Joe Wright’s Darkest Hour is a piece of historical fiction that undertakes a serious historical task: to present Winston Churchill and the British people’s choice to stand up to Hitler as just that … a choice. In hindsight, after eventual victory, the decision to fight against the Germans can appear a foregone conclusion. Since we all like to imagine that we personally would never fold to the Nazis, it can be hard to understand that reasonable people, most of whom had no love for Hitler, seriously considered a truce in spring 1940, during the days depicted in the film. To their eyes, fighting on after the approaching fall of France would only delay the inevitable at the cost of mass civilian slaughter. Better to come to terms now while they still had the leverage of an army and aircraft factories.

However, the film does invent a few details in order to make this very dramatic time even more dramatic. As a British historian who teaches and writes about World War II, I break this all down below.

The decision

In late May 1940, the situation was just as desperate as it is in the film. In the dark, subterranean nerve center where the British War Cabinet assembled, under White Hall in Westminster, bad news constantly flowed in. The Belgians, Danes, and Dutch had been defeated by the Germans. British defenders were nearly beaten in Norway, and France was rapidly collapsing before Blitzkrieg. The British force stationed there was being surrounded, while the French were sorely tempted to make a separate peace with Germany. Meanwhile, the overwhelming majority of Americans wanted no part of Europe’s war, despite Roosevelt’s maneuvering to get the U.S. ready for it. A moving scene from the film depicts the Prime Minister appealing directly to the president, on the edge of begging (though that direct scrambled phone line didn’t exist until 1943).

The real-life sources don’t depict the on-screen shouting matches that occurred in the War Cabinet. It was more that, in some corners, voices emerged suggesting the prudent—horribly regrettable, but from a certain perspective sensible—option of coming to terms with the Germans. Among them were Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden himself, and the ambassador to Australia, whose countrymen would have to do so much of the fighting in this war. A few well-placed German bombs could end Britain’s aircraft industry, and what then? If it turned out that the Germans were willing to leave the British Empire intact, what purpose was served in fighting for an already-defeated Europe? Even Churchill guardedly admitted that he would indeed consider terms offered by Nazi Germany—admitted so behind closed doors.

But the historical sources don’t suggest that Churchill was on the edge of seeking terms, as is hinted at in the film. If the British ultimately had to fight a resistance campaign—on the “hills,” “beaches,” and “landing grounds”—against German occupation, it would be far better that she had never considered capitulation. Beside the moral surrender in such a step, Churchill felt more strongly that Hitler could not be trusted to respect any terms to which the countries might agree.

Churchill’s ride on the London subway

There’s a perfectly fantastical scene in the film in which a doubtful Winston Churchill takes a ride on the Underground in order to commune with “the people.” The good people of London tell him to fight on, that they would never surrender. In the film, this St. Crispin’s Day speech from District line commuters to the Prime Minister steels him for the fight, and all that remains is to tell the Commons that “we will never surrender.”

Would the British people ever have done so? In those disastrous days, might they, say, have supported a snap election and voted in a government ready to make peace with the Germans? It is impossible to know, but George Orwell—a prescient observer if ever there was one—thought it possible. As a journalist observing his fellow Englishmen, he sensed that working people who did not feel represented by the Westminster elite already felt subordinated. Why would it matter if a fascist New Order swept away the plutocratic as embodied by Churchill? Orwell asked an influential newspaper editor whether he thought the public would accept negotiations with the Axis. “Hell’s bells,” the editor replied, “I could dress it up so that they’d think it was the greatest victory in the history of the world.”

It didn’t go that way, but not because District line commuters, to a man, woman, and child, snarled unthinkingly that they would never stop fighting! Historian Richard Toye undertook a massive archival dragnet that found the British did not, in fact, snarl along with Churchill’s speeches. Upon hearing them, some were inspired, many were dubious, and many looked to their family and neighbors to assess what they’d just heard. They didn’t cheer like Minnesota Vikings fans; they, in fact, thought pretty hard about what the speeches meant. This is another heartening example from history: Not only did Britain make the hard choice, they didn’t make it in a fit of rhetoric-induced adrenaline.

