An email claiming to reveal a political scandal will grab the attention of almost any journalist. But what if the email was just a ruse to make you download government-grade spyware designed to take total control of your computer? It could happen—as a team of award-winning Moroccan reporters recently found out.

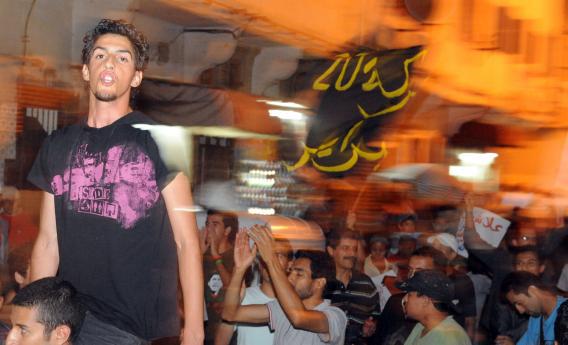

Mamfakinch.com is a citizen media project that grew out of the Arab Spring in early 2011. The popular website is critical of Morocco’s frequently draconian government, and last month won an award from Google and the website Global Voices for its efforts “to defend and promote freedom of speech rights on the internet.” Eleven days after that recognition, however, Mamfakinch’s journalists received an email that was not exactly designed to congratulate them for their work.

The email, sent via the contact form on Mamfakinch.com, was titled “Dénonciation” (denunciation). It contained a link to what appeared to be a Microsoft Word document labeled “scandale (2).doc” alongside a single line of text in French, which translates as: “Please do not mention my name or anything else, I don’t want any problems.” Some members of the website’s team, presumably thinking they’d just been sent a major scoop, tried to open the file. After they did so, however, they suspected their computers had become infected with something nasty. Mamfakinch co-founder Hisham Almiraat told me that they had to take “drastic measures” to clean their computers, before they passed on the file to security experts to analyze.

What the experts believe they found was, they said, “very advanced”—something out of the ordinary. The scandale (2).doc file was a fake, disguising a separate, hidden file that was designed to download a Trojan that could secretly take screenshots, intercept e-mail, record Skype chats, and covertly capture data using a computer’s microphone and webcam, all while bypassing virus detection. Christened a variety of names by researchers, like “Crisis,” and “Morcut,” the spy tool would first detect which operating system the targeted computer was running, before attempting to infect it with either a Mac or Windows version.

Once installed, the Trojan tried to connect to an IP address that was traced to a U.S. hosting company, Linode, which provides “virtual private servers” that host files but help mask their origin. Linode says using its servers for such purposes violate its terms of service, and confirmed the IP address in question was no longer active. The use of Linode was a clear attempt to make the Trojan hard to track, according to Lysa Myers, a malware researcher who analyzed it.

But there were a couple of clues. The Trojan’s code repeatedly referenced the acronym “RCS” alongside occasional mentions of the Italian name “Guido.” This pointed straight to an Italian company called Hacking Team, one of the leading providers of spyware-style tools to governments and law enforcement agencies worldwide.

Hacking Team’s flagship product is called “Remote Control Systems,” a Trojan it describes as “eavesdropping software which hides itself inside the target devices.” RCS can spy on Skype chats, log keystrokes, take webcam snapshots—identical to the Trojan used to target the Moroccans. It can also be tailored to infect a computer via “opening a document file,” according to marketing materials, and “can monitor from a few and up to hundreds of thousands of targets.”

Hacking Team did not respond to repeated requests by phone and email for comment. Notably, however, during an interview last October the company’s co-founder David Vincenzetti told me that RCS had since 2004 been sold “to approximately 50 clients in 30 countries on all five continents.” (Most people today consider there to be seven continents—Africa, Antarctica, Asia, Australia/Oceania, Europe, North America, and South America—but in parts of Europe it used to be taught that there were only five: Africa, America, Asia, Australia, and Europe.) So while it’s not possible to say for sure whether Moroccan authorities are using RCS, it’s certainly being deployed by countries in that region of the world, by Vincenzetti’s own admission.

The Moroccan case is not isolated, and it’s likely we’ll hear more about such attacks in the future. Last month, as I reported for Future Tense, a number of Bahraini activists were targeted with a Trojan tool purportedly designed by a British spy tech company, Gamma Group, which is one of Hacking Team’s main competitors. Human rights organizations have been concerned for some time about Western companies selling high-tech surveillance equipment to countries in which it may be abused. Ever mounting evidence of the equipment being used to target pro-democracy activists and journalists could have repercussions for the companies involved and is likely to strengthen the case for stricter export controls.

Thanks to Jean-Marc Manach for help with the French translation.