There’s been a lot of talk about the unprecedented awfulness of the New York Times opinion page lately: Whether the paper of record was hiring a climate change concern troll, publishing a plea to employ more mercenaries from Blackwater founder Erik Prince, or even checking in with James Kirchick—who argued in 2013 that Chelsea Manning “should be thanking military prosecutors for not seeking capital punishment”—to see how he feels about Manning’s newfound celebrity, nothing the Times has done lately seems to please its critics. Things are bad enough that a Twitter user with the delightful handle of “Ayatollah Cumonme” suspects a Brewster’s Millions type-deal:

But what if the New York Times has always had a habit of publishing horrible opinions in the service of the status quo? What if, in any historical era, the first instinct of every powerful institution is to defend powerful institutions, lest the whole rotten applecart be knocked over? It really makes you think! So in honor of Labor Day weekend, as a salute to terrible editorial page decisions of the past, and most of all, as an exhortation not put too much trust in institutions of any sort, take a look at how the Times handled the Lattimer Massacre.

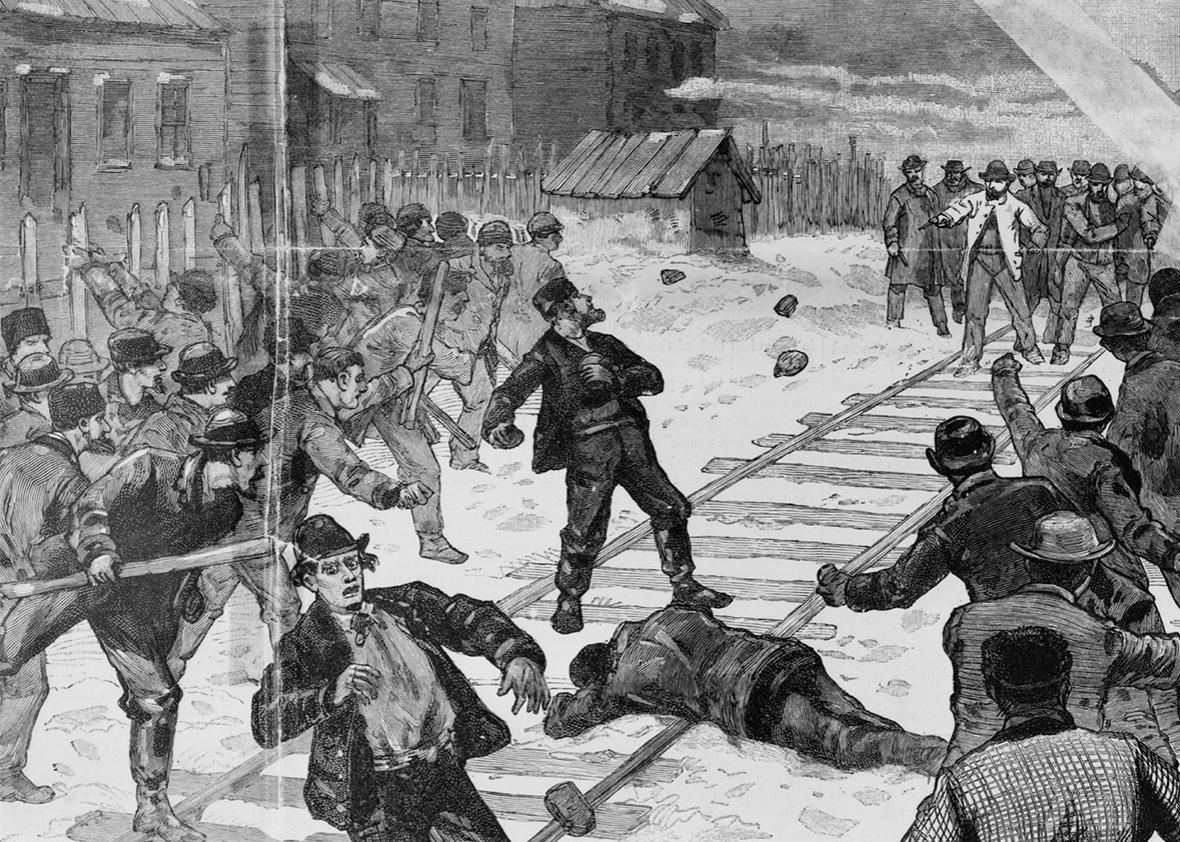

On Sept. 10, 1897, Luzerne County Sheriff James F. Martin and an armed posse of as many as 150 men opened fire on a group of striking Slavic and German mine workers in Lattimer, Pennsylvania, killing 19 and injuring between 17 and 49 more. The strikers were unarmed, and many were shot in the back as they fled. Even in 1897, police had already figured out how to use racism to get away with murder: In a statement to the Washington Post explaining what happened, Sheriff Martin used the word “foreigners” five times—“infuriated foreigners” twice!—and portrayed the unarmed men as bestial and impervious to reason. Here’s his account of what happened—keep in mind that, as the Washington Post noted at the time, “though [Martin] claims to have been brutally assaulted, when seen he did not have a mark on his person”:

I called to the deputies to discharge their firearms into the air over the heads of the strikers, as it might probably frighten them. It was done at once, but it had no effect whatever on the infuriated foreigners, who used me so much the rougher and became fiercer and fiercer, more like wild beasts than human beings. … I fully realized that the foreigners were a desperate lot, and valued life at a very small figure. I also saw that parleying with such a gang of infuriated men was entirely out of the question, as they were too excited to listen to reason. … I hated to give the command to shoot, and was awful sorry I was compelled to do so, but I was there to do my duty, and I did it as best I knew how and as my conscience dictated, as the strikers were violating the laws of the Commonwealth, and flatly refused to obey the proclamation that I read to them. They instead insisted on doing violence and disobeying the laws.

