On Aug. 1, 1966, an ex-Marine named Charles Whitman packed a half-dozen guns into a military-issue foot locker, lugged it to the observation deck of a 28-story tower on the campus of the University of Texas at Austin, and opened fire on the pedestrians below. By the end of the day, 16 people (including Whitman’s wife and mother, whom he had killed that morning) were dead and more than 30 were wounded in what still stands as one of America’s deadliest school shootings. The Whitman massacre introduced a generation to the horrors of domestic terrorism. It also inspired one of the most baffling songs in the folk-rock canon.

Now and then I’d like to use this space to revisit and analyze various crime-related ballads. There is no better song to start with than “Sniper,” Harry Chapin’s creepily sentimental, you-are-there retelling of the Whitman shootings. The nine-minute-plus tune, released in 1972, stands with “Timothy” and “Disco Duck” as one of the most-disturbing songs of the 1970s.

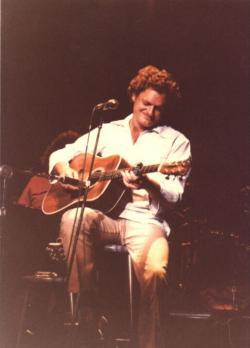

Harry Chapin specialized in ponderous, sentimental story-songs about everyday people—nostalgic cab drivers, small-town dry cleaners, loveless diner waitresses. He was my absolute favorite singer in childhood, back when I was too young to appreciate things like subtlety and restraint. “No singer/songwriter, not even Rod McKuen, apotheosizes romantic self-pity with such shameless vulgarity,” wrote Stephen Holden in Rolling Stone, and he was basically right. In Harry Chapin’s songs, failure is almost always noble, clichés almost always count as wisdom, and people whom the world considers delusional are almost always the sanest ones of all.

Charles Whitman, perversely enough, is a textbook Harry Chapin hero. Though he was tall and athletic physically, Whitman was a little man emotionally. According to A Sniper in the Tower, Gary M. Lavergne’s 1997 book about the shooting, Whitman was insecure about his abilities and ashamed of what he deemed his limited accomplishments. He was the sort of person who collected motivational sayings, and repeated them to himself every morning. While in the Marines, Whitman carried a card bearing a phrase that would become a personal motto: “YESTERDAY IS NOT MINE TO RECOVER, BUT TOMORROW IS MINE TO LOSE. I AM RESOLVED THAT I SHALL WIN THE TOMORROWS BEFORE ME!!!” Set that phrase to music, and one could easily mistake it for something written by Chapin himself.

Though Chapin never comes out and says that “Sniper” is about Whitman, it’s clear he was inspired by the University of Texas shooting. The song begins with the nameless protagonist walking toward a campus tower, carrying two suitcases. (While Chapin doesn’t immediately tell us what this character is up to, the fact that the song is called “Sniper” sort of undercuts the suspense.) Then, changing tempos, Chapin cuts to the perspective of the sniper’s acquaintances being interviewed after the shooting. “I didn’t really know him. He was kind of strange,” Chapin sings. “Always sort of sat there. He never seemed to change.”

And yet Charles Whitman wasn’t an outcast. An Eagle Scout and married man, the well-liked Whitman has consistently been described as an “all-American boy.” Indeed, after the shooting, Whitman’s father-in-law noted that Whitman was “just as normal as anybody I ever knew, and he worked awfully hard at his grades. There was nothing wrong with him that I knew of.”

But by no means was he happy. Whitman abused Dexedrine, and he suffered from incessant and painful headaches. He hated his father, a stern, self-made man whom Whitman was always trying (and failing) to please. After stabbing his mother to death on the morning of Aug. 1, Whitman penned a letter that authorities would find later. “The intense hatred I feel for my father is beyond description. My mother gave that man the 25 best years of her life,” Whitman wrote, explaining that he had killed his mother to ease her suffering. “He has chosen to treat her like a slut that you would bed down with, accept her favors and then throw a pittance in return.”

