Crime is Slate’s crime blog. Like us on Facebook, and follow us on Twitter @slatecrime.

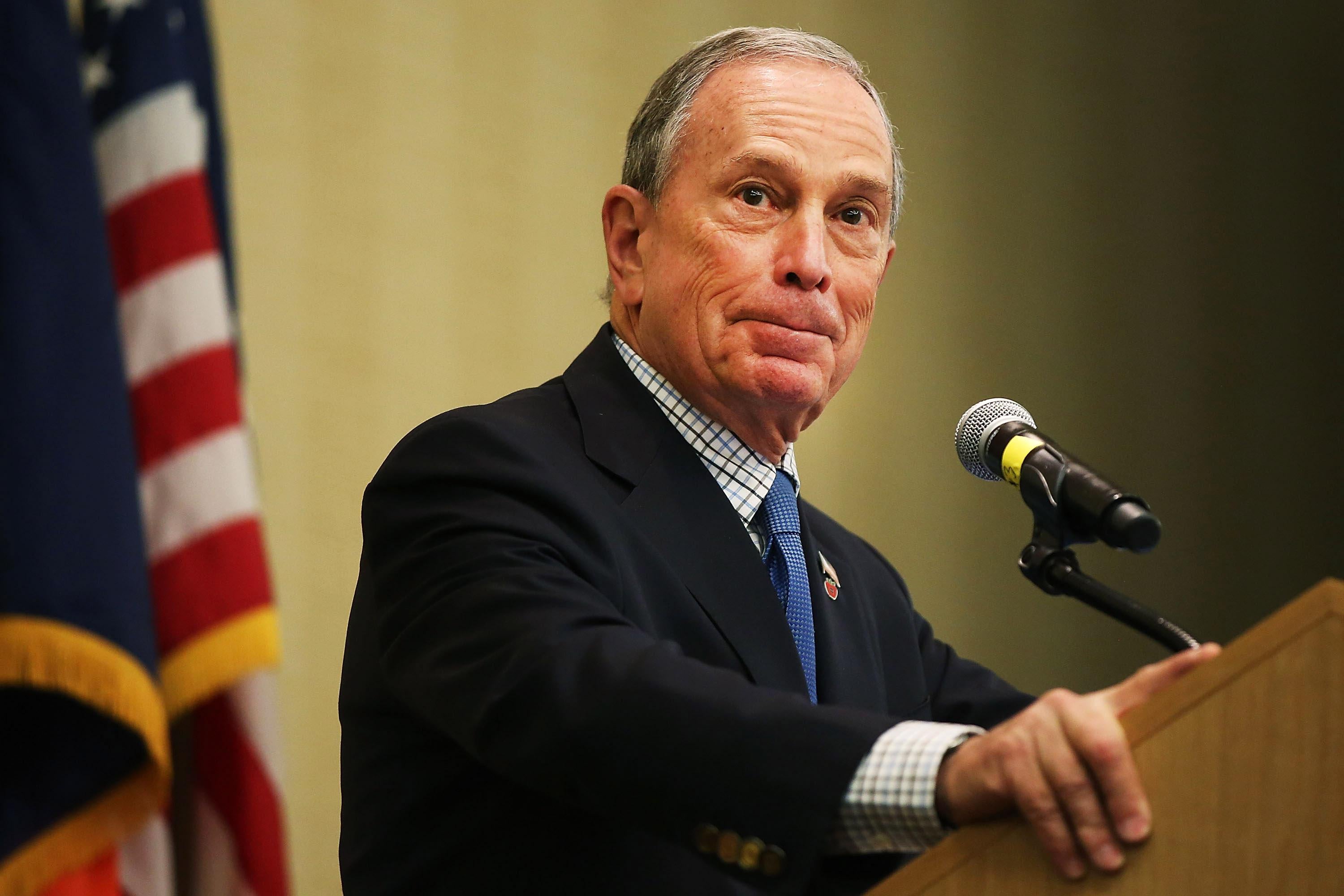

In the waning days of his administration, New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg—long known as the “education mayor”—seems determined to cultivate a reputation as the “police harassment mayor.” More than once over the past few months, Bloomberg has vigorously defended the New York Police Department’s controversial stop-and-frisk program, even as the policy is being challenged in court and in the New York City Council, where two recently passed bills would appoint an inspector general to monitor the NYPD and make it easier for New Yorkers to sue the department if they felt they had been unfairly stopped.

Although both bills were passed with veto-proof majorities, Bloomberg has promised to veto them all the same. A mayoral veto would seemingly just delay the inevitable—the council would just override it and the bills would become law. Even so, Bloomberg is actively working to convince council members and the general public that the bills are worthless. On Friday, Bloomberg ripped the legislation during a radio show appearance. “These are bad bills,” Bloomberg said. “The racial profiling bill is just so unworkable. Nobody racially profiles.”