His speeches

The same goes for Members of Parliament. In his semi-fantastical memoir of the war years, Churchill offered the version of his late May speech to the 25-member outer cabinet pretty much as depicted in the film. According to the diaries of politician Hugh Dalton, he offered the terrific line, repeated in the film, “if this long island story of ours is to end at last, let it end only when each one of us lies choking in his own blood upon the ground.” Churchill, in his memoir, claims this was followed by a standing ovation.

There’s very good reason to believe that the historic event was very different. Churchill might have spoken the line about choking on blood, but his words, according to Dalton, won him “a murmur of approval round the table.” George Orwell, meanwhile, heard from his editor friend the same thing. Again, this doesn’t diminish the resolve of Churchill or the MPs as much as highlight that they were thinking people who believed they’d invited disaster on their families but still chose to fight with a grim nod, not a ticker-tape parade.

Once he was sure about his decision, and had outflanked Halifax and others in the War Cabinet by appealing straight to the outer cabinet, Churchill sought to convince the Germans that it was set in stone and that invading Britain or bombing it would not repeat the results in France. So, on the fourth of June, 1940, Churchill took the fateful step of absolutely committing Britain to a fight-to-the-death in a speech in the House of Commons (it was not broadcast over radio, as depicted in the film, though many people invented the memory of having heard it). The moment to make the hard choice had come, and the British chose to stand alone—or, more accurately, to stand with the Indian Army.

Churchill at home

Focus Features and Library of Congress

Churchill was a professional politician, but he was also a professional writer. He first made his name with his book on his experiences as an army officer in Sudan in the 1890s. And it was through his work as a war correspondent that he ended up a prisoner of the Boers as a young man, something mentioned in the film. The film has many scenes of him writing and rewriting and sweating over words, which nicely capture an important part of his make-up.

In Darkest Hour, Clementine Churchill is shown upset over the couple’s poor finances. That hews close to the truth, since the Churchills did not have the aristocratic income of those with whom they mixed—certainly not enough to support Winston’s luxurious habits. His writer’s income was strained.

