Crime is Slate’s crime blog. Like us on Facebook, and follow us on Twitter @slatecrime.

On Tuesday, the National Transportation Safety Board issued a report offering several recommendations on how to reduce drunk driving in the United States. The most newsworthy idea: States should lower their blood-alcohol-content thresholds from the current 0.08 to 0.05. Back during the Clinton presidency, the federal government prevailed on all 50 states to lower the BAC threshold from 0.10 to 0.08. It took a lot of work to implement that last drop-off, however, and as my colleague Josh Voorhees explained yesterday, this new proposal won’t likely go anywhere given the do-nothingness of the current Congress.

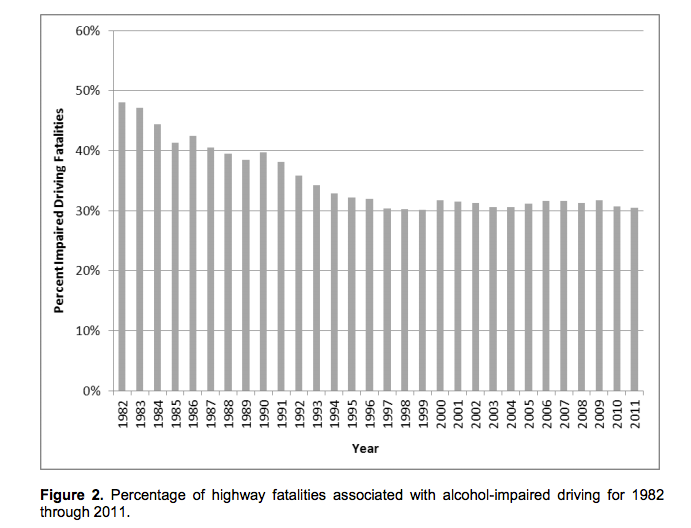

That might not be the worst outcome. If we’re going to have drunk-driving laws, then, yes, at some point there needs to be a cutoff at which society says, “hand over the keys, you’re drunk.” But it’s not clear that 0.05—the equivalent of three beers in 90 minutes for a 180-pound man, according to the New York Times—is that level. The NTSB report admits that “the majority of alcohol-impaired drivers in fatal crashes have BAC levels well over 0.08.” According to the NTSB’s own report, the yearly rate of alcohol-impaired driving fatalities has remained relatively stable since 1995, despite the big federal push to move from 0.10 to 0.08. As the NTSB chart below shows, the “proportion of [highway] fatalities associated with alcohol-impaired drivers has remained between 30 and 32 percent” in every calendar year since 1995.

National Transportation Safety Board

Should we expect that dropping the limit to 0.05 will make any difference?

The NTSB says it will. It argues that decreasing the BAC limit affects the “behavior of drivers at all BAC levels.” As a result, such a move “could reasonably be expected to have a broad deterrent effect, thereby reducing the risk of injuries and fatalities from crashes associated with impaired driving.” Though the NTSB doesn’t explain why moving from 0.08 to 0.05 will mean fewer fatalities when going from 0.10 to 0.08 had little effect, this does at least spell out the theory. The point of decreasing the BAC limit isn’t to target people who drink a little. It’s to target people who drink a lot, and hopefully get them to moderate their behavior.

The tradeoff, then, would be that people who likely aren’t a danger on the roads will be snared in a net designed to catch bigger, drunker fish. That might make sense as public policy—it’s perhaps better to arrest a few non-dangerous people if it’s going to save lives. But if we’re going to make it easier to penalize people for drinking and driving, we should also think about ways to incentivize people to follow the law. That means offering active incentives for people not to drive home.

As NYU public health professor Barron Lerner has written, a “multifaceted public health approach” to reducing drunk driving fatalities might be more effective than strictly punitive methods. This public health approach might include increased use of ignition interlocks and higher-visibility DUI enforcement, both of which the NTSB also recommended in its report. It also might help to reduce the barriers to calling a taxi.

I’d wager that, after a night out at the bars, most people decide to drive home for simple reasons. Sure, they probably often misjudge just how drunk they are. But, also, taxis can be expensive. Leaving your car on the street also leaves you open to a parking ticket. It’s also a pain to go back and pick up the car the next morning.

There are ways for the government or other agencies to help reduce those barriers. In the Washington, D.C. area, for example, a group called the Washington Regional Alcohol Program sponsors a holiday program called SoberRide, which offers free cab rides home (up to a $30 value) for people who’ve had too much to drink. Since its inception in 1993, the program has given out more than 55,000 free cab rides. (I can’t say for sure that there’s any causation here, but in 2011, D.C.’s rate of drunk driving fatalities per 100,000 residents was the lowest in the country.)

Similarly, it wouldn’t take much to convince towns and cities to excuse parking tickets for drunk people who take cabs home. And in certain states, the AAA Motor Club and Budweiser have sponsored a holiday program called “Tow to Go,” in which a AAA tow truck will tow your car home, free of charge, while you ride in the truck with the driver.

While the debate over the BAC limit will get more attention, policymakers should focus on testing these sorts of pilot programs in areas with extremely high DUI rates. It wouldn’t cost much—you could get the big liquor and beer companies to help fund it, as they do in D.C.—and it would help us learn whether the carrot works as well as the stick when it comes to reducing drunk driving fatalities.