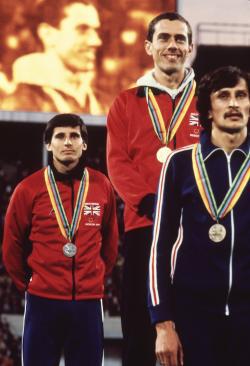

On Friday, Cuban shooter Leuris Pupo took gold in the Olympics’$2 25-meter rapid fire pistol event. In the photo above, silver medalist Vijay Kumar stands on the left and bronze winner Ding Feng is on the right. Though Pupo can look down at both his vanquished foes, Kumar stands at the same level as the man he beat out for second place.

Photo by AFP/AFP/Getty Images.

Why don’t silver medalists—who ran faster, jumped higher, threw further—get to tower over third-place finishers? Because the International Olympic Committee doesn’t allow it. The designers of London 2012’s purple podiums, a group that calls itself The Kims of Design, told me via email that parity between the silver and bronze platforms was mandated by the IOC.

There is a long history of silver and bronze medalists looking each other in the eye at the Olympics. The 1932 Lake Placid Games started the tradition, when then-IOC president Count Henri de Baillet-Latour stated that the Winter Olymics’ bi-level podium design “worked very well that way.”

The 1932 Los Angeles Games featured a central podium in Memorial Coliseum in which the gold-medal winner stood alone at the top, with the silver and bronze medalists at the same height below. It was the same story at Berlin 1936. After the two World Wars canceled the next two Olympics, did anything change when the games came back to London in 1948? No, it did not. It was the same story at the Summer Games in 1952, 1956, 1960, 1964, 1968, 1972, and 1976.

Photo by STAFF/AFP/Getty Images.

Prospects for podium reform wouldn’t seem too great at the 1980 Moscow Games, which were boycotted by the United States. Though a Communist nation would seem an unlikely candidate to place athletes in different strata, the Soviets’ Summer Games did indeed make the move to vertically differentiate bronze and silver. And the height change stuck at the Communist-organized 1984 Sarajevo Winter Games, which featured a lovely overlapping podium design.

How would the United States respond at the 1984 Summer Games in Los Angeles? By going back to the old-style, flat-bottomed podium. This has remained the law of the Olympics land ever since, with a couple of exceptions. This photo from the women’s team all-around gymnastics medal ceremony in Seoul suggests there may have been some limited tri-leveled podium usage in 1988. And the final bright spot for fans of the three-tiered podium came at the 1994 Winter Games in Lillehammer. (For podium completists, here are images of the medal stands from the Summer and Winter Games in 1992—Albertville and Barcelona—1996, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010, and London 2012.)

It is time for us to abandon this tradition of unearned equality. The European Gymnastics Championships can get it right. Minor Korean marathons, the World Equestrian Games, international college curling competitions, and British youth gymnastics clubs can all put the second- and third-place finishers at the right height. Even Olympic test events can nail it. It’s time for the Olympics to do the same and finally live up to the middle part of that famous motto: “Faster, Higher, Stronger.”