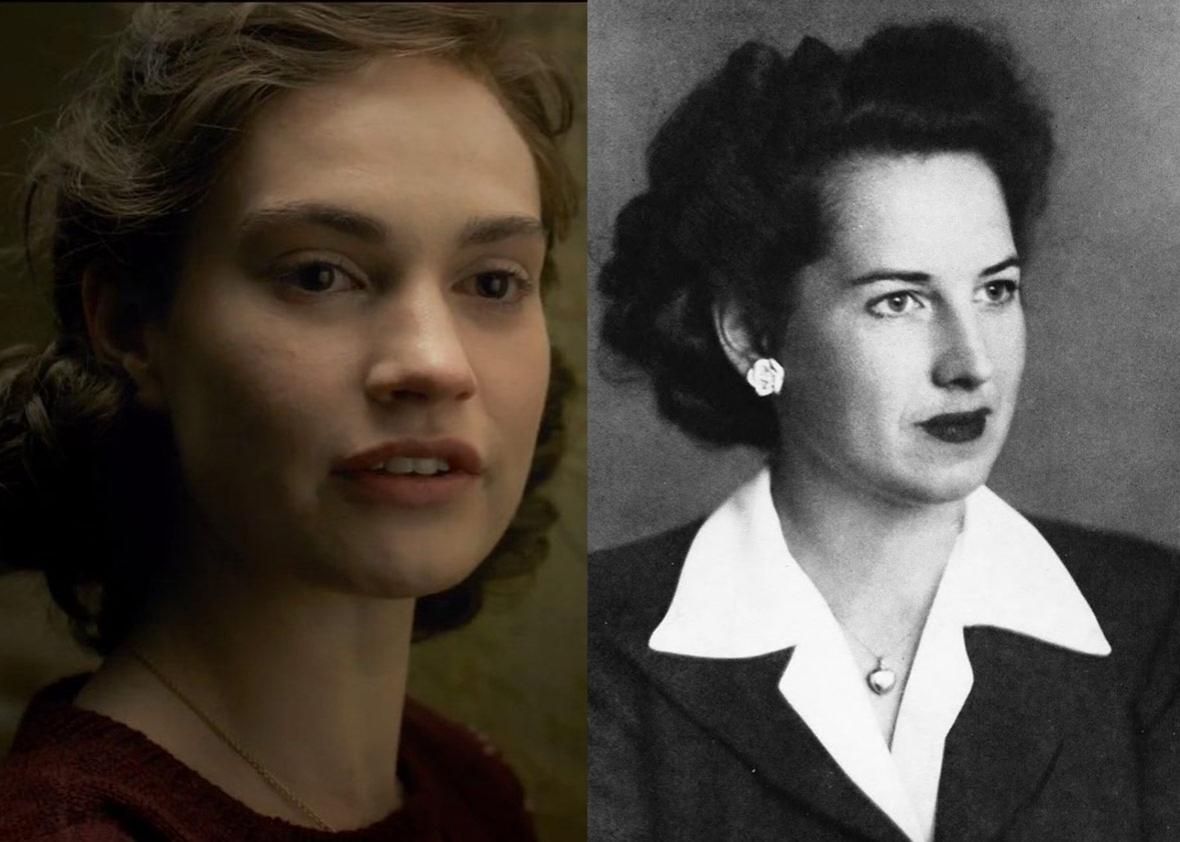

Focus Features and Elizabeth Nel

Clementine also calls Winston insufferable in this scene, and the real-life Elizabeth Layton, his longtime secretary, agreed that Churchill was often exhausting. In her memoir, she called him mercurial, at best, and sometimes simply mean. Yet she became devoted to him. The film does, however, take some liberties with her character. The real Layton was born in South Africa and raised in Canada, so she probably sounded quite a bit different from Lily James. She did not have a brother killed in the retreat to Dunkirk. And she began working for the Prime Minister one year after the events of the film.

Was Churchill really a “drunkard” as one of his critics calls him in the film? He seems to always have a glass of Scotch in his hand. In real life, he claimed to always have it precisely watered down, whereas in the film he seems to drink it neat. So while he wasn’t a drunkard, Churchill seemed to have been a high-functioning alcoholic who self-medicated throughout his days.

