Crime is Slate’s crime blog. Like us on Facebook, and follow us on Twitter @slatecrime.

It’s been just over a year since Sanford, Fla., neighborhood watch volunteer George Zimmerman shot and killed teenager Trayvon Martin, and the case remains as divisive and confounding as ever. Zimmerman claimed that he only fired after Martin initiated a physical confrontation. Early on, he avoided arrest thanks to Florida’s “stand your ground” law, which requires police to show probable cause that a suspect used unlawful force. Here’s the relevant part of Florida’s statute:

A person who is not engaged in an unlawful activity and who is attacked in any other place where he or she has a right to be has no duty to retreat and has the right to stand his or her ground and meet force with force, including deadly force if he or she reasonably believes it is necessary to do so to prevent death or great bodily harm to himself or herself or another or to prevent the commission of a forcible felony.(Emphasis is ours.)

Stand your ground didn’t protect Zimmerman forever: He was ultimately arrested and charged with second-degree murder after a special prosecutor was appointed to oversee the case. Zimmerman’s defense team has also indicated recently that it’s unlikely he’ll rely on a stand-your-ground defense at trial. Even so, the controversial law has continued to be a lightning rod, leading Florida Gov. Rick Scott to convene a bipartisan, multi-racial task force to study the legislation.

Last week, the task force issued its final report, which essentially concluded that stand your ground was fine as is. The report made several minor recommendations, some of which seemed like specific responses to the Martin case—that the legislature should clarify that neighborhood watch participants are not actually supposed to confront potential suspects, for example—but ultimately found that “all persons who are conducting themselves in a lawful manner have a fundamental right to stand their ground and defend themselves from attack with proportionate force in every place they have a lawful right to be.”

There is a lot of common-sense support for the notion that a person shouldn’t be found guilty of a crime if they act in self-defense. Stand your ground, though, is generally invoked in the early stages of a case, either in the hope that the cops won’t make an arrest or that a judge won’t let it go to trial.

People pleading self-defense generally must show that they made every possible effort to avoid violence. That includes retreating, except in the case where they’re in their home—an old common-law principle known as the “castle doctrine.” Stand your ground maintains that the world is your castle and that, if you’re feeling threatened, you are under no obligation to retreat before fighting back.

The main conceptual difference between self-defense and stand your ground is that the former presumes a lawful society while the latter imagines a society under siege. I’ve stood in line at Walt Disney World, and so I get why Floridians might think that anarchy rules their streets. But regardless, stand your ground is an odd and dangerous law, primarily because it is so vague. There’s no absolute standard for determining that you are in danger of death or great bodily harm, and the law seems likely to encourage paranoiacs to misread and escalate anodyne situations. This is the reason why we rely on paid police officers to defend us, rather than arming a bunch of jittery citizens and telling them to use their best judgment.

Moreover, I think the law encourages people to conflate the right to meet force with force with the obligation to meet force with force. If you’re riding a city bus and a drunk guy tries to push past the bus driver without paying his fare, then, under stand your ground, you’d perhaps be technically justified in assaulting the guy. You had a right to be there. The drunk guy was using force. I’ll take my key to the city, please!

Sure, this seems outlandish—until you read about some of the actual situations where stand your ground has been invoked. Take the case of Michael Dunn, a white man who fired a pistol into an SUV filled with black teenagers in a Jacksonville parking lot, killing 17-year-old Jordan Davis. Though the confrontation began when Dunn asked Davis and company to turn down their music, Dunn claimed that he only fired after the car’s occupants menaced him with a shotgun. Police have found no evidence that the occupants were armed. Dunn is expected to invoke stand your ground.

What the Dunn case shows is that stand your ground can give people tacit permission to be more reckless and confrontational than they otherwise might. It’s strange that some Florida lawmakers don’t see this as a problem. Over the past few months, according to the Orlando Sentinel, Florida state legislators have introduced several bills designed to amend the law. Some of those bills aim to dial the law back; some don’t. The latest, introduced this week by Republican Neil Combee, would extend stand your ground protections to people who fire warning shots or brandish weapons in the hope of scaring away potential attackers.

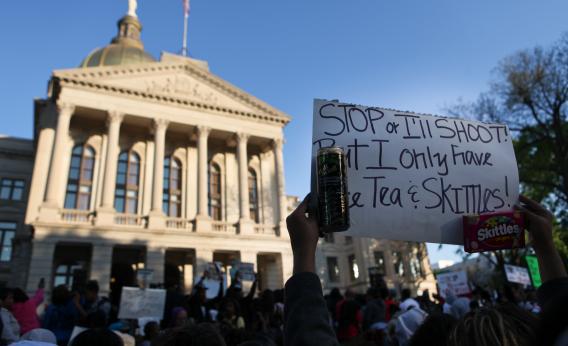

I don’t buy the argument that the world will be safer when people are allowed to pop off a round whenever they spot trouble in their rear-view mirrors. And I disagree with the idea that law-abiding citizens shouldn’t ever have to retreat in the face of danger. The real world is not a Death Wish movie. It does not need more hyper-aggressive vigilantes who see it as their responsibility to take back the streets. George Zimmerman felt threatened by a stranger, so he shot and killed Trayvon Martin, who was armed with a can of tea and a bag of Skittles. A little more than a year later, I’m standing my ground: There should not be a law that allows someone who behaved like Zimmerman to avoid standing trial for his actions.