Figuring out the winner of an Olympic sporting event usually doesn’t require a lot of thought. Winners swim faster, jump further, and lift more than everyone else. That’s why I find the Olympic sports with judged artistic elements so frustrating. Why can’t the gymnast who does the most flips win?

Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympic Games, would call me a fool. At de Coubertin’s urging, the Olympic Games featured art competitions between 1912 and 1948. Though the categories varied and medals were not always awarded, gold, silver, and bronze were handed out during most of these years to the best in literature, painting, scupture, architecture, and music composition.

According to The Forgotten Olympic Art Competitions by historian Richard Stanton, de Coubertin viewed the Olympics as a model school system that, like the ancient Olympics, should “embrace the entire known world.” Once the International Olympic Committee got the games up and running in 1896, he pushed the IOC to incorporate art competitions. This was not a popular idea, especially among artists. Before the 1912 Games in Stockholm—the first to feature competitive art—the Swedish Society of Arts declared that an art competition had no purpose; art was to be created for art’s sake. The Swedish Royal Academy agreed, reasonably suggesting an art exhibit accompany the games instead.

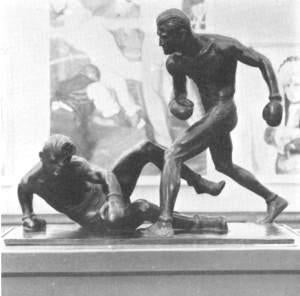

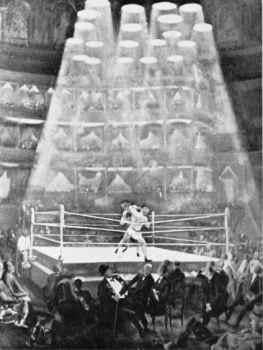

Courtesy the Olympic Games Museum.

But de Coubertin, who was the president of the IOC at the time, was resolute. He demanded that art contests be held alongside sporting events, and so they were. From the start, the contests were plagued with problems. The judging was suspect: The first gold medal in literature went to a pseudonym-disguised de Coubertin for his “Ode to Sport.” Verifying the amateur status of the competitors also proved challenging—the IOC demanded that professionals stay out of the Olympic stadium and the Olympic literary salon. More problematically, the events, which required entrants to submit a sport-themed work, failed to attract renowned artists. “If it had been the best poets of the time,” Finnish literature contestant Aale Maria Tynni reportedly said, “it would have been different.”

For the 1952 Games in Helsinki, the IOC converted the art competition to an exhibition before abandoning competitive art entirely thereafter. Even so, the seven Olympic art contests left us with several impressive records. In 1948, Tynni won a gold medal for her poem “Laurel of Hellas.” She holds the title of the only woman to ever win an Olympic gold medal in art. The same year, Britain’s 73-year-old John Copley became the oldest medalist when he won a silver medal for an etching called Polo Players. But sadly, Copley is no longer considered an Olympic medalist, as these bygone art championships have been removed from the games’ official record.