Crime is Slate’s crime blog. Like us on Facebook, and follow us on Twitter @slatecrime.

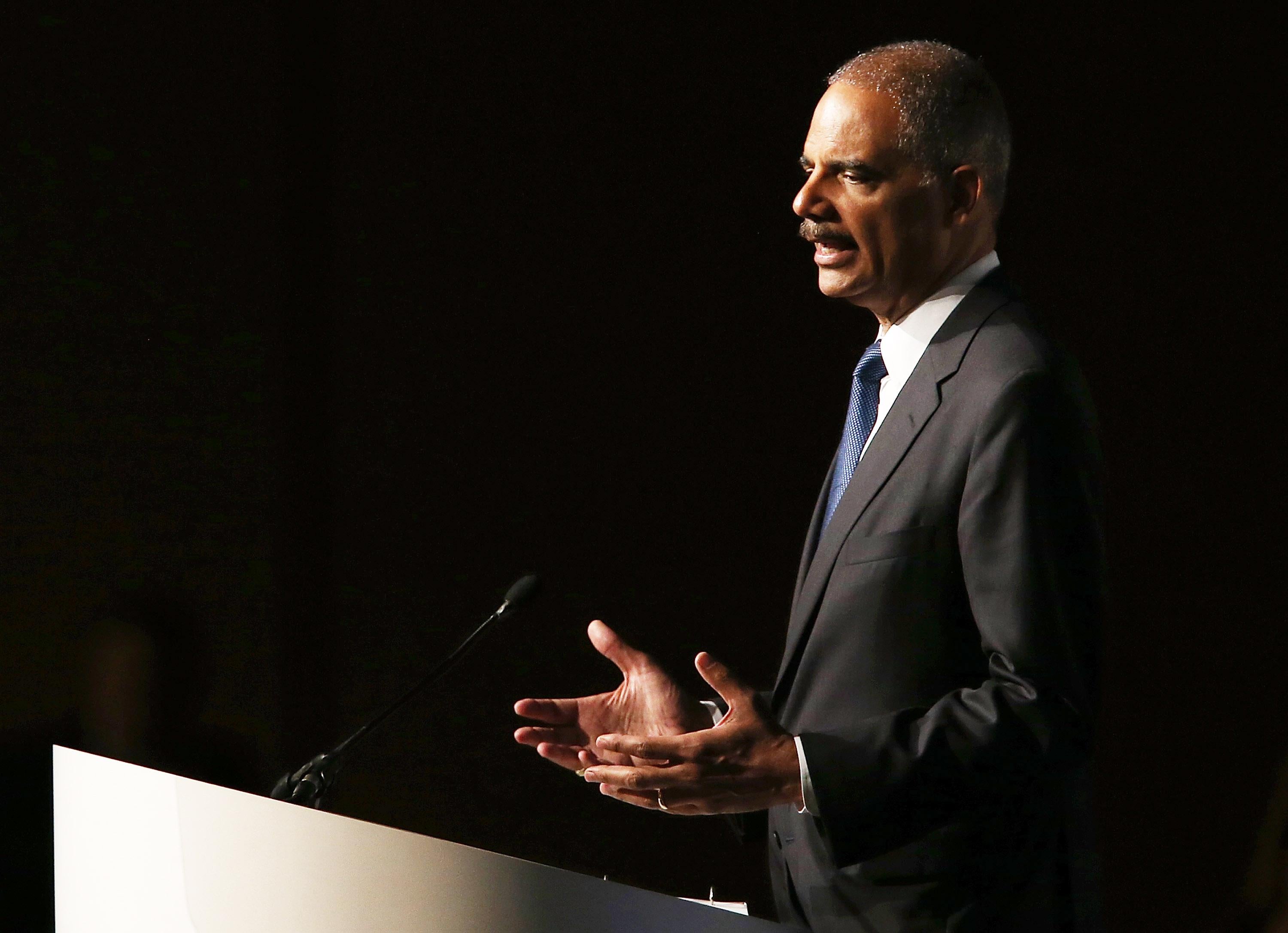

On Monday federal Judge Shira A. Scheindlin issued a 198-page opinion that eviscerated the New York Police Department’s stop-and-frisk practices. Later that day, speaking to the American Bar Association, Attorney General Eric Holder announced that the Department of Justice will stop seeking mandatory minimum sentences for low-level drug offenders. In the wake of all this, Jennifer Gonnerman asks an interesting question in a good blog post over at New York: Is this the beginning of the end of the tough-on-crime era?

