Just a few days after the New York Times Weinstein story broke last month, a couple of prominent Hollywood men joined the groundswell of women’s voices who shared sickening stories of alleged sexual harassment and abuse, including Brooklyn Nine-Nine star Terry Crews. In a series of Tweets, he described in detail an incident from last year in which a “high level Hollywood executive … groped [his privates]” in front of his wife while at a Hollywood party.

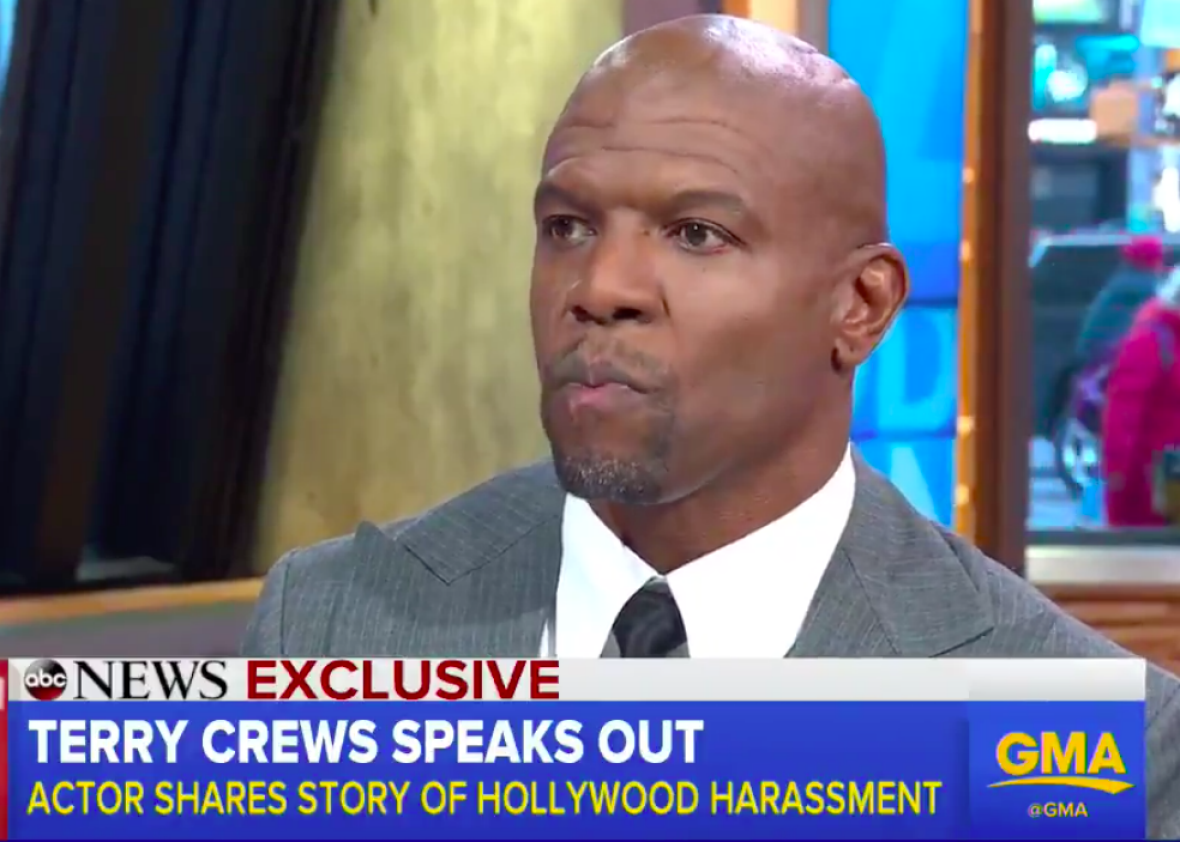

Last week, Crews filed a police report with the LAPD over the alleged assault, and Variety reported that “sources close to the situation” said Adam Venit, the head of talent agency William Morris Endeavor’s motion picture group, was the accused. (Venit is currently on leave from WME pending an internal investigation; his reprsentatives for Venit, WME, and Crews all declined comment to Variety.) On Wednesday morning, Crews gave his first television interview about the story to Good Morning America, revisiting many of the same details he discussed on Twitter (and more), and this time naming Venit. As the conversation with host Michael Strahan began, he laid out just how powerful Venit is in the business—his clients include Adam Sandler, Eddie Murphy, and Sylvester Stallone—and explained that prior to the Hollywood function he attended last year, he had never had any interactions with him.

Crews went on to allege that at the party, Venit kept staring and “sticking his tongue out” at him in an “overtly sexual manner” amidst the crowd of guests, and then groped his genitals. Crews described jumping back, bewildered, and asking him what he was doing, but Venit allegedly repeated the actions until he finally pushed him away and into the other guests around him. The actor said he then went to Sandler, who was nearby, and told him what happened, and to “Come get your boy.” He added that Sandler seemed as stunned as he was: “It was bizarre to both of us.”

The interview feels notable particularly as it highlights how Crews’ alleged experience both overlaps with and sharply veers from the accounts of many of the other women who have come forward during this month-long period of Weinstein fallout. Echoing the stories of Ashley Judd, Gwyneth Paltrow, Lupita Nyong’o, and many more, he unpacks why, almost two years later, he’s only coming forward about this now, describing Hollywood as a culture that encourages “abuse of power” and stressing the huge power imbalance he was faced with in this situation. “[Venit] looked at me in the end, as if ‘Who’s going to believe you?’” the actor told Strahan. Crews said he felt empowered by the Weinstein allegations because he felt he would finally be believed.

Like those other women (and other men, in the weeks since), his silence was operating from a mode of fear—fear of not being believed, fear for the potential professional repercussions. But as a man, and especially a black man, there are other layers of fear that affected him as well, as he distinctly pointed out, on Twitter and in this conversation—the concern that, had he physically lashed out at Venit (“I felt like I could punch a hole in his head,” said Crews), he would have faced a public historically primed to view someone like him as a monster. “The one thing I knew—being a large African-American man in America—I would immediately be seen as a thug. But I’m not a thug, I’m an artist.” (Interestingly, Crews told Strahan that his wife had warned him previously that “something like this would happen” as a way of baiting him into a PR disaster.)

It’s also telling, though not surprising, that Crews’ instinctual response to Venit’s alleged actions was a feeling of “rage” and the desire to physically retaliate. Most, if not all, of the women who have come forward did not describe having such feelings in the moments of their accounts—some, like Ashley Judd, recalled attempting to placate their abusers with a promise in order to escape, or laughing uncomfortably (as some of Louis C.K.’s accusers recounted), or playing along to some extent before finding an excuse to leave. The gender dynamics are inherently different. It would seem that Crews, a former NFL player, might not have possessed a fear for his own personal safety in the same way that the other women did—though he did share their intense sense of feeling violated, which he described as “emasculation.”

Crews’ story displays an intersection of gender and race that hasn’t been as widely talked about in the wake of the Weinstein fallout. Just by unpacking his feelings, Crews helps to both validate other women’s stories and demonstrate how black masculinity like his own can be both exalted in Hollywood and potentially used against him due to racist assumptions. It also emphasizes how women can be targeted differently from men for similar kinds of abuse. In the end, though, Crews shares a sense of relief that so many other women have described now that he’s talking openly: “It freed me.”