Churchill’s opponents

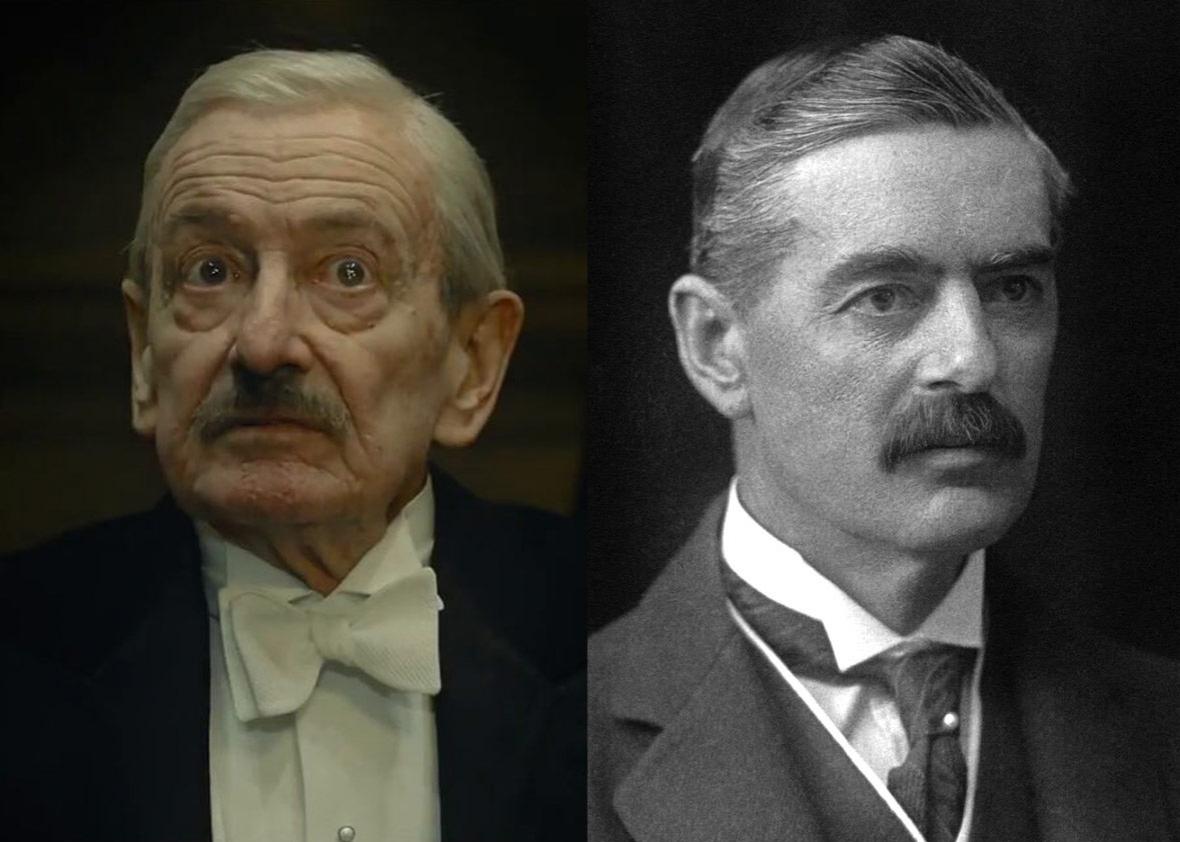

Focus Features and Walter Stoneman

There’s no conclusive evidence to suggest that Lord Halifax and Neville Chamberlain were making concrete maneuvers to hold an imminent vote of no confidence in Churchill and end his government. The threat was ever-present, certainly, until the British—with utterly requisite service of the Indian Army—started winning some battles in Africa and the Middle East in spring and summer 1941. (After losses to German commander Erwin Rommel in North Africa in late spring 1942, on the other hand, he had to beat back a serious “no confidence” motion.)

Was Churchill really that doubted and suspected by his fellow MPs, even fellow Tories? Yes, he certainly was. The film correctly depicts them suspecting he was a sort of “brilliant failure,” better at words than deeds. The man behind the bloody Gallipoli debacle, the backer of the abdicated king, the son of a madman. He literally embarrassed MPs around him with his emotionality. They feared him for being invariably pugnacious, that his answer to everything was to fight. The filmmakers might also have cited his disastrous attempt to reverse the Bolshevik Revolution at the end of WWI with the failed 1919 invasion of Russia at the cost of hundreds of British lives.

Churchill and the King

Focus Features and Library of Congress.

Sources such as King George VI’s diary suggest his relationship with Churchill did seem to get off to the awkward start depicted on film. The King, who truly was a strong Chamberlain supporter, saw the same baggage everyone else did in Churchill. George (or “Bertie”) had also watched Churchill completely misplay the politics around his brother King Edward’s marriage and abdication. Churchill, meanwhile, had to find a way to be deferential to the King while not yielding on his commitment to be aggressive.

The same sources also suggest that King George grew to respect and genuinely like Churchill. Churchill always remained devoted to the King.

It’s true that many recommended the King and his family flee Britain for Canada, but he decided to stay. When the Blitz started in later 1940, Buckingham Palace was repeatedly bombed. Many of those weekly lunches between the two men who supported each other took place in the palace bomb shelter.

What the movie leaves out

So, the film embodies a good historical lesson, while veering from the historical sources. Besides NFL-style shouting and an imaginary tube ride, where else does it veer?

It’s worth remembering that Churchill opposed Nazism as thuggery, as naked expansionism, even a “soul-destroying tyranny,” as he said in his first radio broadcast as Prime Minister. But Churchill doesn’t get high marks as a democrat. That’s because he was committed to preserving the British Empire, regardless of what the people who lived there thought. This didn’t endear him or the British to many U.S. observers. And it certainly didn’t endear him to many Indian observers—most of India’s politicians, including Gandhi, called for Indians to sit the war out.

This enraged Churchill, who expected India to get in line. Lucky for Churchill, the professionals of the Indian Army went where they were told. They had already made their choice to make their livings and provide their families welfare as soldiers. Also, many of those soldiers and other Indian contributors to the war effort believed there was an unspoken quid pro quo in the offing: pull Britain’s feet from the fire in exchange for eventual home rule. So, like Churchill, they made a difficult decision of their own.