Crime is Slate’s crime blog. Like us on Facebook, and follow us on Twitter @slatecrime.

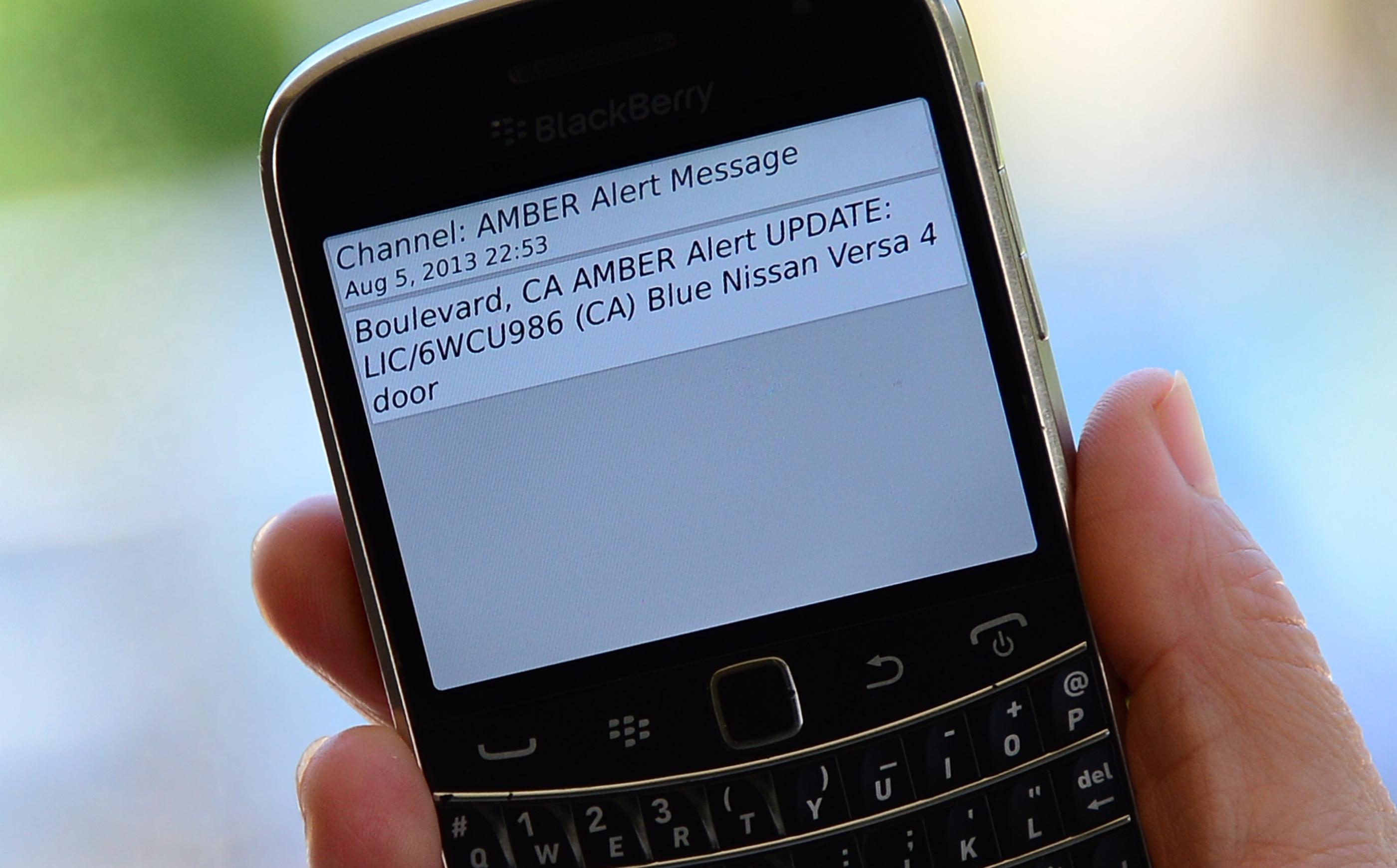

On Monday night, many Californians awoke to the sound of an unexpected message on their mobile phones. The message—which, according to the Los Angeles Times, was accompanied by “a 10-second spurt of high-pitched noise and buzzing”—read “Boulevard, CA AMBER Alert. UPDATE: LIC/6WCU986 (CA) Blue Nissan Versa 4 door.” That was it—there was no other context to explain why this data was important.