Look what you made me do! Anyway, here’s what the sainted New York Times had to say about Martin’s decision to open fire on civilians, three days after the massacre:

He Did His Duty

An officer of the law is justified in using just so much force as may be necessary to compel obedience to law, and no more. The only question that may be properly asked concerning the shooting of the riotous miners at Lattimore by Sheriff Martin’s deputies is whether any milder measures could have been employed that would effectually have prevented acts of violence. If nothing short of actually killing some of the mob would check its violence, then the killing was justified.

It appears that an excited and angry band of striking miners were about to begin an attack upon a mine in order to compel the men at work in it to join their ranks. The Sheriff and his deputies confronted them. Sheriff Martin read the riot act and ordered them to disperse. The men were too infuriated to heed him. They were mostly Poles and Hungarians. They moved forward upon the Sheriff’s party, resisting his attempts to perform his duty and actually assaulting them.

Here was a plain violation of the law, and what is more important, an unmissable purpose to resist and overcome the officers of the law. The lives of the Sheriff and his deputies were in danger, and the lives and property which they were called on to protect would have been left without protection if they had suffered themselves to be overcome.

The Sheriff had exhausted all peaceable means to control the mob. He must either use firearms or run away. Will it be contended by the sentimentalists who condemn him that he ought to have fled and left the rioters free to execute their lawless will? It was his plain and imperative duty to fire upon the mob. He did fire, and the mob dispersed. It is for such emergencies and for such uses that Sheriffs’ posses and military organizations carry firearms. If it were the law that any mob that refused to obey the Sheriff’s order to disperse should not be further interfered with, guns would not be supplied to deputies.

The killing of so many men is lamentable, but they brought death upon themselves. Their fate will deter other strikers from similar acts of folly and violence. In this country law and public sentiment demand that order shall be preserved and life and property protected. Means are provided for the enforcement of this demand, and neither law nor any public sentiment sets any limit to the employment of these means short of the full accomplishment of their purpose.

To talk of indicting Sheriff Martin for murder is an encouragement to crime and lawlessness.

It’s remarkable how little the argument for police violence—excuse me, law and order—has changed in 120 years. As it happened, Martin was indicted for murder, along with more than 50 of his deputies. They were all acquitted. Crime and lawlessness were, as the Times had warned, encouraged. And people searching for their consciences on the editorial page (or online magazines!), then as now, would do better to look elsewhere. Happy Labor Day weekend!