Crime is Slate’s crime blog. Like us on Facebook, and follow us on Twitter @slatecrime.

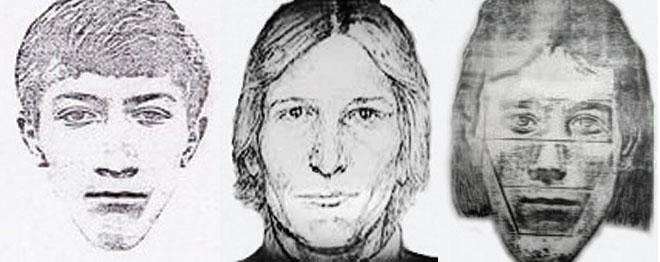

If you’re diligent enough, you can use the Internet to find just about anything: a good job, a bug-free used mattress, a roommate who will let you drink all his beer. But how about a long-dormant serial killer? Los Angeles magazine just published a good story about a group of amateur online detectives who have become obsessed with identifying a man suspected of committing 50 sexual assaults and 10 murders across California in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The police call him EAR/ONS—a clumsy combination of “East Area Rapist” and “Original Night Stalker” that sounds less like the name of a fearsome killer than of a jewelry manufacturer. The article’s author, Michelle McNamara, proposes a better monicker: the Golden State Killer.

McNamara, a blogger and freelance writer, is one of the many homemade criminologists who spend their free time scouring the Internet, trying to solve cold cases. “By day I’m a 42-year-old stay-at-home mom with a sensible haircut and Goldfish crackers lining my purse,” she writes. “In the evening, however, I’m something of a DIY detective.” Many of these DIY detectives congregate at the online message boards for a television show called Cold Case Files, an A+E program that was cancelled in 2006. Others flock to The Doe Network (“There is no time limit to solving a mystery”), a website devoted to identifying missing persons and investigating cold cases, or another site called websleuths.com. While their methods may be unorthodox, they occasionally get results—the Doe Network claims that its members have solved or helped solve more than 66 cases, most recently helping to identify the remains of Peggy Sue Houser, who went missing in 1981.

There’s nothing new about amateur detectives. They’re everywhere in fiction: Sherlock Holmes, Miss Marple, the kid from Cop and a Half. The real-life Vidocq Society is a mystery-solving club comprised of prosecutors, coroners, criminal profilers, and other subject-matter experts; they’ve helped solve numerous cold cases over the club’s 23-year history. The common thread here is that the amateurs are somehow smarter or more perceptive than their professional counterparts. That’s the value-add.

From what I can tell, most Internet sleuths aren’t trained investigators or preternaturally perceptive polymaths; they’re just homebodies with a lot of time on their hands. There are “a spectrum of personality types on the message board,” writes McNamara, “from paranoid cranks to the raw, curious insomniacs driven by the same compulsion to piece together the puzzle as I am.” Their value-add, in other words, is diligence, the patience and commitment needed to investigate every potential lead, no matter how seemingly irrelevant. They do the tasks that actual investigators could never do, either because they lack the time or because the tasks make no sense.

McNamara writes about “tracking down every detail I could about a member of the 1972 Rio Americano High School water polo team, because in the yearbook photo he appeared lean and to have big calves, maybe the same big calves that the Golden State Killer’s earlier victims had identified.” She mentions a message-board member she calls “The Kid,” who has “spent 4,000 hours scouring everything from old directories to yearbooks to online data aggregators” in order to assemble a 118-page, 2,000-name-strong “master list” of possible suspects. Another woman, dubbed “the Social Worker,” once invited a potential suspect out to dinner, and then swiped his water bottle for DNA testing. Eat your heart out, kid from Cop and a Half.

You can see how all this effort might have some value. You can also see how it might be incredibly annoying to legitimate investigators. McNamara mentions one “agitator” who recently visited the message board and compared its members to Walter Mitty, the James Thurber character who compensates for his humdrum life by inventing an elaborate fantasy world. McNamara doesn’t take any offense. “By then I was convinced one of the Mittys was probably going to solve this thing,” she writes.

Her article, however, isn’t very convincing on that point. The amateur sleuths on the Golden State Killer’s trail come across as harmless at best and frustratingly incompetent at worst. Their leads never seem to pan out. The story opens with McNamara online late one night, elated to have located a pair of cufflinks she believes the killer may have taken from one of his victims in 1977. “I bought them immediately, paying $40 for overnight delivery, and went to wake my husband. ‘I think I found him,’ I said.” She was wrong.

“What drew us to this mystery,” writes McNamara, “was that it can be solved.” But the best new evidence mentioned in the story—a hand-drawn map the Golden State Killer may have left at a crime scene in 1978—has nothing whatsoever to do with the message board community. Instead, investigators found it stored away in a police property room. That map is now up on the Los Angeles website, alongside a bunch of other data pertaining to the case—a timeline of the killer’s crimes, a sample of his handwriting, an ostensible voice recording—in hopes of maybe crowdsourcing a solution.

It might work. While I doubt that any of these online detectives will solve the case on their own, it’s possible that something good may come from presenting this material to a broader audience. Call it the America’s Most Wanted strategy. Cold cases go cold for lack of resources, evidence, and interest. Online detectives can help somewhat with the first two. But perhaps they do the most good by stoking public and professional interest in cases that might otherwise go forgotten.