Crime is Slate’s crime blog. Like us on Facebook, and follow us on Twitter @slatecrime.

My recent post on cooking-oil theft in the United Kingdom got me thinking about other contraband oils, and the days when margarine was bootlegged like moonshine. Yes, I said margarine. Though you know and tolerate it today as a vaguely palatable substitute for delicious creamery butter, margarine used to be heavily regulated in the United States—in some states, it was even banned—and bootleggers actually went to jail for selling the stuff. As a 1925 paper from the Institute of Margarine Manufacturers put it, margarine “has been unjustly discriminated against by many legislative bodies. And it has been misrepresented by many selfish as well as by many misinformed persons.”

Margarine was invented in 1869 by a chemist named Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès, after the French government sponsored a contest to come up with an inexpensive butter substitute. The idea, according to a 1925 paper in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, was to “furnish sailors and people of limited means with a cheap, wholesome fat of high dietetic value.” Though debatably wholesome, Mège-Mouries’s beef-fat-based spread was certainly cheap—and that became a problem.

Soon, margarine came to America, where it was marketed as an inexpensive butter substitute, occasionally called “butterine.” Commercial dairies felt threatened by the prospect of people mistaking oleomargarine for butter or choosing it instead of butter. They had good reason to be scared: unscrupulous retailers often sold the stuff as butter. As an 1877 New York Times article reported:

Christopher Strauss, grocer, of No. 16 Second-avenue, was arraigned before Justice Murray in the Fifty-seventh Street Police Court yesterday charged with selling oleomargarine, representing it to be pure butter. S.A. Churchill, a former manufacturer of the artificial article, and who is now employed as a detective by the Butter and Cheese Exchange, appeared as complainant.

But the butter and cheese detectives could only do so much. As Chris Burns puts it in “Bogus Butter,” his invaluable masters’ thesis about Gilded Age margarine legislation, by 1886, “estimates of ‘bogus butter’ on the market in the previous year were 60 million pounds, most of it fraudulently sold as butter.” The dairies feared the rise of a cheap, oily dystopia, and they decided to take action.

Big Butter lobbied legislatures to heavily regulate margarine—how it could look, where it could be sold—and, in 1886, Congress passed the Oleomargarine Act, which imposed special taxes on margarine and margarine dealers. Around the same time, the butter interests lobbied state legislatures to pass laws preventing margarine manufacturers from dyeing their product to resemble butter; instead, it had to be sold in its unappetizing natural color, white. In its 1894 decision on Plumley v. Massachusetts, the Supreme Court went so far as to rule that colored margarine could not be transported across state lines into a state with a colored-margarine ban.

Simultaneously, butter partisans spread rumors that oleomargarine was unfit for human consumption. According to Chris Burns, the congressional debate over the Oleomargarine Act was particularly fierce in this regard, with congressmen deriding margarine as unhealthful witchery and urging their colleagues to take action against “the application of chemical fluids and compounds in transforming a mass of loathsome and unwholesome ingredients into an article of food at a trifling cost.” As congressman Albert Burleson would later put it, “never in the history of the world has a food product been so persistently and outrageously misrepresented as oleomargarine.”

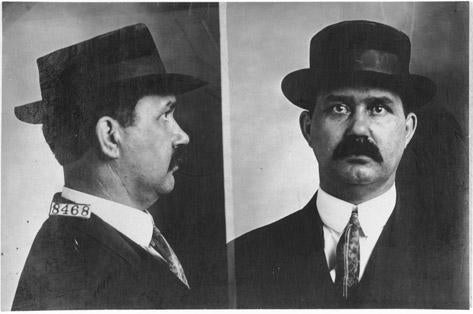

The taxes and legislation had the desired effect: margarine production decreased, according to Burns. But, even after all this, people still wanted margarine, and in the best entrepreneurial tradition, bootleggers stepped in to meet the demand, producing a tax-free, pleasantly colored product for a grateful public. As Katherine Mangu-Ward reported in a 2011 Reason article, at least four men—Charles Wille, John L. McMonigle, and brothers Joseph and Toney Wirth—served time in Leavenworth for margarine bootlegging; the persistent McMonigle served two separate stints, first in 1913 and then again in 1915. History books are sadly bereft of first-hand accounts of the black market margarine trade, but I like to imagine these bootleggers as plump, sweaty fellows who cramped up whenever they had to run from the law.

Over time, margarine use became relatively normalized. “My own experience with this product is of the most satisfactory sort,” wrote Prof. W.O. Hedrick of the Michigan Agricultural College in 1925. “I have no doubt that there are many people for whom butter is inaccessible at all times, and I see no reason why they should not be allowed to use margarine.” In 1950, most of the restrictions on margarine were lifted when President Harry Truman signed the Margarine Act of 1950, repealing the 1886 legislation. Today, faux butter can assume any color you’d like, and the margarine trade is a healthy and respectable business, with the United States’ top brand, I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter!, selling more than $200 million worth of product in 2011. But personally, I prefer to buy my margarine from a guy in the alley down the street, who hands it over in a brown paper bag as we both nod furtively. It’s the American way.