The message was an AMBER Alert sent automatically to California cell phones by the Wireless Emergency Alert system; two San Diego-area children had been kidnapped, and the alert was intended to encourage community members to keep their eyes open and help find them. (As of this writing, the children are still missing.) Instead, many of them were upset and confused that they’d been bothered by some jarring, vague message that they hadn’t signed up to receive. (The Wireless Emergency Alert is an opt-out system.) “New irrational fear: the sound the iPhone makes during an Amber Alert. #nosleep,” wrote Twitter user @MegTurney, summarizing the feelings of many. Marc Klaas, whose daughter, Polly, was kidnapped and murdered in 1993, complained to the Los Angeles Times about the alert’s “incredibly harsh sound” that “provides you with almost no information.” Klaas went on to that say that “the intention is good, but the application itself is pretty awful.” But I’ll go him one better: The AMBER Alert system doesn’t work.

The “AMBER” in AMBER Alert stands for “America’s Missing: Broadcast Emergency Response.” But it also refers to Amber Hagerman, a 9-year-old girl who was kidnapped and murdered in 1996. Back then, some argued that Hagerman’s death could have been prevented if there had been some way for police to inform the public about the sort of car the abductor was thought to be driving. Hence the creation of the AMBER Alert: “a voluntary partnership between law-enforcement agencies, broadcasters, transportation agencies, and the wireless industry, to activate an urgent bulletin in the most serious child-abduction cases.”

The idea was this: When a child was kidnapped, the system would disseminate relevant data—the child’s name, the make and model of the abductor’s car—via signs, radio bulletins, and other methods, in hopes that alert community members might help the police locate the missing child before it was too late. It’s a great concept that has led to some high-profile successes—like the case of Tamara Brooks and Jacqueline Marris, two Los Angeles teenagers who were adbucted in 2002, only to be safely recovered hours later thanks to tips that came in after an AMBER Alert was issued.

But the system rarely works as well as that. In a 2008 article in Criminal Justice Review titled “Child Abduction, AMBER Alert, and Crime Control Theater,” Timothy Griffin and Monica K. Miller argued that “AMBER Alert has not achieved and probably cannot achieve the ambitious goals that inspired its creation.” Griffin and Miller examined data from hundreds of AMBER Alerts issued between 2003 and 2006, and dubbed the AMBER Alert system a “theatrical policy” that was largely ineffective in helping save kidnapped children. “In most cases where they were issued, Griffin found, Amber Alerts played no role in the eventual return of abducted children,” the Boston Globe wrote in 2008. “Their successes were generally in child custody fights that didn’t pose a risk to the child. And in those rare instances where kidnappers did intend to rape or kill the child, Amber Alerts usually failed to save lives.”

Why have AMBER Alerts been ineffective? As a 2007 Pacific Standard article notes, most kidnapped children who eventually end up murdered are killed within three hours of their abduction. Yet AMBER Alerts are rarely issued within that critical window. It takes time for the authorities to get their act together, and by the time the alert goes out, it is often too late to make any difference.

In any event, those sorts of kidnappings are very rare. The vast majority of child abductions in this country are committed by relatives or acquaintances—estranged parents and such who usually mean the children no harm. Even though AMBER Alerts are only supposed to be issued in “the most serious child-abduction cases,” they are nevertheless used in domestic cases like these—cases where, Griffin argues, AMBER Alerts might actually serve to escalate an otherwise manageable situation. “We looked at a parental abduction where the dad was located thanks to a citizen tip prompted by an AMBER Alert,” Griffin told Pacific Standard. “Law enforcement swooped in there. There was a big standoff, and the guy ultimately killed himself. We coded that case as ‘AMBER Alert saved a kid from a dangerous situation.’ But for all we know, the AMBER Alert made it a dangerous situation.”

So should we dispense with AMBER Alerts entirely? The alerts are often issued too late to make a difference; the information contained is often vague and poorly targeted. The California alert I mentioned above reportedly went out to people across the entire state, not just in the areas where the kidnapper was likely to be. If you’re regularly bombarded with text messages about a kidnapping that happened hundreds of miles away, you’re eventually going to start disregarding all of the alerts you receive. That’s not an effective way to raise public awareness.

The AMBER Alert system has had its successes. That needs to be said. And its defenders say that the system is better than nothing; that it’s inexpensive to run; that even if it’s not always effective, the chance that it might eventually save one kidnapped child’s life makes its continued existence worthwhile. I disagree. The continued existence of a dysfunctional program can stop people from trying to come up with a better solution, one that might save two children’s lives, or 10, or 100. And it’s clear that, when it comes to stopping child abductions, we need a better community alert system than the one we’ve got.