Battle of the Sexes, Valerie Faris and Jonathan Dayton’s new movie about the 1973 tennis match between Billie Jean King, then a 29-year-old Wimbledon champion, and Bobby Riggs, a 55-year-old hustler long past his prime, is astonishingly effective at capturing the look of the people and places involved in the circuslike spectacle. But appearances aside, is the movie faithful to the real-life history?

For the most part, Battle of the Sexes is remarkably true to the facts, but it does take some artistic liberties when it comes to the order in which they happened.

The Setup

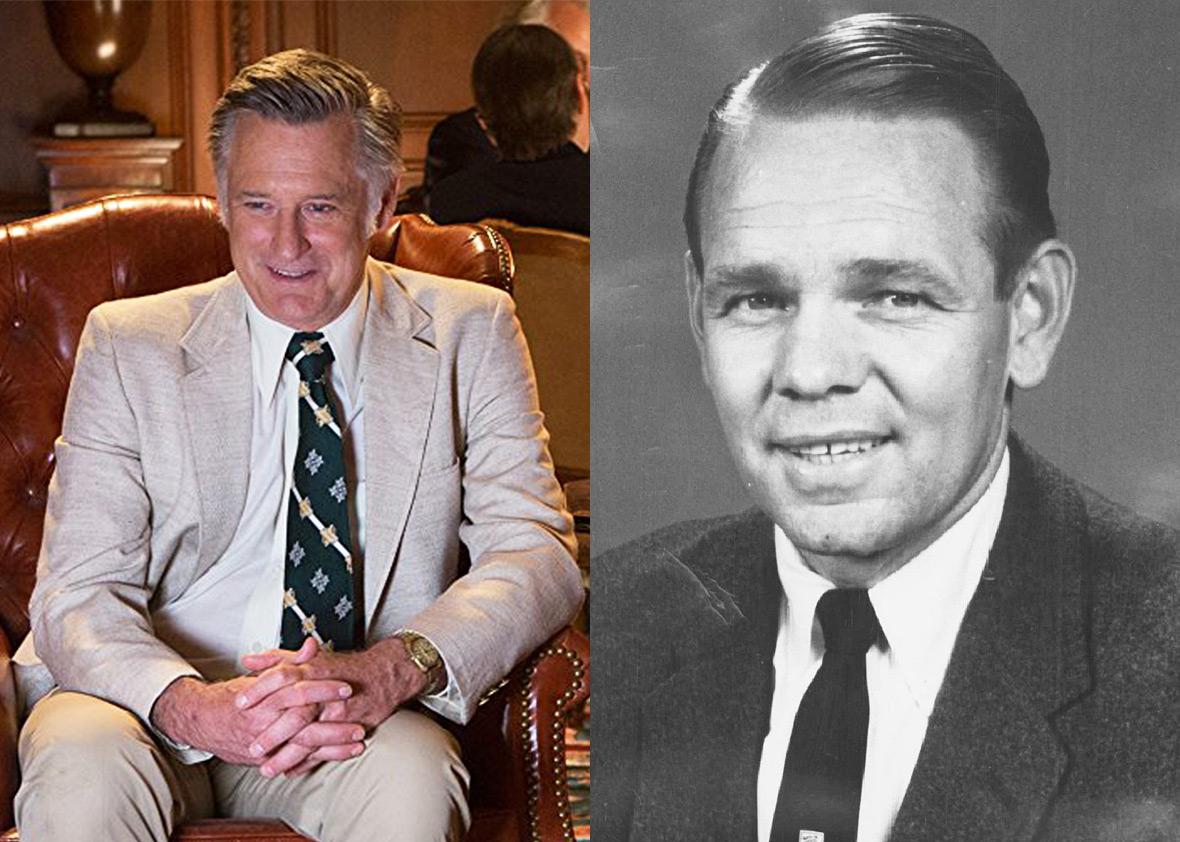

Twentieth Century Fox; The Denver Post via Getty Images

Battle of the Sexes condenses the timeline of the rise of women’s pro tennis to fit more neatly into a two-hour movie, but otherwise its telling is pretty accurate. The showdown between tour promoter Jack Kramer (Bill Pullman) and World Tennis magazine founder Gladys Heldman (Sarah Silverman) really happened much as it does in the movie, albeit in 1970 rather than 1972, as the film suggests. When Kramer refused to increase the women’s purse at his Pacific Southwest Open, Heldman organized a tournament in Houston the same week, and nine players—King, Rosie Casals, Peaches Bartkowicz, Julie Heldman (Gladys’ daughter), Kerry Melville, Kristy Pigeon, Nancy Richey, Judy Tegart-Dalton, and Val Ziegenfuss—signed symbolic $1 contracts to join her tour.

By 1973, although players were earning a pittance by today’s standards, the upstart circuit was successful enough that the U.S. Lawn Tennis Association—which originally stripped the U.S. members of the Original 9 of their rankings and barred them from international team competition—merged its tournaments with the Virginia Slims tour. At that point, players like Chris Evert, Evonne Goolagong, and Margaret Court, who had sided with the tennis establishment, joined King and co. on the road.

