The United States debuted a redesigned $100 bill today, and it’s possibly the weirdest-looking note the Federal Reserve has ever issued. The bill features everything you love about the existing $100 bill—it is worth $100—and adds a bunch more jarring, unfamiliar features, like a blotchy orange watermark on the right-hand side, a blue 3-D security ribbon that runs down the middle, and a weird picture of a feather quill, an inkwell, and a bell. (If you hold the bill at an angle, the bell changes color.) This is probably a reference to the Declaration of Independence, but might just be a subtle advertisement for Quill brand pens. Who’s to say?

The point of this redesign, of course, is to deter counterfeiters, who have apparently not yet thrown in the towel, even though I informed them back in March that counterfeiting American currency is the dumbest crime imaginable. The new $100 note is just the latest in a series of advanced, secure bills the government has issued over the years. Here’s a brief history of how they were made—and, sometimes, how they were defeated.

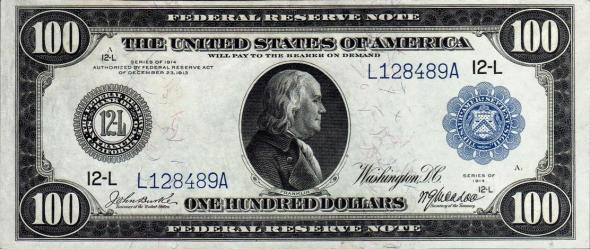

Wikimedia Commons

1914: Before 1914, America’s paper money had been issued as “United States Notes” by private banks that had been given federal charters, by small children with construction paper, and in many other formats, too. The history of American paper currency is very confusing, and this confusion was a boon to counterfeiters, who benefitted greatly from the non-standard design. The first $100 Federal Reserve Note, like some of the bills that came before it, featured some basic security features that still exist to this day: colored threads scattered across the face of the bill; intricate engraving that is difficult to duplicate; the Treasury seal and serial number rendered in ink of a different color; and special paper stock that is not commercially available.

Collectors.com

1929: The 1914 note was a step forward, but it was still possible to defeat it; antique paper money dealer Manning Garrett has noted that some 1914 $100 Federal Reserve notes are “are virtually undetectable as counterfeits.” The big security advance in 1929 was the implementation of a standard design across all denominations. This made it easier for regular people to know what money was supposed to look like, and made it harder for inept counterfeiters to claim that, yes, the $100 bill did feature a portrait of Eddie Rickenbacker, thank you very much!

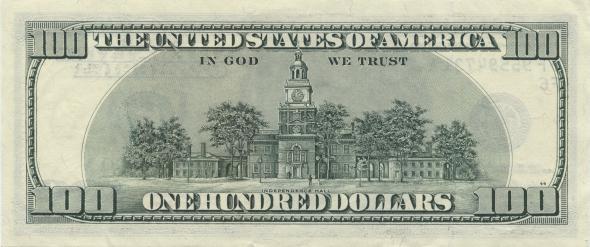

Wikimedia Commons

1966: In 1955, Congress passed a law requiring that the phrase “In God We Trust” appear on all American currency, be it coin or paper. Its inclusion on the reverse of all $100 bills from 1966 onward helped merchants realize they should probably be suspicious of bills that contained other slogans, like “The Business of America is Business,” “Better Dead than Red,” and “Ich bin ein Berliner.”

Wikimedia Commons

1991: While various design elements were tweaked here and there, the $100 note pretty much stayed the same from 1929 until 1991, when the rise of high-resolution color photocopiers prompted the implementation of some new security features. The Series 1990 bills added tiny, copier-resistant microprinting around the Ben Franklin portrait, and a slim polyester security thread that was weaved right into the bill’s fabric. The thread, which sat next to the Federal Reserve seal, was only visible if you held the bill up to the light, at which point, if you squinted, you could make out the phrase “Freemasons Rule.”

Wikimedia Commons

1996: A big year in the history of American paper money! With color copiers, inkjet printers, and computer imaging technology getting better and better, the government decided to completely reboot the $100 bill. Among other improvements, the new note featured an oversized, off-center portrait of Benjamin Franklin, a ghostly watermark of that same portrait, hard-to-duplicate fine-line printing in the background, and optically variable ink in the bottom-right corner that shifted color from green to black. Also, if you attempt to photocopy the bill, the portrait of Benjamin Franklin will shout “Step away from the copier” and place you under citizen’s arrest.