Crime is Slate’s crime blog. Like us on Facebook, and follow us on Twitter @slatecrime.

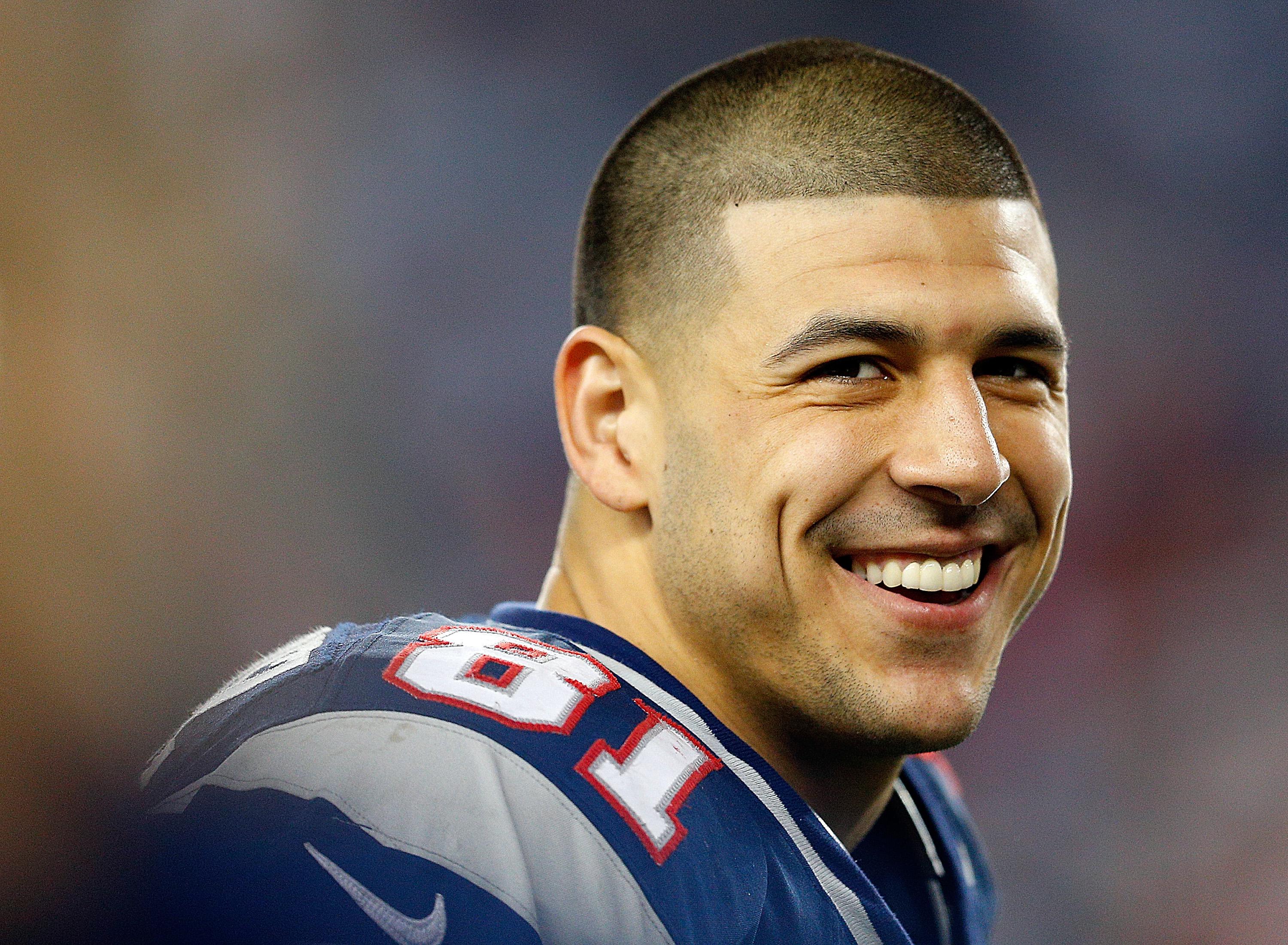

It was a bad morning for Aaron Hernandez. First, he was arrested, capping off a week’s worth of will-they-or-won’t-they speculation from football fans and the media. Soon thereafter, Hernandez was released by the New England Patriots, the team for which he had scored 18 touchdowns over the past three years. And finally, he was arraigned at Attleboro District Court, where he was charged with murder as well as five gun-related counts. Hernandez has pleaded not guilty.

