One of the textbook examples of negligence revolves around a shop owner who mops the shop floor, leaving it wet, but fails to put up the appropriate “Wet Floor” signage—to act reasonably—to prevent her customers from slipping and coming to harm.

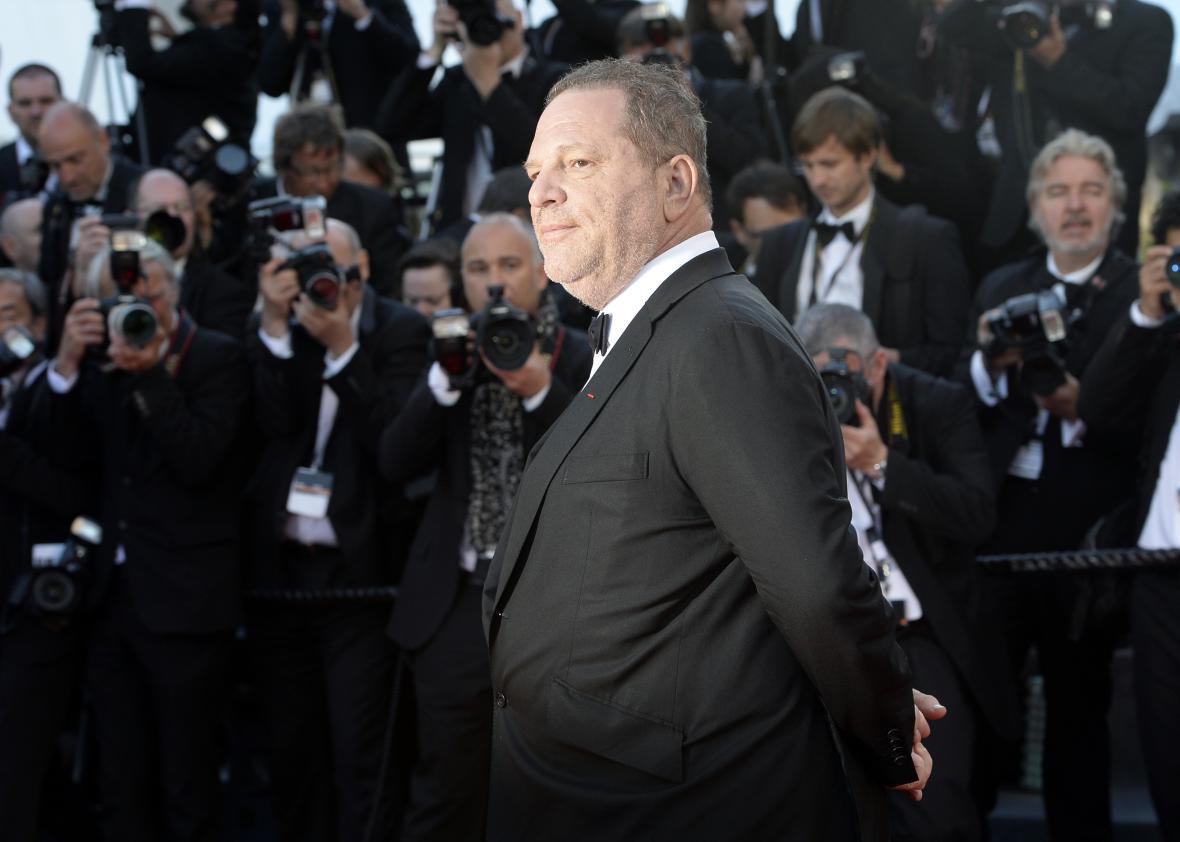

As the list of allegations against Harvey Weinstein continues to grow, it’s becoming clearer that the Hollywood producer was a hazard for women who worked with or went near him, engaging in serial sexual misconduct that his company was reportedly aware of yet did little to curtail, according to a new lawsuit against the Weinstein Company, the first to arise since the stunning New York Times and New Yorker reports earlier this month. (The Weinstein Company board has denied having any prior knowledge of the producer’s allegations, and Weinstein’s reps told Variety, “Any allegations of non-consensual sex are unequivocally denied by Mr. Weinstein.”) Actor and model Dominique Huett, who alleges Weinstein forced oral sex on her in a Beverly Hills hotel room in 2010, is suing the company for negligence over its failure to clean up the floor.

The lawsuit alleges that Weinstein invited the young woman to his hotel room to talk about her career, pressured her into giving him a massage, and suggested he perform oral sex on her. When Huett declined, Weinstein removed her clothing and forced oral sex upon her, and then masturbated in front of her. While the Californian statute of limitations prevents Huett from bringing a sexual harassment claim against Weinstein himself, her lawyer claims the Weinstein Company is still liable because the degree of its carelessness is only now becoming apparent. As more and more women come forward with stories, some breaking nondisclosure agreements, the extent of what the Weinstein Company knew—and failed to act upon—becomes more and more incriminating.

“Defendant failed to institute corrective measures to protect women coming into contact with Weinstein, including Plaintiff, from sexual misconduct despite the Board of Directors possessing actual notice of Weinstein’s sexually inappropriate behavior,” says the suit. “Such acts and omissions demonstrate a conscious disregard of the safety of others. The Board of Directors was aware of the probable dangerous consequences of failing to remove or adequately supervise Weinstein. In failing to do so, Defendant acted with actual malice and with conscious disregard to Plaintiff’s safety.”

Harvey’s brother Bob Weinstein and the board of directors, it claims, knew of “Weinstein’s propensity to engage in sexual misconduct” and of the “substantial likelihood for sexual misconduct” when Weinstein met with an aspiring actress in private. Like a vicious dog or a dangerous inanimate object, they failed in their duty to “control Weinstein in his interactions with women…to prevent foreseeable harm.”

If Huett is successful in her claim, it could open the floodgates for other women who have been harmed by the company’s failure to “remove or adequately supervise” Weinstein. If found negligent for failing to act to prevent Huett’s alleged assault, the number of incidents they may be liable for looks to number in the hundreds.