Crime is Slate’s crime blog. Like us on Facebook, and follow us on Twitter @slatecrime.

Alan Prendergast at Westword has a sad and telling item about problems at a Colorado toxicology lab that conducts blood and drug tests for police departments statewide. As Prendergast writes, hundreds of DUI convictions are being thrown into doubt after a Colorado attorney general report detailed myriad concerns about the lab’s procedures: refrigerators containing blood and urine samples being left unlocked and unsecured; technicians being put to work with inadequate training; lax supervision of testing procedures. The story also mentions the alleged “pro-prosecution bias” of one of the lab’s supervisors.

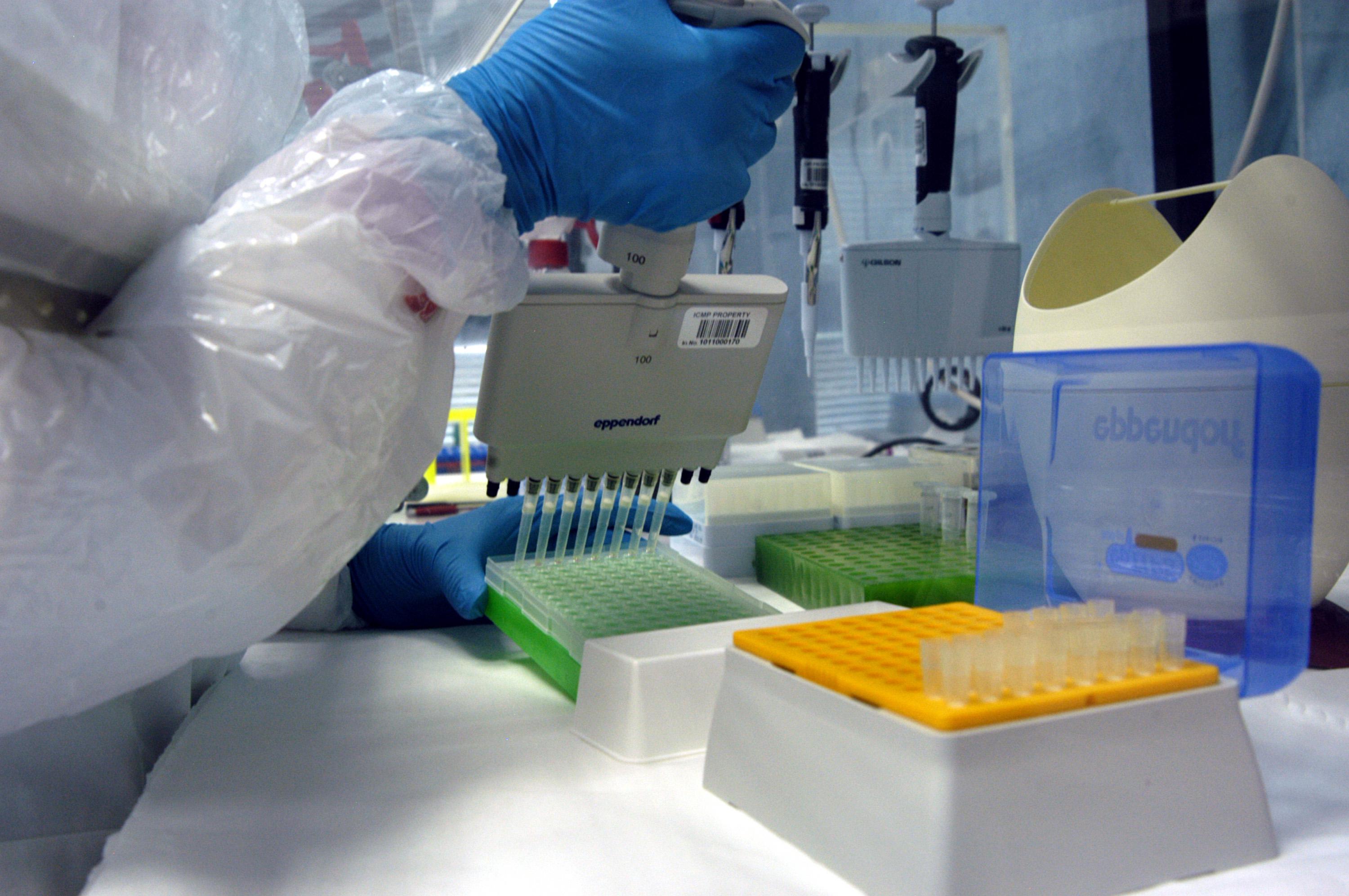

This isn’t the first time I’ve written about dysfunctional crime labs, and it probably won’t be the last. Suffice to say that the crime labs depicted on television programs like CSI are better-equipped and more functional than the vast majority of their real-world equivalents. Many actual crime labs are systemically error-prone, staffed with technicians who are often overworked and undertrained, supervised by officials who consider it their jobs to send bad guys to jail rather than ascertain the facts by rigorously analyzing physical evidence. Take Annie Dookhan, the Boston-area chemist for a state drug lab who stands accused of consistently mishandling evidence samples in drug cases over several years; Dookhan’s mistakes have led to thousands of convictions being thrown out or reviewed. Or Serrita Mitchell, the New York City technician accused of mishandling DNA samples in at least 26 rape cases.

Maybe Dookhan and Mitchell are outliers. The problem, though, is that crime labs are not operationally transparent, and issues like these generally only come to light after evidence is leaked or its release is compelled via lawsuits. Governments tend to release this information grudgingly. As Prendergast writes in Westword, the Colorado attorney general had been sitting on the report for three months, meaning that, in that period, DUI cases were allowed to come to trial even though the state knew that the lab processing evidence in those cases had credibility issues.

This problem seems a bit more urgent now that the Supreme Court has ruled that police departments can collect DNA samples from people who have merely been arrested, not convicted. This means that more DNA will now be collected than ever before. How will these samples be transported and stored? Who will be doing the analysis? What safeguards are in place to insure the professionalism, neutrality, and competence of the analysts? These questions need to be publicly asked and definitively answered before more mistakes like these have a chance to happen.