Iran has become the next big star of in video game world—even if it’s just in terms of creating jaw-dropping headlines. In recent months we’ve seen gaming-related charges of espionage and a death sentence. There have even been virtual fatwas.

These are the side effects of the Iranian video game industry’s rapid growth—something that Ayatollah Seyed Ali Khamenei himself has apparently pushed for.

“We developed around 140 games with Islamic and Iranian contents which can compete with foreign products,” said Mokhber Dezfouli, secretary of Iran’s Secretary of the Supreme Council of Cultural Revolution, in a recent interview with the Fars News Agency, which Reuters calls “semi-official” for its ties to the government. Iran even has a National Foundation of Computer Games and its own version of E3, the United States’ largest annual video game conference.

So what is behind this state-funded push to establish an Iranian video game industry? Well—it’s certainly not the desire to create art.

In the New York Times last week, Nicholas Kristof pointed out that Iran is a young nation (about half the population is under 25), and education levels are rising. He recalled witnessing many Iranians indulging in traditionally Western pleasures: amusement parks, pirated music, drugs, and “Grand Theft Auto.”

“This youth culture of Iran is nurtured by the Internet—two-thirds of Iranian households have computers—and by satellite television, which is banned,” writes Kristof. Iran is also not subject to WTO copyright laws, making piracy widespread and thus newly released games easily available. And according to the Guardian, “Iranian authorities have complained in recent years that ‘enemies’ have targeted their country in a ‘soft and cultural war’ using illegal satellite channels, western novels, Hollywood films and computer games.” All of this has prompted Iran to create its own popular-entertainment industry and heavily filtered “halal” Internet.

Back in December, Iran banned the sale of the game Battlefield 3, taking issue with its depiction of a U.S. assault on Tehran. The NFCG responded by announcing its plans to create a game called “Attack on Tel Aviv,” which features “Iran’s reaction toward depicting an American soldier on Tehran’s streets in ‘Battlefield 3,” according to the Tehran Times.

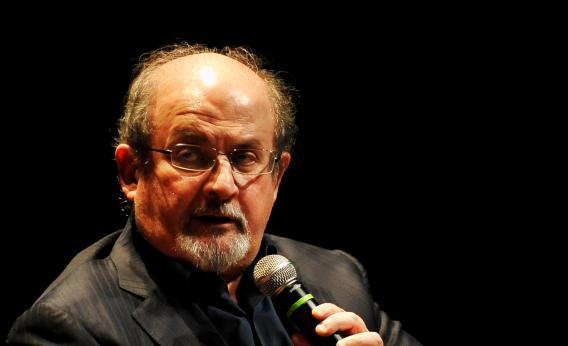

More recently, a game with the remarkable name “The Stressful Life of Salman Rushdie and Implementation of His Verdict” was announced at the second annual Computer Games Expo in Tehran. The Guardian says it is being developed by the government-funded Islamic Association of Students, which hopes to educate a younger generation of the fatwa placed on The Satanic Verses author Salman Rushdie by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in 1989. While details on the game’s actual contents have yet to be released, Time speculates that the title suggests players may be tasked with answering the “23-year-old call for the author’s head.”

The video game politics don’t stop there. In an interview with Kotaku on Monday, Iranian/Canadian game developer Navid Khonsari revealed he has been branded a spy for his latest game, which depicts the chaos of the 1979 Iranian Revolution. As a result, he can no longer return to his home country.

Khonsari’s woes pale in comparison to those of Amir Hekmati. Arrested and accused of espionage late last year for his alleged involvement in designing CIA-funded games, the former U.S. Marine was sentenced to death in early January.

In a controversial confession on Iranian state television, Hekmati claimed his company, New York’s Kuma Reality Games, was developing titles aimed at “manipulating public opinion in the Middle East,” according to Kotaku. However, a follow-up article revealed that Kuma’s government funding was for a language education game for the Department of Defense.

While Hekmati’s death sentence was overturned in March, he remains imprisoned in Iran.