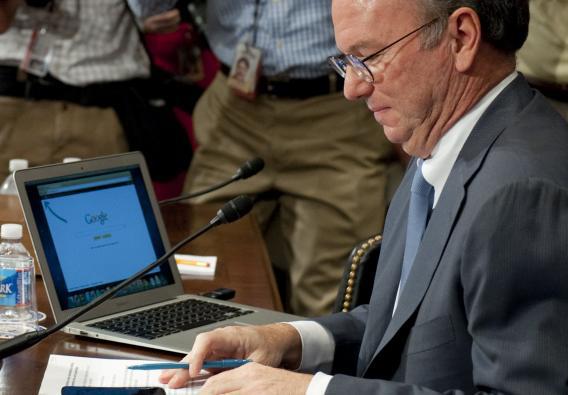

Belatedly following the lead of Mozilla’s Firefox, Microsoft’s Internet Explorer, and Apple’s Safari, Google is adding a “Do Not Track” option to its increasingly popular Chrome browser, AllThingsD reports. That means future updates of the browser will allow users to tell websites that they don’t want to be tracked.

The move makes good on Google’s February pledge to support the option by year’s end in response to an online privacy push by the White House, among others. It also puts Google in a bit of a funny position. The company, which reaps billions each year from targeted advertisements that rely on tracking users, was not only the last major holdout on the Do Not Track initiative. In at least one high-profile case, it actually subverted Safari’s default privacy settings (a move for which the FTC made it pay not-so-dearly last month).

Lately rivals have tried to exploit Google’s position by beefing up their own privacy efforts. Mozilla touts Firefox by pointing to its own not-for-profit status, and Microsoft’s latest edition of Internet Explorer tweaks Google by making “Do Not Track” the default option.

Google—and many, many other websites that depend on advertising for revenue—would hate to see that become the norm. So why is Mountain View embracing Do Not Track at all?

Possibly because it legitimately cares about not being evil and giving its users control over their data, sure. More importantly, though, Google recognizes that Do Not Track is far from the worst-case scenario. For one thing, it’s better for Google than watching Chrome users flee for the shelter of Mozilla or Apple, let alone Microsoft. And as a voluntary, industry-led initiative, it is far better than being forced to comply with some sweeping new federal privacy bill. Do Not Track doesn’t actually require websites to do anything differently. All it does is send them a message letting them know when a visitor to their page has the option selected on her browser. How to respond is up to the website, though industry groups are working to agree on (voluntary) standards.

Christopher Wolf, a top privacy attorney and co-chair of the nonprofit Future of Privacy Forum, tells me Google’s participation in Do Not Track will lend the initiative more credibility in Washington. “It should diminish the drumbeat for specific legislation addressing the online tracking issue.”

Finally, it gives Google a better seat at the table as the Internet figures out how exactly to deal with Do Not Track requests. All in all, it’s Google’s best chance to have its don’t-be-evil cake and eat it too.