Less obvious is why screenwriter Simon Beaufoy has King beating Casals in the 1972 U.S. Open final that opens the film. In fact, that tie-break victory came in 1971, the same year in which King became the first sportswoman to top $100,000 in annual earnings. (King also won the U.S. Open in 1972, beating Kerry Melville in the final.)

Billie Jean King’s Relationship With Marilyn Barnett

Twentieth Century Fox; Getty Images

In the film, King meets Marilyn Barnett (Andrea Riseborough), who becomes her lover, when Barnett is one of the hairdressers coiffing the Original 9 before the big press conference announcing their pro contracts. King and Barnett’s first encounter really did happen in a hair salon, but it occurred in May 1972, a couple of years after the Virginia Slims tour had launched.

Battle of the Sexes shows King torn between fidelity to her husband, Larry, and an almost irresistible attraction to Barnett. In the movie’s version of events, Barnett leaves King before the Riggs match, only to return minutes before the Battle of the Sexes begins. That reconciliation was invented for the movie—in fact, Barnett stuck around and was at King’s side before, during, and after the match. Indeed, according to Selena Roberts’ 2005 book, A Necessary Spectacle: Billie Jean King, Bobby Riggs, and the Tennis Match That Leveled the Game, during the third set, when Riggs required a time out because of hand cramps, “Billie sat with her feet in Marilyn’s lap. … Marilyn rubbed down Billie’s calves to keep the muscles warm while everyone waited to see if Bobby could continue.”

Perhaps because King and her partner Ilana Kloss served as “special consultants” on the film, no mention is made of the acrimonious ending of King and Barnett’s relationship. In 1981, Barnett sued King for what the British tabloids dubbed “galimony,” claiming that she was entitled to a share of King’s assets. Barnett’s lawsuit was unsuccessful, but it outed King, costing her hundreds of thousands of dollars in endorsements.

Bobby Riggs v. Margaret Court

Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation

By all accounts, Riggs was the unrepentant hustler the movie paints him to be. His annoyance at King’s six-figure earnings was partly old-school sexism and partly driven by regrets that his own tennis career had been interrupted by World War II. (He served in the Navy while tournaments were suspended.) Whatever his motivation, he was determined to set up a match against a top female player. When his attempts to lure King failed, he settled for a match against Grand Slam winner Margaret Smith Court on May 13, 1973.

As in the movie, the real Margaret Court tended not to socialize with the other players. The only mother on tour at the time, she traveled with her husband and infant son. Shy, conservative, and religious, she was in many ways King’s polar opposite. Like her movie avatar (played by Jessica McNamee), who decries the “licentiousness, immorality, and sin” of the women’s tour, Court believed that a separate women’s tour encouraged homosexual experimentation. (Now a pastor, Court has actively opposed marriage equality in the run-up to Australia’s Nov. 7 referendum.)

Although the movie shows Riggs offering Court $35,000 to play him in a televised match, the purse was, in fact, $10,000. Riggs’ 6–2, 6–1 drubbing of The Arm in the “Mother’s Day Massacre” is all too accurate, however. And while the movie shows the entire Original 9 disembarking from a plane and immediately scrambling to watch the Court match on coin-operated airport lounge TV sets, A Necessary Spectacle reports that while King, Casals, and Barnett frantically flipped through the airport TV channels while on a layover between Los Angeles and Tokyo, they couldn’t find the game and instead learned the outcome on Casals’ portable radio.

Riggs’ Preparation for the Battle of the Sexes

Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation

The film suggests that Riggs’ preparation for his match against King consisted of endless photo stunts, excessive partying, and a regimen of pills dispensed by an odd man named Rheo Blair (Fred Armisen). According to A Necessary Spectacle, the real-life Blair was “Hollywood’s top nutritional guru … the vitamin czar who had put the bubble back into Lawrence Welk, and spread an extra layer of sheen on the shine of the hardworking Liberace.” In preparation for his contest against Court, Blair put Riggs on a regimen of 415 vitamins a day. (Despite Armisen’s somewhat creepy characterization, there’s no evidence that there was anything particularly sinister about Blair’s views on nutrition or the benefits of protein powder.) Riggs worked hard before the Mother’s Day match, spending as much as six hours a day practicing, but four months later, as the Battle of the Sexes approached, his training was far less rigorous.

Claims That Riggs Threw the Match

Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation

This lack of preparation—and Riggs’ uninspired, error-riddled play during the match—fueled speculation that the old hustler had intentionally thrown the match, perhaps because he had bet against himself, perhaps at the behest of the mob. (The strongest such claim came in a 2013 ESPN story by Don Van Natta Jr.)

