Question: How do you find the vegan at the dinner party?

Answer: Oh, don’t worry—they’ll let you know.

Get it? Because vegans are crazy demanding and annoying and prone to proselytizing.

HA.

I’m kidding, of course; I start with this dumb joke only as a kind of exorcism, because this post will be no place for food restriction-phobia. If you came here frothing with veggie-hate or seething with allergy denial, get it out of your system (perhaps with a good cleanse) right now. In this safe space, we assert that vegetarians, vegans, gluten-abjurers, religious observers, and all other members of the Community of Food Restricted Peoples (CFRP) are legitimate human beings who presumably like to be entertained as much as anyone else, and we will endeavor here to work out a model of accommodation—and compromise—functional for both guest and host alike.

However, as a person whose only notable “food preference” is against chocolate cake (no, I don’t want your recipe), but who also often cooks for members of the CFRP, I thought it best to “step-back,” as is often said in discussions of “privilege,” and consult the group for its own opinion on the matter. My Facebook network did not disappoint and, indeed, proved that FRPs are, on the whole, agreeably practical about these matters. The most common response I received to the question “What do you expect from a host?” was, basically, not very much. Many FRPs felt it was appropriate to alert the host to their particular concern at the time of invitation, but also felt that they should, as the special case, be willing to bring their own food if the host would find it a burden to change the menu. One respondent was particularly vocal about not being an imposition on his friends:

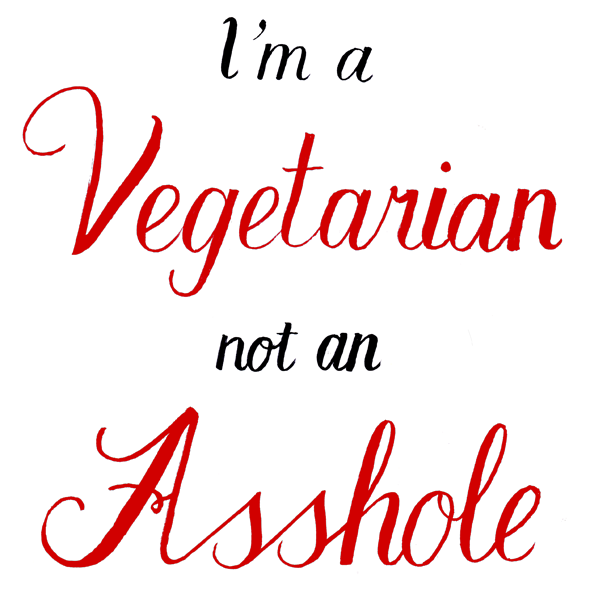

Illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker

“I tell people I’m a vegetarian, not an asshole. If you went out of your way to make something and there’s no easy alternative and I’m hungry, then I’ll smile and enjoy it. The worst thing would be to throw meat away because of my principles. Not only will I end up hungry but that animal will have been ground up literally for no reason at all … I try to keep my dietary restrictions from being a social liability.”

This “figure it out for myself” strategy seems workable to me; but then again, it does take some of the joy out of the wine-and-dine entertaining model that L.V. Anderson articulated in Rule No. 3. To be sure, as a well-intentioned host who sometimes forgets that duck fat is non-vegetarian, I appreciate this fellow’s esprit de corps. But I do think that hosts of vegetarians should try to compromise as well. In my own experience, it’s useful to have a few suitable and thoughtful recipes on hand—an individual portion of homemade Spanish pisto (even made ahead and frozen) with a poached egg on top, for example—that can be quickly added to the workflow when the need arises. In fact, with something like that on their plate, the vegetarian guest’s meal may be envied by the meat-eaters surrounding him.

Of course, vegetarianism, as well as straightforward, yes/no food allergies and religious prohibitions, really don’t pose that much difficulty for a competent host in the grand scheme of things. But what about vegans or the gluten-averse or those with other needs that place much of the standard fridge and pantry off-limits? I’ve struggled with this one, as I have friends in this category; but, since we’re talking rules, I must be plain: Vegans and similar heavily restricted folk would probably do best to bring their own food, as many of my CFRP respondents suggested. It is a lot to ask most cooks to adjust to these strictures, especially if you are not a recurring guest and you want something other than salad. Impugn my culinary imagination if you must, but I’m just being pragmatic about the time and inclination I have to learn an entirely different (and, to be frank, useless outside of your presence) mode of cooking.

Of course, as a gluten-intolerant friend pointed out, one way to avoid this unpleasantness is for the FRP to throw the dinner party herself—it should go without saying that guests should be happy to try gluten-free or vegan food in that person’s home. And who knows? Perhaps the ignorant like me will pick up a recipe or two that we can execute in the future.

In the end, it’s truly this spirit of compromise that I hope will prevail in the ongoing food restriction debates. Reasonable people can lead different dining lifestyles (whether for health, ethical, or strictly preferential reasons), and, as an ex-veggie friend eloquently put it, “not be dicks about it.” A little accommodation—on both sides—goes a long way.

But what if none is forthcoming? If a host is not willing to accommodate her guests even a little, she may want to think about why she’s entertaining: is it for her friends or, in reality, herself? If it’s the latter, there are a number of perfectly lovely cookbooks under the designation “cooking for one.” And as for those rare militant FRPs who are totally uncompromising, here are a few parting words courtesy of the Food Commander, whose entertaining wisdom I quote because I could not hope to say it better: “…kindly embrace the fact that your body is not all that fragile. Humans survive every day in conditions way worse than, say, a four-course dinner in an Upper East Side townhouse … [but] if your narcissism prevents you from relinquishing some control and sharing a communal experience or, put differently, if you cannot stomach the idea of being served the same food as everybody else, then simply avoid communal experiences altogether. You will not be missed.”