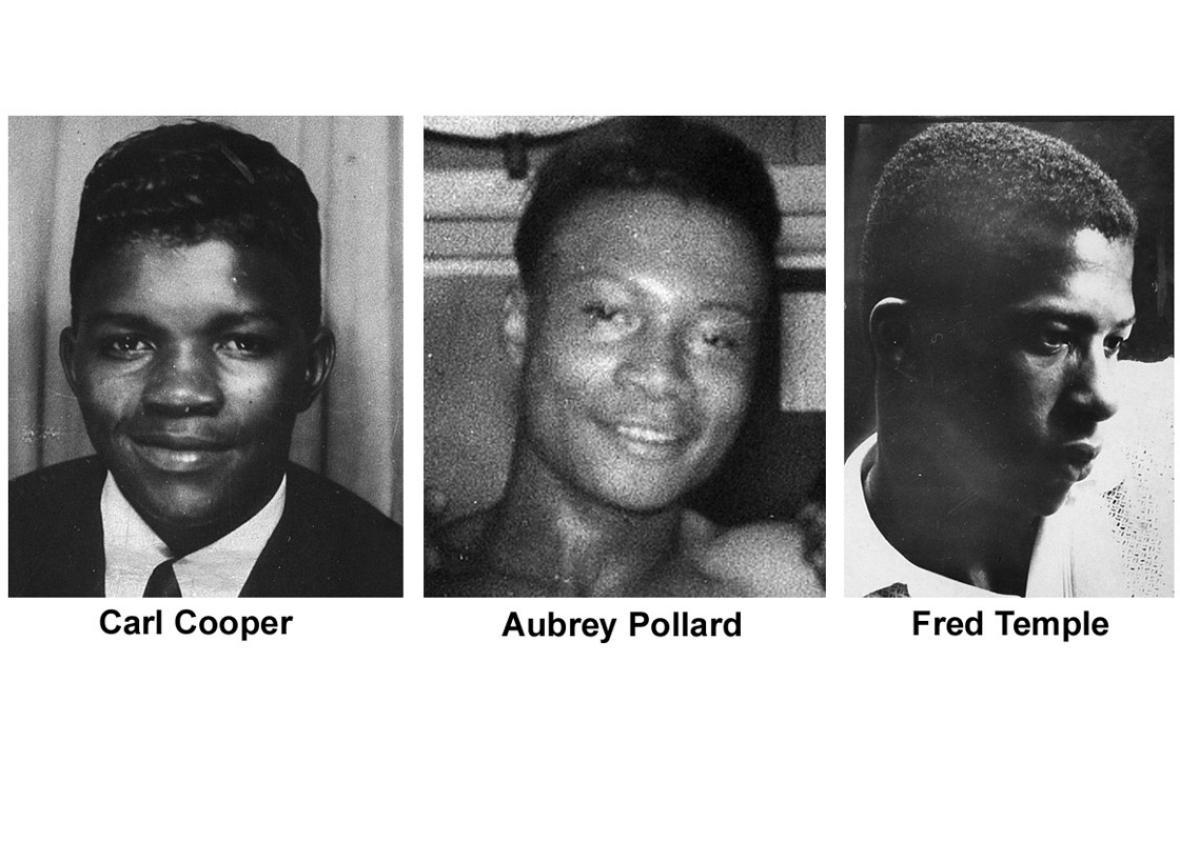

As if to head off the controversy that surrounded their previous collaboration, Zero Dark Thirty, director Kathryn Bigelow and screenwriter Mark Boal include a title card at the end of their latest based-on-a-true story feature, Detroit, noting that the events you have just seen dramatized remain disputed a half century later. For many viewers, the ensemble period piece will be their introduction to the infamous Algiers Motel incident that occurred amid the 1967 Detroit rebellions, in which three black teens—Aubrey Pollard, Carl Cooper, and Fred Temple—were killed by law enforcement in the midst of a raid, and seven other black men, and two young white women, were beaten and tortured according to the victims and several officers present that evening.

