The cover of the latest issue of the New Yorker depicts President Trump as a sinister clown with razor-sharp teeth leaning out from behind a tree in a dark forest. He’s not exactly Pennywise the Dancing Clown from It—the makeup is wrong, as are the stripes, and the artist, Carter Goodrich, didn’t mention It when he discussed the cover—but the teeth are pretty distinctive, and the pose echoes a widely circulated promotional picture of the latest film’s Pennywise closely enough that it will be the first thing most people think of when they see it. See, for instance, this tweet from California’s Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom:

Or really, see any tweet sharing the cover: Like a lot of recent New Yorker covers, this one seems to be aiming to go viral. It’s topical, designed to provoke a chuckle rather than a laugh, tailor-made for the #Resist hashtag, and more than a little muddled: Pennywise lives in the sewer, not the forest; the scary forest clowns of 2016 didn’t have sharp teeth; and Trump-Pennywise jokes are so ancient, in internet years, that there’s already a meme generator to build your own.

imgflip.com

It’s been that kind of year on the cover of the New Yorker. Before the Trump cover, the magazine devoted covers to gun control, North Korea, the Women’s March, Trump, Trump, Trump, Trump, Trump, Trump, the Statue of Liberty with its flame snuffed out, and an astonishing image that somehow combines Jeff Sessions, James Comey, and that poor guy who got dragged off a United Airlines flight. This is a long way from the covers from the magazine’s early years, which generally steered clear of political commentary in favor of gorgeously drawn slices of New York life. The magazine still runs that kind of cover—Goodrich is responsible for some lovely examples—but the increasing focus on timely-but-toothless political commentary of late is doing Borowitz-level damage.

This transition to thirsty covers isn’t subjective, or some kind of an optical illusion caused by Donald Trump poisoning the culture: There’s hard data to back it up. Using the scientific definition of “a thirsty New Yorker cover” (“a New Yorker cover that sends an incoherent or preaching-to-the-choir political message in a calculated, highly shareable way, especially through pop culture references”—it’s awkwardly phrased, but you know how scientists are), I analyzed every New Yorker cover from 2017, 2016, and 2015 (the Trump era, an election year, the Before Times), carefully measuring each cover’s thirst levels with a combination of hygrometers, barometers, glucometers, and a massive parallel array of Laff-O-Meters. As a control group, I also looked at 1945—a pretty busy year in world history. The results were shocking.

In 2015, the New Yorker published 47 issues (the date on the cover rather than the street date is used throughout). Ten of those issues—from “Clinton’s Emoji” to “Shopping Days” measured well above the FDA thresholds for thirstiness, and one featured a drawing of Donald Trump. (He’s mentioned in another cover, in which Kanye West recreates the “Dewey Defeats Truman” photo but does not appear in person.) This yields a baseline Thirst Ratio of 21.28 percent, and a healthy Trump Ratio of 2.13 percent. By 2016, the Thirst Ratio had risen to 36.17 percent, and the Trump Ratio was at a dangerous 12.77 percent. In 2017, the New Yorker is on track for a Trump Ratio of 15 percent and a Thirst Ratio of an astonishing 42.5 percent. By comparison, the New Yorker of 1945 had only two issues that even came close to being thirsty: one celebrating the liberation of the concentration camps and another that used paper dolls to salute soldiers returning to civilian life. That’s a Thirst Ratio of 3.85 percent, and a perfect Trump Ratio of 0.0 percent. The New Yorker’s current rate of growth in thirst levels is both historically unprecedented and completely unsustainable.

Slate’s Ben Mathis-Lilley and Leah Finnegan at the Outline have both ably diagnosed the root problem here: As an institution, the New Yorker is really, really bad at this kind of comedy. And as the data show, it is inexplicably focusing on it, at a rate that, left unchecked, will surely bring the magazine to wrack and ruin. But how did we get here? And who’s to blame?

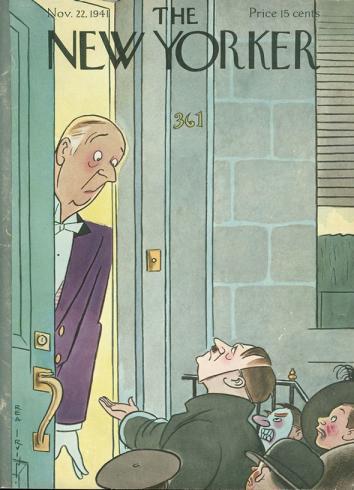

It turns out it’s Hitler. He was the first recognizable world leader to appear on the cover only by accident—an earlier cover showing Hoover giving Roosevelt serious side-eye was pulled after an assassination attempt*—and thus has the dubious honor of being the earliest example of the specific kind of topicality the editors have been chasing lately. (Which is not to say that early covers didn’t have a political agenda, even if it went unspoken—some of the racial stereotypes on display, for instance, are pretty alarming.) But I believe I’ve pinpointed the moment it all went wrong—Nov. 22, 1941. The battle of Moscow was raging, the Einsatzgruppen were massacring Jews all over Eastern Europe, and the United States was just over two weeks away from entering the war. Here’s the New Yorker cover:

Rea Irvin/The New Yorker

What is even going on here? First of all, it’s late November, not Halloween. Second of all, what is even going on here? A fussy butler answers the door to a group of trick-or-treaters and is horrified to discover, among the usual crew of hobo costumes and an ahead-of-its-time Richard Nixon mask, a kid dressed as Hitler. Is the message that Hitler is so scary, he should be a Halloween costume? That dressing as Hitler for Halloween is (and remains) an awful idea? That the American upper class must reckon with their early complicity with the Nazi regime, because Hitler will surely be calling to collect? That only Hitler would go trick-or-treating in late November? The cover conveys that Hitler is associated with bad, perhaps even spooky things, and that’s about it. You might even call him a dangerous clown.