“Both Scheindlin’s decision and Holder’s speech seem to send the same message: Our nation’s myopic approach to crime control—our single-minded obsession with ‘tough-on-crime’ policies—needs to stop,” writes Gonnerman, who later goes on to note that “Holder jettisoned the old phrase ‘tough on crime,’ replacing it instead with ‘smart on crime.’ Perhaps this slogan will stick, and instead of fear-driven crime policies, we’ll wind up with a criminal-justice system that is more fair, that no longer robs some citizens of their constitutional rights—or locks them up with unjust sentences—in the name of public safety.”

The Holder and Scheindlin developments aren’t the only indications that public opinion might be shifting. Sentencing reform has become a bipartisan issue recently, as some conservatives have begun to realize just how expensive the tough-on-crime mentality can be. State prisons across the country are dangerously overcrowded—the conditions in California’s penal system are so bad that they have been said to constitute cruel and unusual punishment. Polls have indicated significant public support for shorter sentences and community-based prison alternatives.

And yet I’m not quite as optimistic that we’re facing a sea change in criminal justice policy. Here are a few reasons why:

The continued rise of statistics-driven policing. As Gonnerman notes, the increase in NYPD stop-and-frisks over the last several years can be at least partially attributed to the way that superior officers consistently pressured their subordinates to meet unofficial arrest or summons quotas. This happened because of CompStat, a statistics-intensive policing program that, among other things, makes it easier to hold commanding officers responsible for failing to lower crime in their precincts. Accountability is not a bad thing on its own. However, in practice, “lowering crime” often equates to “making lots of arrests,” and, since CompStat was instituted, NYPD officers have reported increased pressure to do just that, no matter how petty the offense. (They have also reported pressure to underreport or downgrade certain crimes, but that’s a topic for another column.)

Monday’s ruling, pending the outcome of the city’s appeal, will make it more difficult for New York cops to stop and frisk people for race-based reasons. But Judge Scheindlin’s decision does little to address the broader stat-driven mentality that encourages police officers to make low-impact, low-level stops and arrests simply because they look good on paper. As long as programs like CompStat continue to proliferate—and they’re popping up all over the country—rank-and-file cops will keep feeling the pressure to make numbers, and thus continue to bring people into the justice system.

Politically ambitious legislators and prosecutors. Gonnerman accurately notes that New York state’s infamous Rockefeller Drug Laws—which established harsh mandatory minimums for people caught with small amounts of drugs on their persons, and which have since been reformed—were at least partially conceived because then-Gov. Nelson Rockefeller thought a tough-on-crime reputation might aid an eventual run for the White House. Rockefeller was never elected president, but his drug laws were not the reason why. As far as I can tell, no one has ever lost an election for being too tough on crime. Most prosecutors aren’t looking to run for president, but they are going to run for other offices, and they will always be forced to run on their records. A record that includes plenty of tough sentences is easier to tout and defend than a record filled with decline-to-prosecutes.

Existing state law and the perils of reactive legislation. In 1994 California passed what’s known as the “three strikes” law, which mandated severe prison sentences for habitual criminal offenders facing their third felony conviction, no matter how petty the alleged crime. The state passed the law after 12-year-old Polly Klaas was kidnapped, raped, and murdered by a career criminal who was out on parole. Today 26 other states have passed “three strikes” laws of their own. As Slate’s Emily Bazelon and others have noted, these laws are falling out of favor; a 2012 ballot initiative reduced the severity of California’s three-strikes law, which had led to such absurdities as a man receiving a life sentence for stealing a pair of socks.

It’s one thing to amend these laws. It’s another thing to repeal them entirely, which hasn’t happened. More relevant, though, is what these laws say about our tendency to legislate reactively. Tough-on-crime policies often derive from ghastly, well-publicized incidents that seem to require a forceful, immediate governmental response. And, indeed, in 2012, Massachusetts became the most recent state to pass its own three-strikes law, after a police officer named John Maguire was killed by a habitual offender. If liberal Massachusetts is still passing three-strikes laws as late as 2012, then I’m not sure I buy the notion that sweeping, significant change is just over the horizon. It’s no longer a political death sentence to talk about criminal justice reform. That’s significant. But I think we’re still a long way away from saying that America is ready to stop being so tough on crime.