The order of operations here was a bit unusual, with the Patriots acting before Hernandez had officially been charged. In a statement, the team announced that “We realize that law enforcement investigations into this matter are ongoing. We support their efforts and respect the process. At this time, we believe this transaction is simply the right thing to do.”

It sounds so simple—if a professional athlete is charged with or implicated in a crime, release him. The Patriots were well within their rights to rid themselves of Hernandez, and there’s a lot of precedent for NFL teams doing the same—if not releasing a player before he’s even been charged with a crime. (You’d have to guess that the Patriots knew what was coming.)

Most NFL teams have shown a willingness to get rid of troubled players who are only marginal contributors on the field. On Tuesday, for instance, Cleveland Browns rookie linebacker Ausar Walcott was arrested and charged with attempted murder after he allegedly punched a man in the head at a nightclub. On Wednesday the Browns released Walcott, an undrafted free agent who wasn’t likely to help the team all that much anyway. In January, Steelers running back and kick returner Chris Rainey was arrested after allegedly hitting his girlfriend in the face. Kick returners are a cheap commodity; the Steelers released Rainey within hours of his arrest. In December 2011, Chicago Bears wide receiver Sam Hurd was arrested and charged with attempting to buy and distribute large quantities of marijuana and cocaine. Hurd, who mostly played on special teams, was waived by the Bears days after his arrest.

The decision to cut ties usually isn’t made so quickly when the player is a star. In 2007, Atlanta Falcons quarterback Michael Vick was indicted on dogfighting charges. This prompted an “incredibly difficult decision” for the Falcons, because, as a USA Today article put it at the time, “Vick sells merchandise. Vick sells tickets.” Even though Vick was sentenced to prison that same year, the Falcons didn’t release him until June 2009—one month after he got out of prison. In November 2008, star New York Giants wide receiver Plaxico Burress accidentally shot himself in the thigh with his own pistol at a nightclub in New York City. Burress, who didn’t have a valid pistol permit, was suspended by the Giants—but he wasn’t released until April 2009, when it was becoming clear that he would probably spend time in prison.

Dogfighting and self-wounding aren’t murder, you say? Well, let’s look at a murder case. In 2000, Baltimore Ravens linebacker Ray Lewis was charged with two counts of murder for his alleged role in the stabbing deaths of two people during a post-Super Bowl scrum. In the immediate aftermath of the charges, as happened with Aaron Hernandez, the media started scrutinizing Lewis’ past. “Ray hangs with a tough crowd,” one person told a Baltimore Sun reporter in a February 2000 article that also noted Lewis’ troubled childhood and some battery allegations he had faced in college. And yet the Ravens stood by Lewis, telling the media they would let the case run its course before deciding whether to release him. Eventually, the murder charges were dropped, and Lewis pleaded guilty to obstruction of justice. He played 12 more seasons with the Ravens, and retired this year as the most decorated and beloved player in franchise history.

There are a lot of similarities between Lewis’ case and Hernandez’s current legal troubles. But Hernandez, though he’s a very good player, is not a superstar—nobody’s coming to Foxborough to see him catch a few passes per game. The Patriots can survive without him—“very good” isn’t enough to excuse Hernandez for violating “The Patriot Way.” I’m not actually sure what “The Patriot Way” means, but I suspect it’s something like, “Unless you’re Tom Brady, don’t get yourself caught up in a sordid murder investigation, because we will release you and probably sue to recover your signing bonus.” After all, it’s the right thing to do.