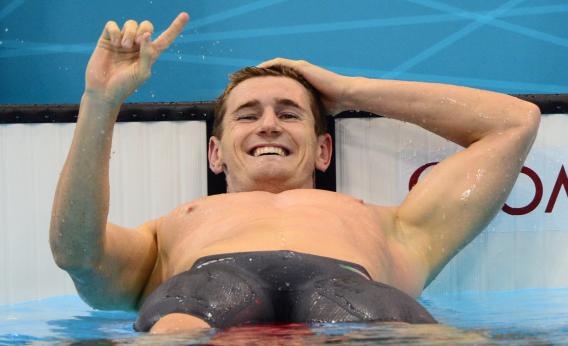

It’s Tuesday, so another Olympian must have done something illegal. South African swimmer Cameron van der Burgh has admitted that he cheated in winning the 100-meter breaststroke last week. What was van der Burgh’s performance enhancer? Illegal “dolphin kicks.”

“Everybody does it—well, if not everybody, 99 percent of them,” van der Burgh told the Sydney Morning Herald, explaining his rationale for taking more than the one dolphin kick that’s permissible under the rules of the breaststroke. “If you’re not doing it you are falling behind and giving yourself a disadvantage.” What is a dolphin kick exactly, and why are swimming’s powers that be so eager to limit its use?

The dolphin kick, also known as the butterfly kick, dates back to 1935. Its originator was a collegiate swimmer named Jack Sieg, a transfer student from the University of the Ocean who came to terra firma to introduce us to his people’s amphibious ways. If you’ve ever seen an episode of Flipper, you know that dolphins propel themselves through the water by flapping their tails up and down. A dolphin kick mimics this movement.

Today, the dolphin kick is the fastest kick in competitive swimming. (It is much, much faster than the “manatee kick,” in which swimmers float cow-like in the water and try to avoid being hit by a jet ski.) It is most notably used at the start and off of turns, when swimmers, completely submerged, use the kick to propel themselves through the water faster than if they were swimming on the surface. As this 2008 Popular Science article explains, swimmers can move faster underwater because there’s less resistance down there.

In 1988, an American backstroker named David Berkoff brought the dolphin kick into the big time when he used it to win four medals at the Seoul Olympics. “It seemed pretty obvious to me that kicking underwater seemed to be a lot faster than swimming on the surface,” Berkoff told NPR in 2008. At Seoul, Berkoff used the kick to stay underwater for great lengths of time, giving him an advantage over his surface-swimming competitors. Commentators called it the “Berkoff Blast.” FINA, the sport’s international governing body, called it unacceptable.

In 1989, FINA ruled that competitive backstrokers could spend no more than 10 meters per lap underwater. (The limit was later raised to 15 meters per lap.) In 1998, FINA put the same restrictions on butterfly and freestyle races. Today, the lane lines in every competitive pool are marked at the 15-meter line, so that the swimmer knows when to emerge from the bottom of the sea.

This killed the Berkoff Blast, but it didn’t kill the dolphin kick. Since 1988, it has been used in every Olympics, not always legally. At the 2004 Olympics, for instance, underwater footage revealed—as it did in the case of van der Burgh—that Japanese swimmer Kosuke Kitajima used an illegal dolphin kick while winning gold in the 100-meter breaststroke. But officials did not look at that underwater footage, either in 2004 or at the London Olympics. Instead, they rely on their eyes, staring into the water in search of potential kick-related infractions. If the dolphin detectors don’t see anything at the time, the race is not subject to review. And they very, very rarely see anything.

Back in 2004, the dolphin kick was completely illegal in breaststroke races. After the Kitajima controversy, FINA strangely decided to become more permissive, ruling that breaststrokers could take one—and only one—dolphin kick at the start and the turn of each race. But according to Cameron van den Burgh, swimmers are still using multiple kicks.

It’s hard to blame the swimmers for dolphin-kicking up a storm. As with any other performance enhancer, the idea that the guy in the next lane is cheating exerts pressure to do it yourself, lest you drop out of medal contention. And it’s hard to blame FINA for putting some limits on the kick. Swimming’s governing body wants people to do the stroke they’re supposed to be doing. If you’re swimming the breaststroke, FINA wants you to kick like a frog, not a dolphin. Otherwise, what’s the point?

But what’s strange about this whole situation is that FINA could police the kick if it wanted to. The underwater cameras that NBC used throughout the Olympics could easily detect illegal kicks, allowing judges to disqualify scofflaws immediately. So why doesn’t FINA use the swimming equivalent of the replay booth? Probably because it’s less controversial to let swimmers get away with Flipper-izing than it is to kick someone out of an Olympic final. And maybe FINA also realizes that stricter guidelines would slow down times, reducing the volume of attention-getting world records.

Any other theories? Send me an email or leave your thoughts in the comments.