It is a bit scary waking up to the news that someone has decided to become you—or at least use your visage on Twitter.

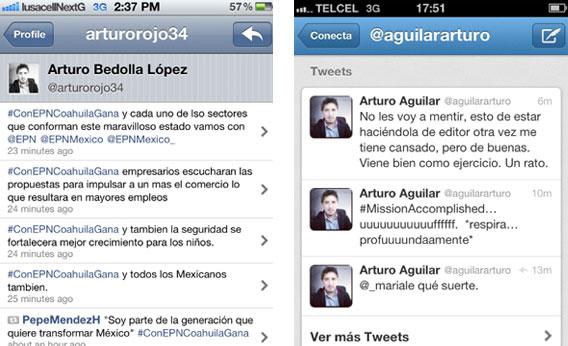

Recently, it happened to a friend of mine named Arturo. He didn’t know about his social-media doppelganger until he received a DM with a Twitter handle he couldn’t recognize. He opened the link and … surprise! It is him. To be precise: It is his photograph, but the account belongs to someone else who is spreading political propaganda in favor of Enrique Peña Nieto, the PRI’s candidate in the Mexican presidential election. As Arturo, a university professor and journalist, wrote in Animal Politico, the Mexican news site that I work for: “in words of Marlon Brando in Apocalypse Now: The horror. The horror.”

Arturo—or rather, Arturo’s avatar—had became part of the army of spambots invading social networks ahead of the Mexican presidential election. They constantly tweet the same message—trashing or praising a particular candidate—trying to make it to the top 10 trending topics, thereby getting everybody’s attention.

screenshot from Twitter.

Politicians from all parties deny any connection to the spambots, claiming that these ghosts are “digital activists” who decided on their own to promote a candidate. The truth is that they are the product of expensive and rather ineffective social media campaigns built on the hypothesis that discussions in Twitter will somehow transcend cyberspace and influence the voter’s decisions (much the way it did with Obama’s campaign in 2008 or in South Korea’s election in 2011).

The Mexican presidential election has seen the rise of several groups of “spambot hunters” aiming to expose these politicians and save the digital space from the disturbing noise produced by political bots. How many bots have these “digital crusaders” caught so far? Thousands. Literally. They have documented bots from all parties, but mainly from the PRI, the party that ruled Mexico for 71 years and whose presidential candidate is currently leading the polls. Just follow #CazaUnBot (which translates into #HuntaBot) on Twitter and you will see the evidence. You can also visit their tumblr here.

As Arturo soon found out, regaining control of your personal image once it’s out on the Web is not easy. In fact, according to Twitter, there is nothing one can do but wait until these people decide that they are tired of using your avatar for digital warfare. In reply to Arturo’s complaint, Twitter said it only reviews “avatar and background images for violations such as nudity or pornographic content. … Users are allowed to use their twitter accounts for a variety of purposes, including for parody, commentary, or other informational uses.”

Are these spambots going to influence the elections? It’s highly unlikely. They are not and will not become “influencers” in any sort of way: They don’t engage in conversation, promote debate, or send relevant information of any kind. They’ve few or no followers. They’re just annoying—and expensive—noise producers. Yet, they’ve managed to raise some interesting questions on the future of digital activism and the political use (and abuse) of Web-based propaganda.