This post originally appeared in Business Insider.

Yahoo wants to replace Google as Apple’s default search engine.

At first glance, this sounds crazy—Yahoo doesn’t even have its own search product. It uses Microsoft’s Bing.

So why does Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer think there is even the slightest possibility this might happen?

One possible answer—and the big, big caveat here is that this is purely speculative—is that Google is not as strong in search as its history suggests.

Search, as a business, is becoming a lot more complicated, with a lot more players, and a lot more stuff to be searched. It used to be that the business was simple, in principle: You went to Google’s search box, typed in what you were looking for, and clicked on a link.

But with Facebook, Amazon, and Twitter running their own search operations, and vast new forms of media—music and apps, most obviously—being largely impenetrable to regular search, we may be entering an era in which keyword-matching and link-ranking aren’t good enough anymore.

In that scenario, Google is the bloated incumbent, ripe for disruption by new, leaner, quicker startups that realize search isn’t about your mom sitting with her laptop typing “new shoes” into a text box. It’s about her daughter, who wants her phone to automatically surface relevant new material even before she asks for it.

In this scenario, Google is weak in search.

Sequential Growth Is Getting Worse

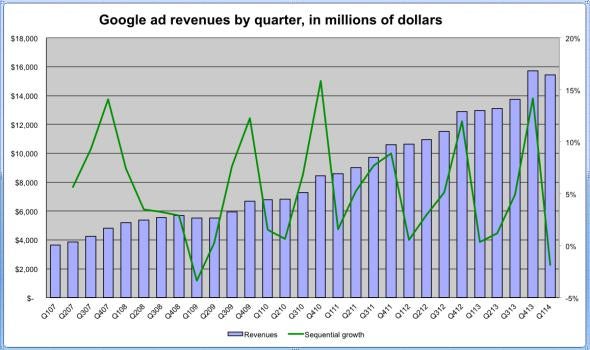

Here’s the economic evidence for the early signs of that weakness (below). Note the green sequential growth line is getting worse, not better:

SEC

Again, before we go any further, let’s underline the obvious: Google is now so massive—$15 billion in revenues per quarter—that its sequential growth is declining simply because it is so big. This isn’t a sign of weakness; it is a sign of massiveness. (This chart excludes the Motorola numbers.)

But … it’s tough to ignore that in this quarter growth was negative. That never used to happen. (It happened once, in Q1 2009, but that was clearly the recession, not Google, thus we shall ignore it.)

The company has an official name for its brief recessionary periods: “deceleration.”

The stock sank 5 percent after hours Wednesday night, when Google revealed its Q1 numbers. It was down another 4 percent Thursday morning. Investors, clearly, are sensing something they don’t like.

Again, here’s the question: Why would a company that has a natural, legal monopoly over search see even temporary declines in its business?

Google Is Weaker in Mobile Than People Think

The short-term answer is that Google’s search business is transitioning to mobile and that the disconnect in supply and demand for mobile search ad clicks is giving Google’s advertisers a temporary bonanza—the price of search is falling, and Google’s revenues are soft because of that. Google is still getting most of the clicks, but it is unable to charge as much as it used to for them.

Wall Street analysts hinted yesterday that they think Google’s mobile search business is weak because it doesn’t have the pricing power it had on desktop. (Average cost-per-click for advertisers declined 9 percent in Q1, and aggregate paid clicks grew by 26 percent—a much lower rate than the 30 percent–plus growth rate Google has historically seen.)

Chief business officer Nikesh Arora was asked about that on the call. He said:

I’ve had firm belief and I continue to hold on to it that I believe in the medium to long term: Mobile pricing has to be better than desktop pricing. And I think the reason—the way to think about it is that in mobile you have location and you have context of individuals which you don’t have on the desktop.

… So part of our challenge has been that if you guys just [had] huge massive advertise[rs] in the desktop which over the last decade have become better at advertising, Understanding, optimization, understanding conversion, understanding [transactions].

That journey is just beginning for advertisers in the mobile site. They’re just beginning to understand what it takes for the end user to come transact on their website [in mobile].

So like right now we can lead the horse to the water, we can’t make it drink.

Arora usually speaks in the vaguest generalities possible. But there he is saying that Google can’t seem to persuade advertises to get with the mobile program: “We can lead the horse to the water, we can’t make it drink.”

Facebook, Apple, and Amazon Are Carving Off Google’s Business

Google’s problem with mobile is that huge chunks of the phone landscape are being carved off by new, upstart search organizations. Amazon, for instance, has a huge mobile shopping search business through its app—and Google has none of that business.

Facebook has its own search engine and will soon add Post Search, the ability search through the trillion or so status updates on Facebook. That search will eventually be backed by Facebook’s artificial intelligence unit.

Search inside Apple’s App Store is one of the most valuable search types there is. It’s already the core of a $16 billion business at Apple. Yet Google search has no view into the App Store.

And Apple is working with Shazam to create a way of recognizing songs and searching for them, presumably in iTunes.

And there are a ton of other smaller, specialized search databases doing all sorts of useful things that don’t want or need Google to be inside them.

From this perspective, Google isn’t strong. It’s weak.

Why Monopolies Go Into Decline

Of course, Google isn’t sitting still for this. Google’s acquisition of DeepMind for between $400 to $500 million is an example: Search backed by true artificial intelligence could put Google ahead of its rivals instantly, if it’s genuinely superior.

But the very fact that it wants to be the search engine for everyone, everywhere, is the source of its weakness: A small company like Shazam that is an expert at recognizing music can devote 100 percent of its attention to that, and become better than Google will ever be at doing the same thing. At Google, music recognition would be one of only a hundred action items on CEO Larry Page’s desk.

In the meantime, Shazam has its little core of advertising clients that are advertising on Shazam’s mobile apps, sucking dollars that might otherwise have gone on mobile search ads in Google.

Which is why it’s so worrying that Google’s Arora is still arguing, two years after the issue first surfaced, that one day, eventually, in the “medium to long term,” its mobile search business will improve.

See also: How Google Botched the Release of Glass