Crime is Slate’s crime blog. Like us on Facebook, and follow us on Twitter @slatecrime.

There is much that is extraordinary about Judge Shira A. Scheindlin’s decision in Floyd, et al. v. City of New York, et al. The 198-page ruling, issued Monday morning, effectively dismantles the New York Police Department’s stop-and-frisk policy as it currently stands. Scheindlin rips apart the “NYPD’s practice of making stops that lack individualized reasonable suspicion,” appoints an independent monitor to help the department reform the policy and bring it in line with the law, and generally validates the notion that stop-and-frisk has been a colossal infringement on citizens’ civil rights. But even considering the sweeping language in her decision, the most extraordinary thing about Scheindlin’s ruling is the fact that it exists at all—that the NYPD didn’t see fit to reform itself in the face of such obvious abuses.

It has long been obvious that the NYPD has deliberately targeted young black and Hispanic men for stops and frisks, regardless of whether there was any reason to believe they were engaged in criminal behavior. Floyd v. City of New York, which was argued in a two-month trial this spring, did nothing to dispel that notion. In her ruling, Scheindlin finds that the department “has repeatedly turned a blind eye to clear evidence of unconstitutional stops and frisks,” and has let racial bias guide its actions. Given the amount of evidence in the case, it was the only possible conclusion.

But a long trial and a federal monitor certainly wasn’t the only possible resolution. As Scheindlin notes more than once in her ruling, the NYPD has had ample opportunity to change its ways over the past decade and a half. In 1999 a New York attorney general’s report “placed the City on notice that stops and frisks were being conducted in a racially skewed manner,” and recommended a “broad, public dialogue” about the policy. In 2003 the city settled the case of Daniels, et al. v. City of New York, which alleged that the NYPD was improperly stopping and frisking members of certain races; as part of the settlement, the department was charged with developing a written, binding anti-racial profiling policy, and with providing audit data about stops and frisks to the Center for Constitutional Rights. In 2010, after the Village Voice reported on secret audio tapes made by Officer Adrian Schoolcraft that showed commanding officers exhorting their subordinates to make quotas, the state passed a law prohibiting police departments from retaliating against officers who fail to meet those quotas. Throughout this time period, and especially over the past couple of years, the local and national media have increasingly criticized stop-and-frisk.

