Just a few minutes into Netflix’s new documentary Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold, the famously aloof author is finally laid out before us, recalling the start of her 40-year marriage to John Gregory Dunne. “I don’t know what ‘fall in love’ means,” she says, with surprisingly wild gesticulation for such a small woman known for such seemingly placid prose. “That’s not part of my world.”

Yet the movie, the first documentary ever to be made about the elusive author, is all about love, although it’s not Didion’s so much as Griffin Dunne’s, the film’s director and, not incidentally, Didion’s nephew. In a recent interview with the New York Times, Dunne said there was no other way for his film to be: “It was always going to be a love letter. She’s my Aunt Joan.” As a close family member, Dunne was both the only person who could get the access to make this film a reality and the wrong person to make it.

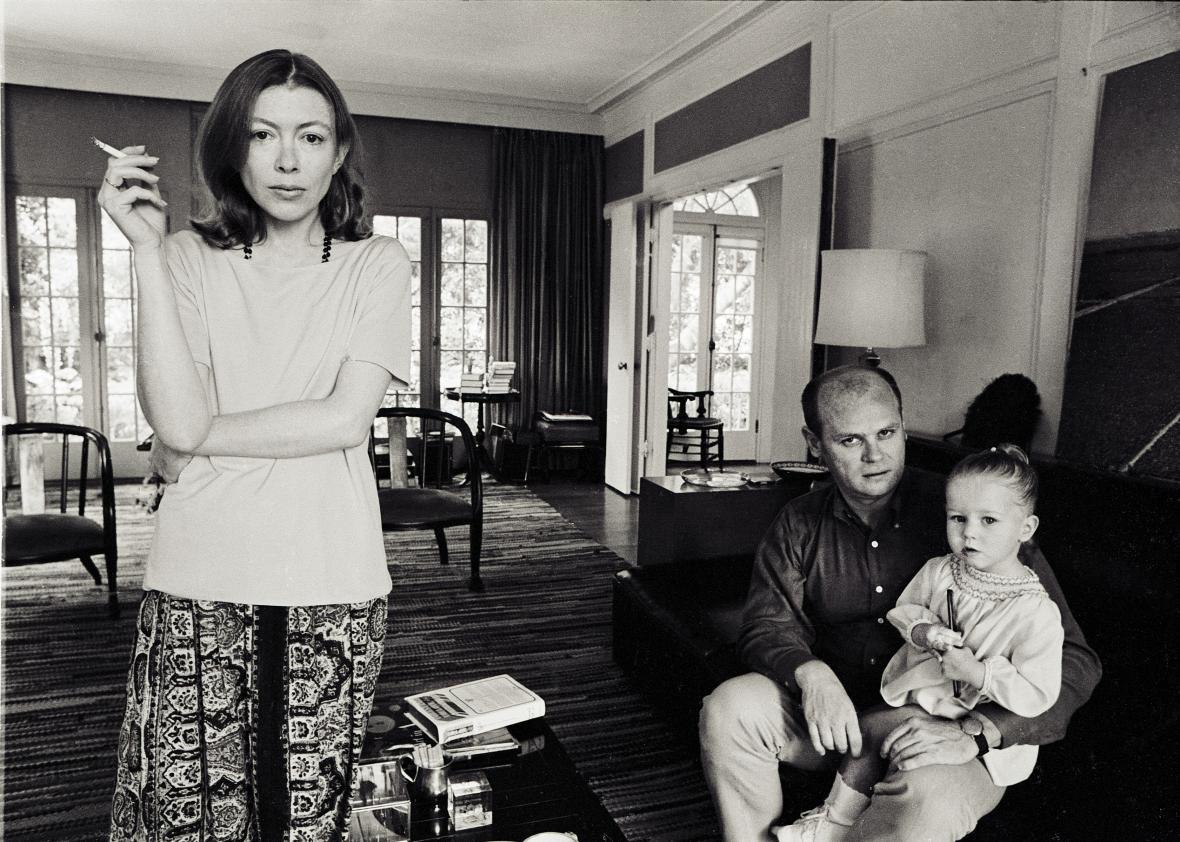

Expectations have been high among Didion fans, who gave more than $200,000 on Kickstarter to get the project going. We want to see her notoriously tiny frame and hear about how she maintained her status as a fashion icon despite so many changing trends. Dunne makes sure those moments are there, giving us time to watch her quick mind calculate and allowing more intimate access, like seeing her crepe-paper hands make a sandwich. But with some of the stickier issues, like what exactly killed Didion’s daughter, Quintana Roo, or what Didion’s life and work can tell us about the present political moment, he can’t always come through. Or perhaps, given his own intimate ties to the subject, he doesn’t want to.

No matter who’s behind the camera—or, for that matter, in front of it—creating a good celebrity documentary is difficult—and while Didion made her fame with the written word, she is a celebrity, with all the cinematographic pull and potential for disenchantment that celebrity implies. Writing about Netflix’s Gaga: Five Foot Two, another documentary about a pipsqueak powerhouse, Amanda Petrusich of the New Yorker reflects:

The problem with a pop star producing a documentary about her life … is that the resulting film often either feels like unapologetic hagiography or is revealing only in extraordinarily calculating ways. (The latter is, of course, more odious.) The accidental tells here—when [Lady] Gaga stops steering her own story or suggests a version that seems to be at odds with the facts—are the most compelling.

