Actor Robert Guillaume, who died Tuesday at the age of 89, had a long, impressive career both onstage and on screen. In the 1960s and ’70s, he appeared in the Broadway productions of Finian’s Rainbow, Purlie, and a revival of Guys and Dolls, for which he was nominated for a Tony for playing Nathan Detroit. In television, he would make the rounds guest starring on some of the biggest television shows of the era, including Sanford and Son, All in the Family, and The Jeffersons before getting his big break as the wisecracking butler Benson on the sitcom Soap and its spinoff, Benson. While his role as a servant may have been seen by some as a regressive portrayal of blackness in the ’80s (harking back to the stereotypical roles many black actors like Hattie McDaniel were forced to play in Hollywood), Guillaume spoke fondly of his character, which won him two Emmys:

One of the things I was trying to avoid was dignity, that terrible term that you’re either a buffoon if you’re black or you play it with dignity. I hated that idea because I knew that dignity did not make people laugh. I wanted desperately to make people laugh. So I found a way to say what I was going to say in the script without demeaning black people or myself.

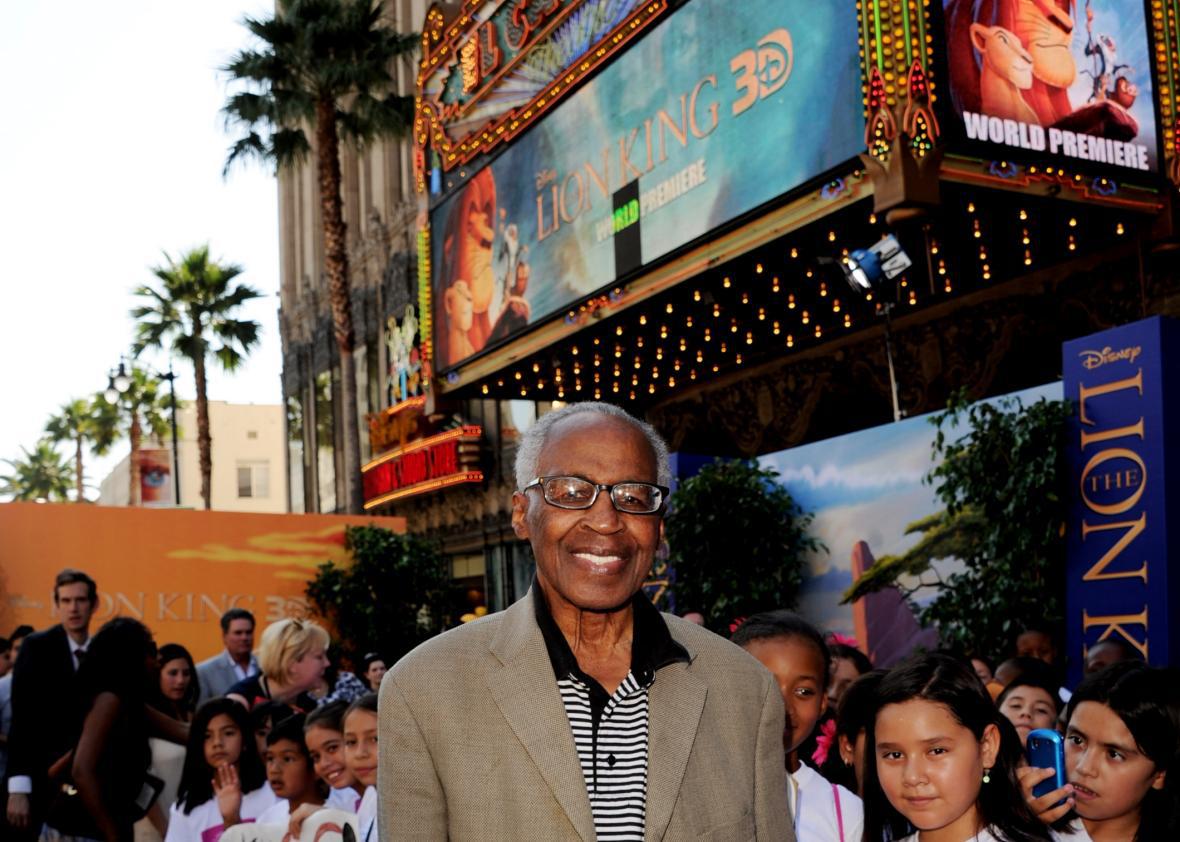

Benson ran for seven seasons and later, Guillaume would find a new audience of fans through his decidedly different role as Isaac Jaffe, editor of a fictional sports news show, on Aaron Sorkin’s beloved, short-lived Sports Night. But to an entirely different generation, Guillaume’s most lasting role is likely his voice performance in Disney’s The Lion King as Rafiki, the odd but wise mandrill who helps Simba discover his destiny as the true leader of Pride Rock. Even if many of the kids who grew up with the film couldn’t name Guillaume, they certainly knew the striking, instantly memorable character he helped create. “I found a liberating element in doing Rafiki,” he said in an interview years later. “The crazier I became, the truer, it became. I could throw caution to the wind, and almost everything we came up with … worked. And I was very lucky, but I had seldom encountered that in some of the other stuff that was not cartoons.”