All the President’s Men is famous for its accuracy. Whenever possible, director Alan J. Pakula shot the story of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s Watergate investigation on the locations where the real-life story took place, and when the Washington Post’s newsroom wasn’t available, the production built a meticulous recreation, even importing trash from the Post’s wastebaskets to fill their own.

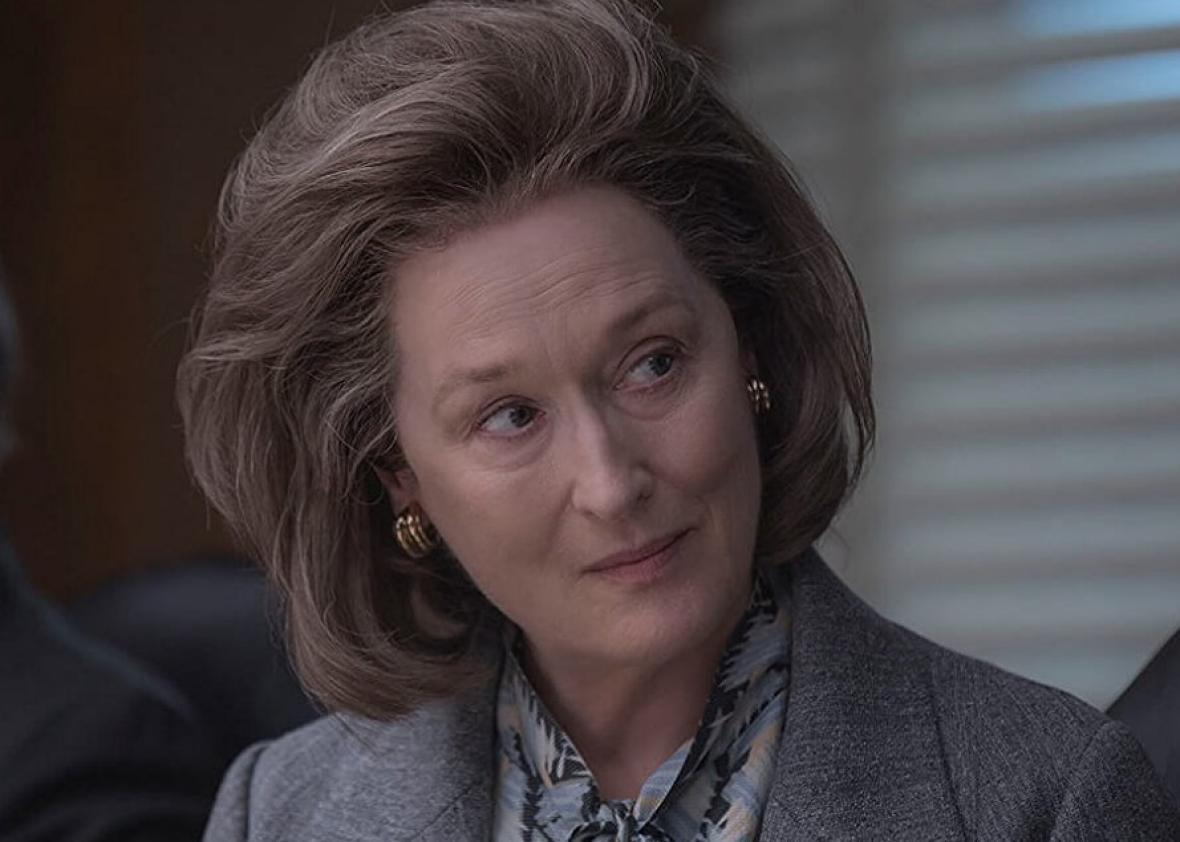

The Post’s publisher, however, wasn’t accorded the same respect as its garbage. For all that it gets right, All the President’s Men steps flagrantly wrong in its treatment—and, frankly, its erasure—of Katharine Graham. But she’s the central figure, played by Meryl Streep, in Steven Spielberg’s new drama The Post: a lesser film, to be sure, but one that does a great to deal to correct the popular perception of this important woman.

Graham was the daughter of Eugene Meyer, who bought the bankrupt Post in 1933 and restored its finances and reputation. Thirteen years later, Meyer retired and handed the reins to Katharine’s husband, Philip Graham, who battled alcoholism and depression even though the paper continued to thrive. When he ended his own life in 1963, Katharine took over, overseeing not only the paper’s turn to profitability but its ascension from local publication to national investigative force—first via their publication of portions of the Pentagon Papers and then by breaking the story of the Watergate burglary and its cover-up.