Riggs made no effort to hide the extent of his gambling habit (a July 1973 Sports Illustrated profile described Riggs and his best friend Lornie Kuhle betting “on everything from tennis games to memory contests, from the turn of a coin to the flight of a robin”), and according to A Necessary Spectacle, he annoyed both King and his own support team by spending the break after the first set trying to negotiate a change in the odds with his bookie up in the stands.

Still, Riggs always denied throwing the match, claiming instead that he simply underestimated King’s game—and her capacity to ignore his shenanigans.

The Match Itself

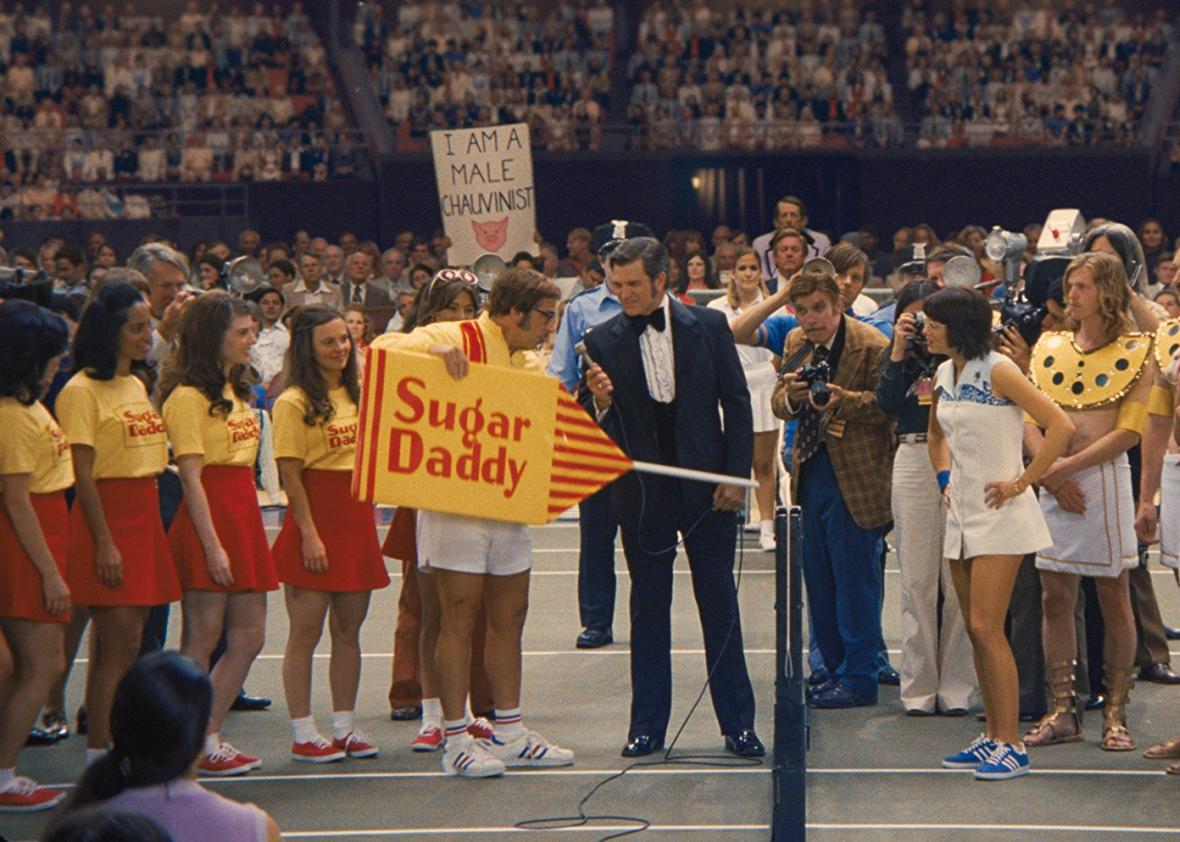

Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation

The Houston Astrodome held 30,472 people on Sept. 20, 1973—still the largest crowd for a tennis match—and the Battle of the Sexes was seen by up to 90 million TV viewers around the world. The movie portrays the spectacle pretty much as it happened. King really did threaten to pull out if Jack Kramer was in the commentary box, so ABC’s Roone Arledge reluctantly fired him. She really did present Riggs with a piglet before the match (though it was brown rather than white). And Riggs really did keep his warmup jacket on for longer than he needed to please sponsor Sugar Daddy.

In 1973, New York Times reporter Grace Lichtenstein followed the women’s pro circuit to write A Long Way, Baby, a dishy chronicle of the season. The climax of the book—for better or for worse—was the Battle of the Sexes. In 2005, Lichtenstein told sportswriter Johnette Howard, “the fact that what was really an inconsequential, made-for-television, silly matchup—an absolute circus—has gone on to attain this mythical status is remarkable, because it shouldn’t have been a landmark of anything.” It was a stunt, a side show, a distraction from real issues in sports and in American society. Nevertheless, it tapped into something so primal that 44 years later the makers of a feature film really didn’t need to change much to make it seem all too relevant to contemporary viewers.

Read more in Slate