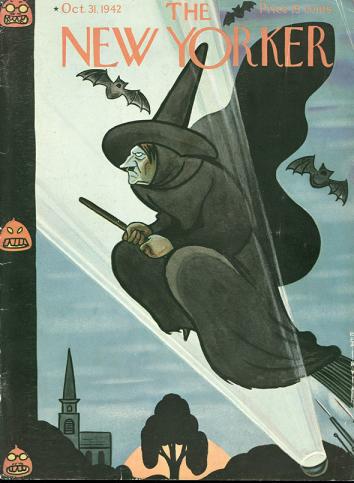

As the war began, New Yorker covers gave life during wartime the same wry gaze they’d previously given peacetime New York City: One cover shows two couples passing on the street as the women, in uniform, salute each other; another turns a maid in a gas mask into some sort of strange insect. But they returned to the kind of weak satire they now seem to specialize in on Halloween of 1942, with this little number:

Rea Irvin/The New Yorker

The message is clearer, anyway: Hitler is bad. Like a witch! Specifically, he’s bad like Margaret Hamilton as the Wicked Witch of the West in 1939’s The Wizard of Oz, making this perhaps the magazine’s first example of the wretched “Remember this thing? Now remember this other thing? SMASHO BASHO!” style of humor that now regularly appears on its covers. Hitler showed up once more after that, in a clever Bayeux Tapestry rendition of D-Day, but then vanished for decades before popping up in the audience of The Producers in 2001. Even the Hitler-as-a-witch cover was apparently against editor Harold Ross’ better instincts: New Yorker cartoonist Michael Maslin notes that Ross wrote to Rea Irvin that he had “put through the Halloween cover with Hitler, although it violates my solemn stand about no more specific people on covers.” And that’s the way things stayed for years, until they didn’t, and now here we all are, watching James Comey get dragged off a plane.

There are a lot of factors to blame for the current dispensation. The turning point might have been Art Spiegelman’s Feb. 15, 1993, cover of a Hasidic Jew kissing a black woman, about a year and a half after the Crown Heights riot. That cover became news in its own right; so did a 1996 Barry Blitt cover that recreated that famous V-J Day Times Square kiss photo with two male sailors. The rise of walking cartoons like George W. Bush, Sarah Palin, and Donald Trump didn’t help things, and by the time social media came along—crack to the early internet’s cocaine—the magazine already had a dangerous taste for thirsty covers. There’s no shortage of villains here. But the precedent established by the Hitler covers that ran under Harold Ross does seem to have been part of the calculus: In a 2014 article about the magazine’s cover’s shift in tone (2014, before the current hockey-stick curve), Françoise Mouly, art editor since 1993, specifically says she looked back at Ross’ approach for inspiration. But Ross almost never ran the kind of cover the New Yorker routinely sports these days: Hitler made the cover fewer times in his entire lifetime than Trump has just this year. And yet it’s the Hitler covers that are the clearest ancestors of today’s New Yorker. Chalk up another demerit for Adolf Hitler: he’s somehow ruining the New Yorker from beyond the grave.

Admittedly, the New Yorker’s current, fast-response approach has produced at least one iconic image: Mouly and Spiegelman’s black-on-black Sept. 11 cover. But it’s also produced a cover where Bert and Ernie celebrate gay marriage, a cover with St. Peter checking Steve Jobs into heaven on an iPad, and—shades of Halloween Hitler—a Dick Cheney jack-o’-lantern. This is not a fair trade. The New Yorker is still one of the crown jewels of American journalism—read Patrick Radden Keefe’s amazing piece about the Sackler family in the latest issue for proof—and in the past, the covers, too, represented their own venerable tradition in magazine illustration. What’s more, that tradition hasn’t died. You can still find slices of New York life, wry portraits of the city’s inhabitants, and beautiful seasonal streetscapes on the cover of the New Yorker. They’re just hard to see through the haze of thirsty political cartoons. So what’s the goal, exactly? Well, Mouly explained what she was trying to do in a 2012 interview with Imprint:

What I’m really looking for are ideas that come from the artists on topics that will give us a sign of the era that we live in and, as a collection of images, will collect a picture of our time.

And suddenly, it all makes sense. These covers don’t say anything interesting or meaningful about our current moment in history, they’re rarely pointed, they’re rarely funny, and they’re rarely surprising. Whatever they’re ostensibly about, they all repeat the same message: “RETWEET IF YOU AGREE.” Turns out they’re a pretty good picture of our time after all.

*Update, Nov. 1, 2017: An earlier version of this piece misstated that the New Yorker ran a cover depicting Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Herbert Hoover on the week of Roosevelt’s inauguration. In fact, the cover was scheduled to run, but was pulled after an assassination attempt against Roosevelt.