And yet, Graham is barely represented in the film version of All the President’s Men. She’s never seen, and mentioned only once, in a scene in which Bernstein calls Attorney General John Mitchell for comment, and his furious response includes the growled warning, “Katie Graham’s going to get her tit caught in a big fat wringer if that’s published.” In the next scene, Bradlee decrees that the quote will run, but without the words “her tit,” because “this is a family newspaper.” That, according to the film, is the extent of Graham’s participation in the Watergate investigation.

All the President’s Men was bound to its source material, and Woodward and Bernstein’s book mentions Graham a mere nine times—10 if you count the acknowledgements. But in fact, she was the first person the Post’s managing editor, Howard Simons, called on the morning of June 17, 1972, acting on a tip from Joe Califano (lawyer for both the Post and the Democratic National Committee). He spoke to Graham and not Bradlee that morning—the executive editor, according to Graham’s autobiography, Personal History, “was at his cabin in West Virginia, with a phone that didn’t work”—before calling metropolitan editor Harry Rosenfeld, who called city news editor Barry Sussman, who assigned the story.

From there, Graham writes, it went to Bob Woodward and eventually Carl Bernstein, whose “extraordinary investigative and reporting efforts” she duly credits. But she also adds, carefully, “the cast of characters at the Post who contributed to the story from its inception was considerable.” Graham does not detail her own day-to-day involvement in the story, but in his own book A Good Life, Bradlee does. “Katharine’s support was born during the labor pains that produced the Pentagon Papers,” he writes. “She was coming down before she left almost every night, and generally once or twice more every day. What did ‘we’ have for tomorrow, and what were ‘the boys’ working on for the next day or two?”

He notes, of the ultimate triumph of the story, “We had been supported by the publisher every step of the way, and she had withstood enormous pressures to stand by our side. Pressures from her friends as well as her enemies.” That dramatic element—the stern warnings she received from friends and acquaintances in her Beltway social circle like Nixon’s Secretary of Commerce Peter Peterson, Henry Kissinger, and even John Ehrlichman—is entirely absent from All the President’s Men, as are the public, personal attacks from Republican attack dogs like Senator Bob Dole. (“Oh, you know,” he later told her, “during a campaign they put these things in your hands, and you just read them.”)

The simplest rejoinder to these complaints is that Graham, as an executive, fell outside the purview of the on-the-ground reporting that was the focus of Woodward and Bernstein’s book and its film adaptation. By her own admission, within the time frame covered by the film (its Teletyped postscripts aside, it concludes with Nixon’s second inauguration, in January of 1973), she had “hardly any contact with the reporters.” But even her minimal interactions had juice; in their book, Woodward and Bernstein conclude, of the “big fat wringer” story, “At the Post the next morning, Mrs. Graham asked Bernstein if he had any more messages for her”—a grace note that’s repeated in both Bradlee’s and Graham’s books but not in the movie.

What The Post ultimately dramatizes, and ATPM skips, was the public validation of the paper’s key figure. After the Watergate dam broke, Bradlee writes, “Katharine Graham, God bless her ballsy soul, was going to have the last laugh on all those establishment publishers and owners who had been so condescending to her, and all those Wall Street types turned statesmen who warned her every day that we were going too far.” That conflict gives The Post much of its soul and its substance. It details this powerful woman’s struggle to claim her place among men who don’t even have the courtesy to lower their voices when issuing slags like “Katie throws a great party, but her father gave the paper to her husband”—and eventually her triumph in her field.

The Post has its own accuracy issues—most notably, it overstates Graham’s initial naïveté at the service of her dramatic arc—and a few of its moments of empowerment, like the gaggle of young women gazing upon her visage as she descends the Supreme Court steps, are more than a little corny. But it takes pains to set the record straight about Graham in particular and the place of women in journalism in general, in sharp contrast to ATPM, in which the only women in the newsroom are secretaries and reporters who are only able to help our heroes via their personal/sexual interactions, rather than their investigative acumen.

The Post ends with an homage to ATPM that is the newspaper-movie equivalent of a Marvel post-credits crossover scene. But the dialogue between the films surpasses just explicit echoes. In Bradlee’s book, in the midst of his Watergate chapter, he goes off on a long tangent about Duke Ziebert’s, “an extremely exclusive and sexist club” where he frequently dined with attorney Edward Bennet Williams and columnist Art Buchwald; “Kay would eat with us from time to time,” he writes, but they childishly teased and withdrew the possibility of Graham becoming a member. When she wasn’t there, they would entertain themselves thus: “From time to time during our meals—liberated as we all were—we would play quick games of ‘Wouldya’ as persons of the female persuasion crossed our fields of vision.”

That was the atmosphere in which Katharine Graham was operating, a boys’ club, in which women were either objects of aesthetic gratification or invisible. And perhaps from this distance, that’s the best lens through which to view All the President’s Men: as a contemporaneous example of exactly the kind of casual sexism that Graham battles in The Post and, frankly, battled throughout her life.