“Nobody racially profiles” is a curious statement. Every year since 2003, blacks and Latinos have consistently accounted for around 85 percent of stop-and-frisk selectees; according to 2010 census data, blacks and Latinos make up 52.6 percent of New York City’s total population. “Even in neighborhoods that are predominantly white, black, and Latino New Yorkers face the disproportionate brunt,” reports the New York Civil Liberties Union. “For example, in 2011, Black and Latino New Yorkers made up 24 percent of the population in Park Slope, but 79 percent of stops.”

It is hard to see how any reasonable person could look at that data and say that “nobody racially profiles,” but let’s give Bloomberg a fair hearing. Perhaps he meant to argue that the NYPD does not choose its stop-and-frisk candidates solely on the basis of race. And, indeed, Bloomberg essentially went on to say that the only reason blacks and Latinos are stopped so often is that stop-and-frisk demographics correspond to the demographics of criminal suspects:

“There is this business, there’s one newspaper and one news service, they just keep saying, ‘Oh it’s a disproportionate percentage of a particular ethnic group,’ ” he went on. “That may be, but it’s not a disproportionate percentage of those who witnesses and victims describe as committing the murder. In that case, incidentally, I think we disproportionately stop whites too much and minorities too little.”

But most stop-and-frisks have nothing to do with solving “the murder,” or other specific crimes. As the NYCLU found, “Only 11 percent of stops in 2011 were based on a description of a violent crime suspect.” The rest of them were just random stops, and most of the people who are stopped turn out to be clean. Since 2003, between 87 and 90 percent of the hundreds of thousands of people stopped each year have turned out to be completely innocent of any wrongdoing.

The NYPD requires its officers to fill out paperwork justifying every single stop-and-frisk. The justifications can be maddeningly vague; people are regularly stopped, for example, because they are “carrying [a] suspicious object,” or “wearing clothes commonly used in a crime,” or because of “furtive movements” or a “suspicious bulge.” A stop can be elevated to a frisk for similarly vague reasons: “furtive movements,” “verbal threats by suspect,” if suspects are wearing “inappropriate attire for season,” if they “refuse to comply with officer’s directions.”

It does not take much of an imagination to see how these justifications give NYPD officers latitude to stop anyone, at any time, for any reason. How do you define “suspicious object”? What about “furtive movements”? I am an absent-minded person, and often will go outside without any sense of where I’m going or how to get there; thus, while walking, I will sometimes abruptly change direction, or suddenly pause and try to remember why I left my apartment in the first place. I am sure that these movements could be described as “furtive.” And yet I’ve never once been stopped by the police—even during the years when I lived in a neighborhood where gunshots and drug deals were common.

But, then, I’m a tall white dude. In that sense, I was born lucky. The same can’t be said for men like medical student David Floyd, who was stopped and frisked while walking home from the subway by police officers who refused to give a reason for the stop; or Lalit Clarkson, an assistant teacher who was stopped after buying chips at a bodega by police who claimed he was seen “coming from the vicinity of a known drug haven”; or David Ourlicht, a St. John’s University student stopped three times in six months back in 2008. All three men are black. All three men had done nothing wrong.

All three men are also plaintiffs in Floyd v. New York, a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk program. The case was heard by U.S. District Court Judge Shira Scheindlin this spring; she is expected to issue her ruling later this year. It is very possible that Scheindlin will find stop-and-frisk unconstitutional, thus ending the policy as we know it today. This would be a good thing. The NYPD’s stop-and-frisk program is totally, unquestionably racist. But that’s only half the story. Stop-and-frisk is also totally, unquestionably ineffective.

So why, at this late moment in his mayorality, is Michael Bloomberg so invested in defending the program? As Azi Paybarah wrote today at Capital New York, “with the final city budget passed, Bloomberg seems to be acting out an adult form of senioritis, no longer calibrating his actions, or showing much interest in the patient work of giving cover to potential allies or finding pet causes with which to entice lawmakers to his side.” Bloomberg may well find it liberating to just go out and say what he thinks. But frankness can have unforeseen consequences. This Sunday, on Face the Nation, NAACP President Benjamin Jealous said—somewhat hyperbolically—that Bloomberg is “really trying hard to make himself the Bull Connor of the 21st century.” That’s not the sort of legacy Bloomberg, or any other mayor, would want to leave behind.

More coverage of stop-and-frisk: The Heroic New York City Cop Who’s Trying to Stop Stop-and-Frisk; Mayor Bloomberg: If You Dare Criticize the NYPD, the Terrorists Win; A Ringing Defeat for Stop-and-Frisk and a Huge Win for Civil Liberties; How About a Friendly Frisking?: The Myth of the “Consensual” Police Encounter.