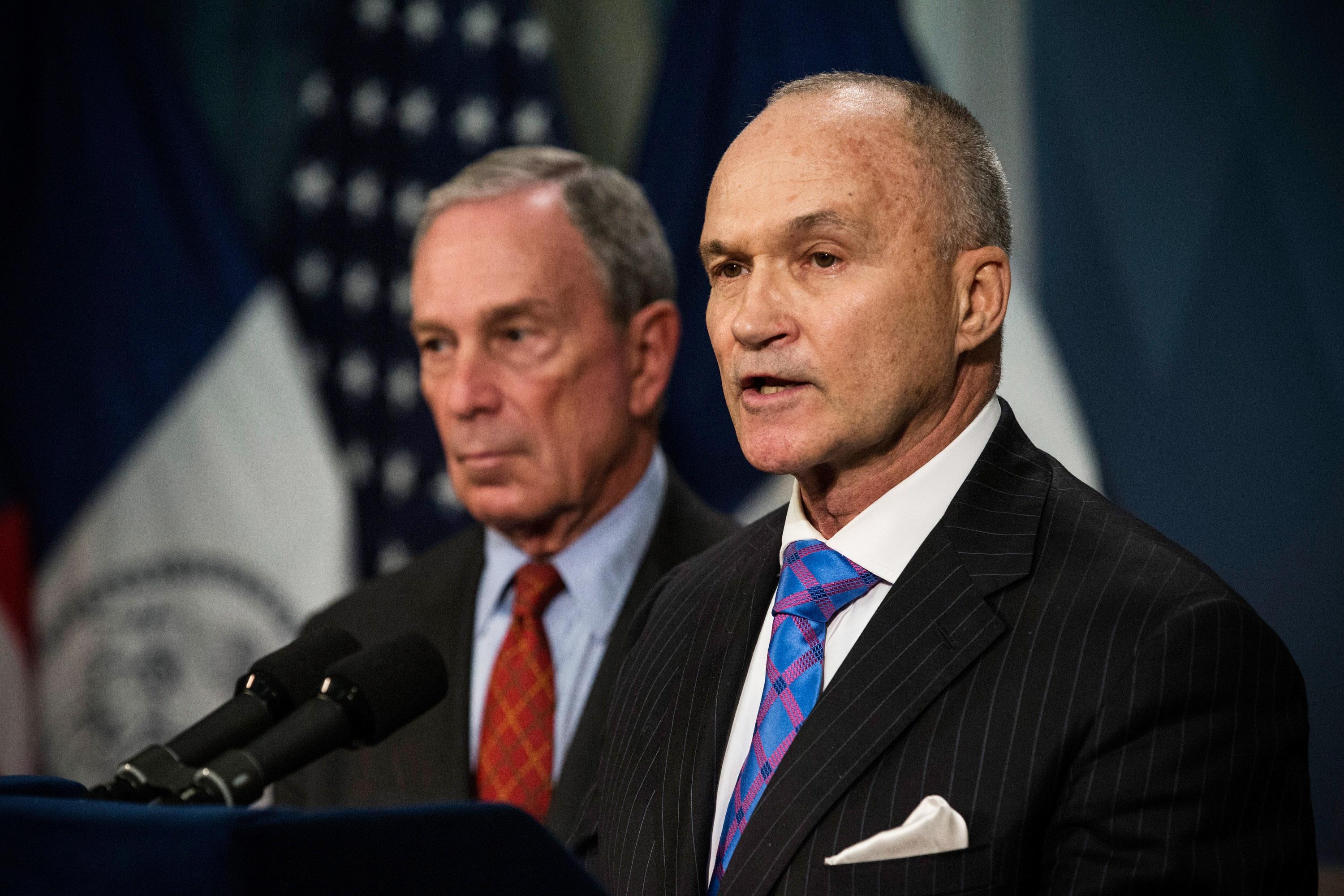

In every instance, the NYPD’s response has been to ignore the criticisms and resist all attempts at reform. The 1999 AG report was roundly ignored. The Daniels settlement was met with “significant non-compliance” and an increase in stop-and-frisks, according to the Center for Constitutional Rights. The 2010 Quota Law was sidestepped; instead of specific numerical quotas, the department started encouraging non-numerical “performance goals.” Journalists’ criticisms have been brushed off, most vocally by stop-and-frisk fanboy Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who has asserted that the disproportionate stopping and frisking of young blacks and Hispanics is justified because, after all, they are the ones committing crimes. (Scheindlin forcefully rebuts this line of thought, noting that “there is no basis for assuming that an innocent population shares the same characteristics as the criminal suspect population in the same area.”)

Indeed, the zeal with which both Mayor Bloomberg and Police Commissioner Ray Kelly have defended and encouraged the use of the ineffective, racist stop-and-frisk policy has been startling. “NYPD personnel experienced or were aware of pressure to increase the number of stops after the introduction of Compstat, and especially after the arrival of Mayor Bloomberg and Commissioner Kelly,” Scheindlin writes. Enthusiasm runs downhill, and, to an extent, the department has been merely following its leaders’ examples.

But the story of stop-and-frisk is also a story of the NYPD’s antagonistic relationship with many of the communities it serves, and the contempt it feels for citizens who would presume to tell the police how to do their jobs. “We own the block. They don’t own the block, all right? They might live there but we own the block. All right? We own the streets here. You tell them what to do,” one lieutenant says in the Schoolcraft tapes, exhorting his officers to enforce their will on the streets of Bedford-Stuyvesant. Stop-and-frisk has survived for as long as it has because the disenfranchised residents that fall victim to the policy generally have no recourse against inappropriate police behavior. They know it and the cops know it. Citizens can bring their complaints to the Civilian Complaint Review Board, sure—but the CCRB’s job ends when it reports a substantiated complaint to the Department Advocate’s Office, or DAO, which handles things from there. Yet Scheindlin found that “if the CCRB bases its findings on a credibility determination in favor of a witness and against a police officer, the DAO will as a rule reject the CCRB’s findings.” Stop-and-frisk has persisted because the average person believes she can’t do anything to stop it, and the average person has been exactly right.

Scheindlin did not find that stop-and-frisk itself was unconstitutional, only that it was unconstitutionally applied. The independent monitor, a former federal prosecutor named Peter L. Zimroth, will work with the NYPD to reform its internal policies and institutional culture, and bring stop-and-frisk in line with the law. And these reforms will have to start at the top. In a 2010 meeting with New York state Sen. Eric Adams, who is a former NYPD officer, Commissioner Kelly allegedly admitted that “he focused on young blacks and Hispanics ‘because he wanted to instill fear in them, every time they leave their home, they could be stopped by the police.’ ” That’s a horrible thing to want, both as a human being and as a police officer. As Scheindlin notes:

No one should live in fear of being stopped whenever he leaves his home to go about the activities of daily life. Those who are routinely subjected to stops are overwhelmingly people of color, and they are justifiably troubled to be singled out when many of them have done nothing to attract the unwanted attention. Some plaintiffs testified that stops make them feel unwelcome in some parts of the City, and distrustful of the police. This alienation cannot be good for the police, the community, or its leaders. Fostering trust and confidence between the police and the community would be an improvement for everyone.

Of course, a federal judge cannot mandate trust between a police department and the community it serves. She can, however, take steps to ensure that the police respect the rule of law—a necessary condition if trust is to eventually develop. Scheindlin’s landmark decision today is one major step in that direction. Now it’s time for the NYPD to take a few big steps of its own.