Even with that closing disclaimer, however, you still might walk away wondering how much of this harrowing movie is based in truth and how much is creative license. As Boal wrote in Vulture, he took some inspiration from John Hersey’s The Algiers Motel Incident, an expansive if incomplete book that was first published less than a year after the events. (Hersey conducted interviews with almost all the major players involved and their family members, including the white officers who would eventually be suspended from the Detroit Police Department and stand trial over several years.) Boal also referred to contemporaneous newspaper accounts and his own present-day interviews with people like Cleveland Larry Reed, one of the seven men who managed to survive the night, and hired a research team led by investigative reporter David Zeman, formerly of the Detroit Free Press.

While we haven’t hired our own investigative team to fact-check the events of the movie, we’ve consulted Hersey’s book and other reports to break down what’s true-to-life and what’s artistic license.

The origins of the riots

As depicted at the beginning of the film, the unrest began in the wee hours of Sunday, July 23 when the police raided a speakeasy. According to witnesses, the police mistreated the patrons as they arrested them and escorted them out of the building. Three years after the riots, the son of the man running the speakeasy would take responsibility for inciting the unrest in a memoir, though it’s clear that the civilians’ reaction was the result of decades of tension between black citizens and law enforcement.

The earlier police shooting

The scene that follows, in which a young black man is shot in the back and killed after he’s caught looting a storefront during the third day of the riots, is also based in reality. While the names of the main policemen involved have been changed, the character of the police officer Krauss (Will Poulter) appears to have been inspired, at least in part, by officer David Senak, who was 24 years old at the time. On the afternoon of July 24, Senak and two other patrolmen similarly chased after and shot an alleged looter, 34-year-old Joseph Chandler, who died shortly after climbing a fence and escaping. As in the movie, Senak claimed that he didn’t believe that he had killed anyone, and he was similarly (and somewhat bafflingly) placed back on duty not long after, when he was involved in the events at the Algiers Motel. Senak told Hersey in an interview: “We called in the shots to the Homicide Bureau, that we had taken shots at someone but they were uneffective. Later they told us the shots did take effect.”

As reported in an article in the Detroit Free Press a little more than a month after the shooting, Senak was cleared of all wrongdoing in Chandler’s death.

What provoked the raid on the Algiers Motel?

There were purportedly a dozen people total who were subjected to the raid at the Algiers Motel, and Boal leaves out a couple: fellow Dramatics member Roderick Davis and a man in his early 40s named Charles Moore (whose very presence at the Motel that evening was among the many things that were called into question after the fact).

In real life, the details of what prompted the raid are terribly fuzzy. Among the raid victims, there was disagreement as to whether there was ever a gun of any sort in the house: Michael Clark (played by in the movie by Malcolm David Kelley), one of the friends of Carl Cooper (Jason Mitchell), claimed that there wasn’t. (Hersey points out that Clark, whose version of events shifted a lot throughout the aftermath, had spent time in jail for weapons possession and may have had reason to make such claims.) Under oath, Lee Forsythe (Peyton Alex Smith) and James Sortor (Ephraim Sykes) said the same, though Hersey writes that Sortor revealed to him in an interview that Cooper and Clark had been mocking the police, and Cooper had indeed shot off a toy gun. Meanwhile, Juli Hysell (played in the movie by Game of Thrones’ Hannah Murray, and credited on the IMDb as “Julie”) told police that Cooper had “shot a gold and silver blank pistol” in the direction of Forsythe, but “he wasn’t intentionally meaning to shoot him.”

Who killed Cooper?

Detroit’s depiction of the beginning of the raid seems to be another example of Boal making a clear-cut decision in the absence of definitive evidence. In the 50 years since, no one present that evening has admitted to shooting Cooper, who is considered to have been the first one killed, and no one was ever charged in his death. Several officers stated that he was already dead when they entered the house, including Robert Paille (the policeman who seems to have been the inspiration for Ben O’Toole’s Flynn), and Senak said he “believed” that the state police were the ones who entered the house first. The conventional wisdom has been that it’s likely he was struck by bullets as he ran downstairs to escape when police first arrived and began firing at the house from outside.

Detroit, on the other hand, chooses to show Krauss—who is also the ringleader and racist instigator of the entire chain of events—entering the house, shooting Carl, and placing a switchblade next to him in order to frame him. According to Hersey, one state trooper claimed to have seen a knife lying next to Cooper’s body. Hysell, meanwhile, told a Harvard law student working on an article about the incident that she saw an officer place the knife there. (She didn’t, or couldn’t, specify who the officer was.)

