Among the unintended offspring of new technologies are the goons that arrive to taunt early adopters. This month Steve Mann, a computer engineering professor at the University of Toronto, was attacked for wearing an augmented vision device he’d developed called an EyeTap. Like Google’s Project Glass, the EyeTap is part of an ongoing experiment with computer-mediated reality. As Mann’s ordeal suggests, its relationship with real-reality is also a work in progress.

While on vacation in Paris in early July, Mann and his family were sitting down to eat McDonald’s when three men (likely McDonald’s employees) tried to remove the device from his head—unsuccessfully, because, as Mann writes in his blog, the EyeTap cannot be detached from the wearer’s skull “without special tools.” The men then ripped up the professor’s documentation for the vision system, including a letter from his doctor, and pushed him outside. Mann was unhurt, but his device was broken.

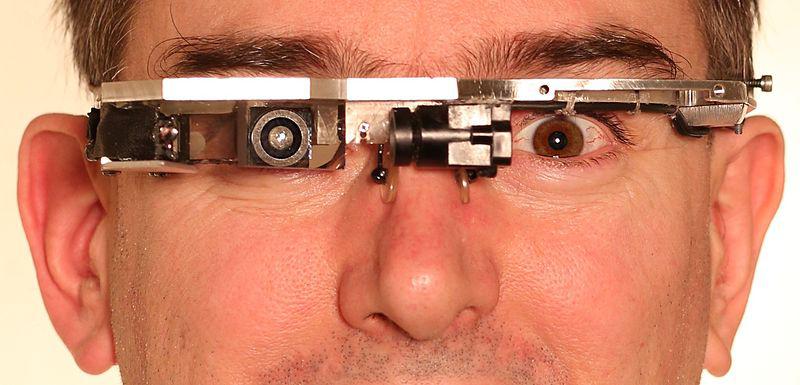

The EyeTap, as Mann explains in a research paper, is a “digital eye glass” that makes the eye into “both a display and a camera.” Computer data stream from its lens onto the user’s retina. At the same time, the gadget processes what the wearer is seeing and allows him to alter his visual perceptions, augmenting and diminishing details at will. For instance, a wearer might issue a command to magnify, say, a menu on the wall of a fast-food restaurant. (That is, if one hasn’t already boycotted that fast-food restaurant, as Techcrunch urged readers to do to McDonald’s Monday).

After the incident, Mann was able to retrieve stored and unprocessed images from his battered device to obtain snapshots of his alleged assailants. (You can check them out here).

Some have called the events in Paris the “world’s first cybernetic hate crime.” The billing may be a little extreme: After all, Mann fastened the EyeTap to his head for research purposes, not because he suffered from any visual impairment. Over at Forbes, Andy Greenberg questions whether the McDonald’s employees were actually spooked because they thought Mann might use his digital eye glass as a recording device, in violation of restaurant policy. (Greenberg nicely draws out the tangle of privacy issues that might accompany a trend of inconspicuous wearable cameras.)

Of course, Mann’s problem in this instance was that his wearable computing system didn’t prove inconspicuous enough. And if the Paris assault occurred because a bunch of thugs found the EyeTap funny-looking, their intolerance deserves the Internet fire it’s drawn. Mann, after all, has written that he developed the technology in order to “help people see better.” (He says that he’s also designed visual enhancement systems for the blind and partially sighted.) His experience at McDonald’s doesn’t bode well for those looking into augmented reality as one answer to a visual handicap—a circumstance that would blur the line between a reprehensible case of bullying and an even more reprehensible hate crime.

McDonald’s told Forbes that it “[takes] the claims and feedback of our customers very seriously. We are in the process of gathering information about this situation and we ask for patience until all of the facts are known.”