Six months ago today, an odd, angry kid named Adam Lanza woke up, grabbed a couple of guns, and went looking for easy targets. He started with his mother, who had taught him to shoot, and who was probably still asleep when Lanza entered her bedroom and put those lessons to use, shooting her four times in the head. Next, he moved on to children, 20 of them, huddled in the first-grade classrooms at Sandy Hook Elementary School. Lanza shot and killed them and six adults with 154 rounds from an AR-15-style semi-automatic rifle. His final target was himself: with police approaching, Lanza traded his rifle for a Glock 10mm handgun, chambered a round, and shot himself once in the head.

Two days later, in a speech in Newtown, President Obama took aim at what, at the time, seemed like another easy target. “We can’t accept events like this as routine,” he said, promising to use all the powers of his office to make gun control legislation a renewed priority in Washington. “Are we really prepared to say that we’re powerless in the face of such carnage? That the politics are too hard? Are we prepared to say that such violence visited on our children year after year after year is somehow the price of our freedom?” It was a speech the country needed to hear. It was a speech that meant nothing.

Over the past six months, every major federal gun control initiative has either stalled or failed. Talk of a new federal assault weapons ban went nowhere. A bill to expand background checks failed in the Senate. More has happened on the state level, but not much more. In a Los Angeles Times column today, two executives from the Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence noted that, since Sandy Hook, “six states have strengthened firearms laws.” But as time has passed, enthusiasms have waned. Although New York passed a stringent gun control bill one month after the Sandy Hook shootings, it has since been challenged in court, and there is talk of its repeal. This Thursday, the governor of Nevada vetoed a gun control bill that would have banned private weapons transfers. Last month, the Illinois state legislature passed a bill legalizing concealed weapons.

It’s no big surprise that the Sandy Hook massacre failed to immediately galvanize changes in the nation’s gun laws. Grief and rhetoric are easy to get right; legislation is harder. But I am surprised that the debate has become so bloodless. In an absolutely wrenching piece for the Washington Post, Eli Saslow wrote about Mark and Jackie Barden, whose son, Daniel, was shot and killed at Sandy Hook. Since then, the Bardens, emotionally broken, have traveled the country lobbying for stronger gun laws. They have been taught to mute their anguish and speak in polished, sensible talking points:

But the past five months had taught Mark and Jackie that simplicity and innocence didn’t work in politics. Neither did rage or brokenness. Their grief was only effective if it was resolute, polite, purposeful and factual. The uncertain path between a raw, four-minute massacre and U.S. policy was a months-long grind that consisted of marketing campaigns, fundraisers and public relations consultants. In the parents’ briefing book for the Delaware trip, a press aide had provided a list of possible talking points, the same suggestions parents had been given in Illinois, New York, New Jersey and Connecticut.

“We are not anti-gun. We are not for gun control. We are for gun responsibility and for gun safety laws,” one suggestion read.

Though the Bardens have been taught to temper their emotions, gun control opponents are under no such restrictions. For firearms fanatics, inarticulate anger has always been a powerful political weapon. The Senate background checks bill failed in part because many gun owners were convinced—urged on by the gun lobby—that it would mandate “universal registration of all firearms and their owners,” even though the bill contained no such provision. Grief is unwelcome in the halls of Congress. Rage is how business gets done.

