley-based VOIP-Pal, obtained a series of patents related to online voice calls earlier this year. Among them is a “legal intercept” technology that Chang says “would allow government agencies to ‘silently record’ VoIP communications.”

With this technology, suspects whom authorities wanted to monitor could be identified through their username and subscriber data. They could also be found, according to the patent, by billing records that associate names and addresses with usernames, making not only calls but “any other data streams such as pure data and/or video or multimedia data” available for interception. Of course, savvy criminals—or citizens worried about privacy intrusions—could probably find a way to circumvent identification by using false subscriber data and by masking their IP address with anonymity tools. But the point is that Chang’s patent would make it much easier than it is currently for authorities to monitor VoIP calls, by fundamentally restructuring the basic architecture of how the calls themselves are routed over the Internet.

Governments across the world are concerned about how the Web is impacting their ability to conduct surveillance. As “4G” mobile phone networks make it easier than ever to make cheap or free VoIP calls almost anywhere and anytime, the number of mobile VoIP subscribers is predicted to reach 410 million by 2015. This has led to a number of international plans that would compel VoIP chat providers to comply with “lawful intercept” requests. In turn, a battle to capitalize on lucrative next-generation surveillance technology seems to be taking place.

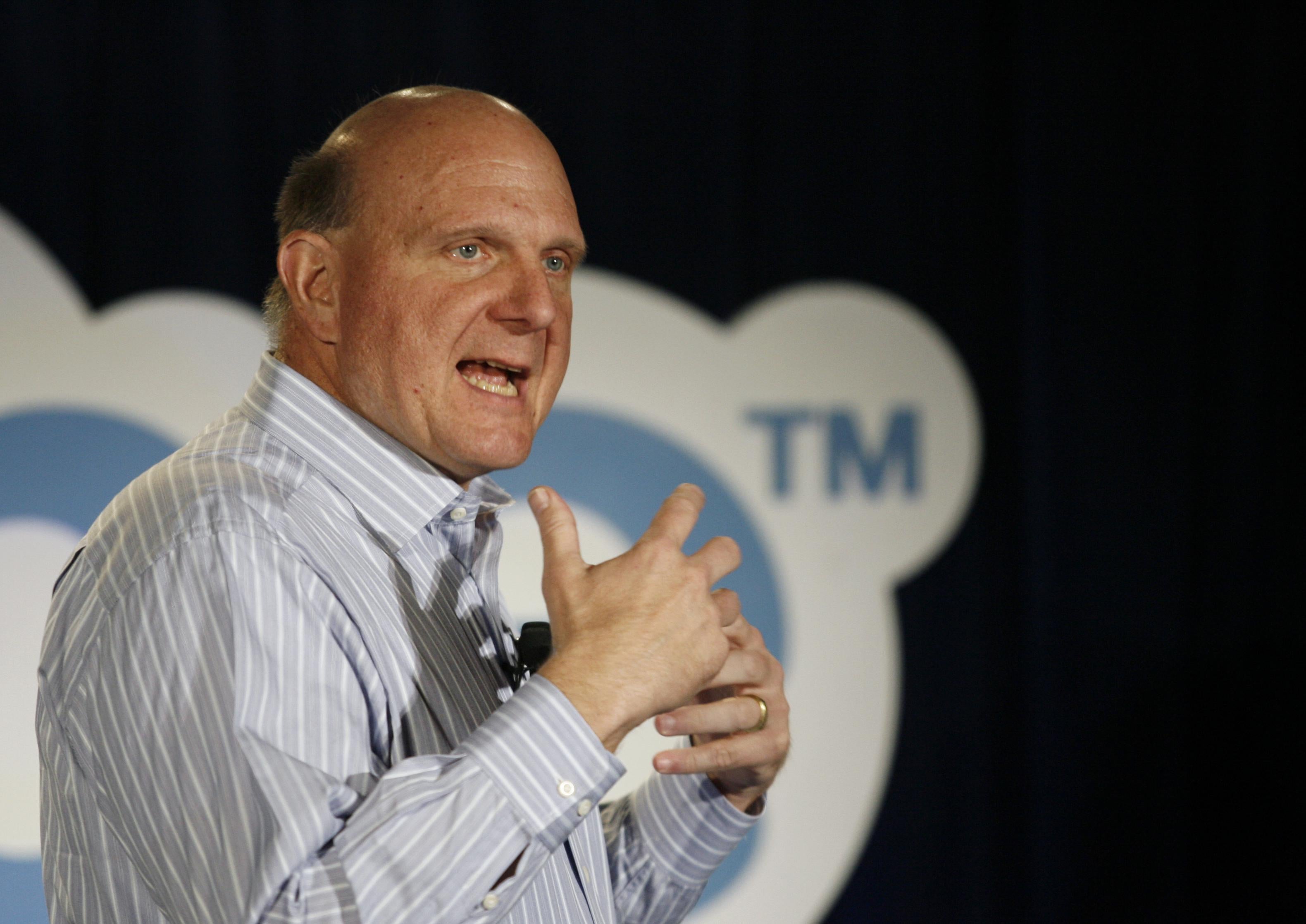

Chang, a former IBM employee, could be setting himself up for a clash with Microsoft. His patent was originally filed back in 2007—two years before a similar Microsoft patent was filed for “legal intercept” technology designed to be used with VoIP services like Skype to “silently copy communication transmitted via the communication session.” (Because Microsoft acquired Skype last year, questions have been raised about whether the patent is part of a plan to build intercept capabilities into the popular chat service, though Skype has not yet commented on the matter.) A press release issued by Chang’s company earlier this month noted that VoIP-Pal had identified “substantial similarities” between its patent and Microsoft’s. Was Chang trying to insinuate that Microsoft had copied his patent? I sent him a series of questions by email, but he responded that the company was “not in a position to make any statements” at this time.

Either way, the race to wiretap the Web is heating up. Aside from companies competing over patents, civil liberties and privacy concerns due to increasing levels of surveillance have sparked huge interest in new encrypted communications platforms, deliberately designed to shield users from potential monitoring. So even if governments were able to successfully implement VoIP-Pal’s lawful intercept technology on a countrywide scale, they should expect their would-be targets to find new ways to circumvent surveillance.