Throughout the song, Chapin cuts back to other interviewees, all of whom admit that they never paid much attention to the sniper in life. Eventually, you start to suspect that Chapin regards them as the true monsters. This shouldn’t have surprised anyone familiar with Chapin’s work. Again and again, he shows disdain for those who fail to pay attention to the “little people”—the busy father in “Cat’s in the Cradle,” the sneering music critics in “Mr. Tanner.” (Perhaps the critically reviled Chapin was simply projecting his own frustrations.) Listen to his albums, and you’ll come away with the sense that the worst thing that can happen to a human being is to be ignored.

And so it’s no real surprise that “Sniper” really shifts into lunacy when Chapin switches perspectives again and becomes the shooter:

He said Listen, you people, I’ve got a question

You won’t pay attention but I’ll ask anyhow.

I found a way that will get me an answer.

Been waiting to ask you ‘til now.

Right now!

The rest of the song crescendos in anger and intensity, with Chapin gleefully describing the sniper’s kill shots:

The first words he spoke took the town by surprise.

One got Mrs. Gibbons above her right eye.

It blew her through the window wedged her against the door.

Reality poured from her face, staining the floor.

He then concludes—somewhat accurately, as it turns out—that the shooter must have been motivated by mommy issues:

Mama, won’t you nurse me?

Rain me down the sweet milk of your kindness.

Mama, it’s getting worse for me.

Won’t you please make me warm and mindless?

Mama, yes you have cursed me.

I never will forgive you for your blindness.

I hate you!

The critics hated “Sniper.” In Rolling Stone, Holden called it an “incredibly pretentious sub-musical ‘epic’ ” that “must represent some kind of all-time low in tasteless overproduction.”

The critics were wrong. Yes, the lyrics are ungainly. Yes, the song is overproduced. But Chapin’s performance overcomes all these flaws through sheer force of emotion. Throughout his career, he showered his protagonists with pity, but rarely actual empathy. “Sniper” is one of the only songs in which he really connects with his hero—and it’s terrifying.

In a sharp critique of “Sniper” on the website Critics at Large, Kevin Courrier observes that “as he describes Whitman’s moments climbing the tower, his glee at firing the gun, the stunned reports of news reporters and witnesses, Chapin is breathlessly swept away by the rage he’s unleashed in the character.” Courrier praises a bare-bones 1975 Soundstage performance—the one embedded at the top of this post—in which Chapin and his band seemed as if they were inhabited by Whitman’s spirit:

With no trick sound-effects, “Sniper” gets stripped down to just what his ensemble can re-create on stage. Chapin is almost maniacal here, as if determined to take back control of the song. But Whitman possesses him to the point that you can feel Chapin’s band backing away. The audience applauds at the end but likely with relief.

The evening before he climbed the tower, Charles Whitman wrote a goodbye letter. It began: “I don’t really understand myself these days. I am supposed to be an average reasonable and intelligent young man. However, lately (I can’t recall when it started) I have been a victim of many unusual and irrational thoughts.” Afterwards, an autopsy revealed that Whitman suffered from an undiagnosed brain tumor that was growing so rapidly it would’ve killed him before the end of the year. Many people have speculated that the tumor somehow altered Whitman’s personality and prompted the killing spree.

But Gary Lavergne doesn’t buy it. At the end of A Sniper in the Tower, he writes: “Charles Whitman became a killer because he did not respect or admire himself. He knew that in many ways he was nearly everything he despised in others, and he decided that he could not persevere. He climbed the Tower because he wanted to die in a big way; not by suicide, but by taking others with him and making the headlines.”

Harry Chapin more or less reached the same conclusion. The title of the album on which the song appears is Sniper & Other Love Songs, which sounds like a grotesque joke until you realize that Chapin does actually love his Whitman stand-in. Chapin sees his protagonist as just another misbegotten schmoe, motivated by loneliness and the absence of love. In a world that hastens to label its spree killers as monsters and demons, Chapin basically says that mass murder is a function of missed opportunities and deferred dreams, and that it was our fault the sniper pulled that trigger.

I can’t decide if that sentiment is offensive, brave, hideous, or all of them together. But it sticks with me. While writing this piece, I started thinking about the part in Death of a Salesman where Willy Loman’s wife soliloquizes about how “attention must be paid” to the world’s losers. Harry Chapin, who died at age 38 in 1981, built a career around this notion, and “Sniper” comes out and says what the rest of his songs only imply: That ignoring these people is a heinous crime.