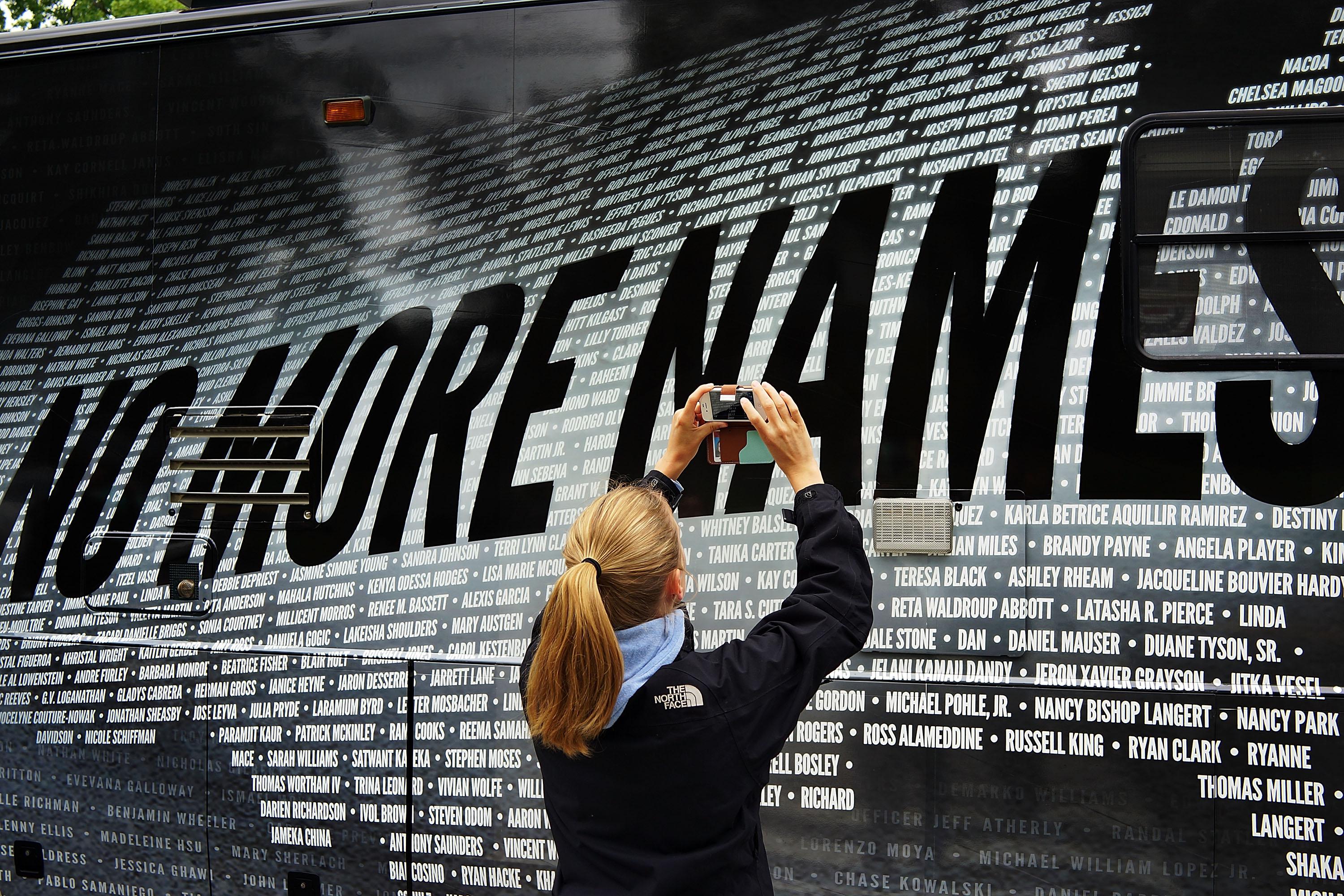

When you remove honest grief from the gun control debate, you also remove much of the urgency. That’s not to say that we should legislate reactively. Laws passed in haste are often bad ones. But gun control advocates will never be effective if they relent to the pressure to turn gun violence into an abstraction, deemphasizing personal stories in favor of neutered phrases, facts, and figures. In the six months since Sandy Hook, the gun control debate has been generalized; as the grief gardens dismantle and the faces of the victims fade, it will become harder to remember why gun control once seemed so urgent.

For those of us who were there, it is impossible to forget. I attended Daniel Barden’s memorial service last December. I stood outside for an hour, in the cold and the rain, in a line that reached all the way across the parking lot of St. Rose of Lima Catholic Church. When I finally made it inside, the church was choked with mourners, in a scene that had been playing out all week across Newtown: 20 funerals, 20 miniature coffins, thousands of flowers, millions of tears.

“The Sandy Hook shooting is the sort of inflection point that, throughout our history, has led us to choose what sort of country we are, want to be, and will become,” I wrote at the time.

That night, that week, the choice did seem easy. Twenty children were killed in a school, less than two weeks before Christmas. These children had names and faces, likes and dislikes, vague and fanciful notions of the things they might do and the people they might become. They were killed in the morning, in less than five minutes, by 154 rounds fired from a semi-automatic rifle by a mentally disturbed man who should not have had access to a gun. They didn’t have to die. Either you choose to acknowledge those facts, or you choose to run from them.

In the week following the Sandy Hook shooting, the people of Newtown and the wider world chose to face down the horror. Gun control legislation has failed because, since then, we have chosen to turn away.