While Didion has much less to lose than Gaga from an unflattering portrayal—the author is old and largely free from the tyranny of sales—she is still among the world’s most celebrated memoirists and therefore maintains a steely grip on the details of her biography. The challenge for The Center Will Not Hold, then, wasn’t to convince Didion to spill all of her secrets; she’s already published books about nearly every aspect of her life, including the grief she felt over the loss of her husband and the guilt she experienced after the death of her daughter. The film’s—Dunne’s—job was to push past the coy, calculated prose in which those secrets have been packaged in and their packager’s marble facade.

There are flashes of insight and a few refreshingly candid beats. Sometimes, Didion is persuaded to speak plainly, even caustically. And Dunne is willing to subtly use her own words against her. One such moment stems from their conversation about her seminal book of essays, Slouching Towards Bethlehem. In an archival interview played over old black-and-white family photos, Didion talks softly about how hard it was to leave her 2-year-old to cover the damaged, runaway “flower children” living in San Francisco in the 1960s. A disturbing passage from the book, about Didion witnessing a 5-year-old on acid, is then read aloud. It is a solemn affair. But back in the present, after an arm-waving pause, Didion says forcefully, “It was gold.” There’s even the slightest hint of a smile.

Perhaps that revelation of Didion’s quiet strength is enough. In one of the only truly negative pieces of criticism about Didion, Gawker’s Megan Reynolds (now of Jezebel) argued that Didion’s carefully crafted persona encouraged an entire generation of writers to publicly perform their neuroses, especially the ones that mostly closely reflected the culture of their times. In the process, Reynolds suggests, many writers inspired by Didion erased their strengths, which now seemed inconvenient to the overarching narrative:

Aspiring to the heights of Didion’s delicate flower exterior feels like shooting yourself in the foot. It may seem like vulnerability, but vulnerability requires strength. In Didion, it’s there, but she never chooses to show it. What’s to admire about that?

As a fan of Didion’s work, Reynolds’ piece put me on the defensive. It still does. Everyone projects a persona into the world, writers most of all. Didion’s job, one she did spectacularly well, was to tell stories that, while factually true, exclude most extraneous details. When you’re writing about what feels like the end of the world, the one thing that did make you smile that day probably isn’t worth writing down.

But it seems Reynolds and others skeptical of Didion’s persona get to have the last laugh: While Didion’s work has been firmly canonized, it seems there is indeed a modicum of deception at its heart. The Center Will Not Hold makes clear that while Didion’s published works were carefully deconstructing other people’s myths, she was busy crafting her own. What’s strange is that Dunne seems to know this about his beloved “Aunt Joan,” but continues to prop up her image up and push it along. Is that love?