The interrogation

Boal and Bigelow appear to capture the general essence of what the young men and women had to endure, according to the survivors and some of the state troopers who were present. They were allegedly subjected to verbal assaults and physical beatings under the pretense that at least one of them had a gun. The women were deemed “nigger lovers.” Robert Greene, the Vietnam veteran played by Anthony Mackie in the film, was accused of being a pimp. As is seen in the movie, state troopers and National Guardsmen who entered the house throughout the night either looked the other way or participated in the abuse in some way, according to some of the victims. One trooper claimed that at one point, Corporal Rosema “came into the room and advised [him], that we were leaving immediately as he didn’t like what he had seen there.” The “death game,” in which the officers singled out some of the teens from the line up and pretended to kill them in another room in order to scare the others into confession, was corroborated by several victims and at least one of the participating officers.

The Detroit News archives, family photos

The other killings

There are a few key elements of Detroit that seem to diverge from historical accounts. The first is the nature of the deaths of 19-year-old Aubrey Pollard (played in the movie by Nathan Davis Jr.) and 18-year-old Fred Temple (played in the movie by Jacob Latimore). In the film, the former is killed when a third police officer named Demens (Jack Reynor) agrees to Krauss’ offer to have a turn to “kill” one of the young men. He brings Aubrey into one of the rooms, and—not knowing that the other officers have been bluffing the entire time—shoots him as he pleads for his life. The moment is played as a twisted, tragic comedy of errors, with Krauss and the others freaking out over Demens’ act.

In truth, it’s never been clear if officer Ronald August, who at first lied about his involvement and then later admitted to shooting Pollard (claiming self-defense, saying he reached for his gun) knew that it was supposed to be a charade. Warrant Officer Thomas (who seems to have been the basis for Warrant Officer Roberts, played by Austin Hébert) initially told police that he saw Senak hand the gun to August and tell him it was a game, but he later said he wasn’t sure if anyone had told him what they were doing.

Fred’s death is, comparatively, less random. At the end of the ordeal, after letting both Greene and Reed run off on the understanding that they will never speak of what has just transpired, Krauss gives the teen the same chance. But Fred can’t deny the injustice, and refuses to ignore Carl’s dead body lying right in front of him. Krauss then shoots him. In real life, Roderick Davis and Reed testified that they last saw Fred, alive, when the remaining men were let go at the same time (the girls were let go separately) and that he had asked for permission to go and retrieve his shoes. Officer Paille would later testify in court that he shot Fred in self-defense.

Melvin Dismukes (John Boyega)

Melvin Dismukes (John Boyega), who at the time was a 26-year-old private guard tasked with guarding a couple of businesses during the unrest, is portrayed, quite sympathetically, as being caught between two worlds. He watches helplessly as the police violence unfolds, but doesn’t do much to curb what’s happening, outside of taking Lee upstairs to try to find the weapon that they were allegedly hiding, so that everyone can make it out of this alive. When he’s brought in for questioning afterward, the police try to get Dismukes to say that he’s the one who killed the boys.

What Dismukes does not do on screen in Detroit is what a couple of victims accused the real-life counterpart of doing: contributing to the brutal beatings himself. In the pretrial examinations for his case a few days later (he was the first of the bunch to be arraigned in court and charged, before August and Paille were even arrested, most likely because he was black), James Sortor testified that Dismukes had beaten him. He was found not guilty of felonious assault.

In a recent interview with Variety about the film, Dismukes said of that night, “I just hoped to calm the situation down that was going on in the lobby. I wanted to help people stay alive, so I did my best to do what I thought would protect them.” (He considers the film “99.5 percent accurate” as to the nature of what happened.)

The aftermath

As Boal has stated, the motel incident was “a night of terror from which Larry never recovered.” As shown in the film, Reed left the Dramatics and turned to church music.

Senak, Paille, and August were suspended from the police force and never put back on duty. The movie condenses several years’ worth of charges and court cases into one case, while highlighting a huge blow to the prosecution’s side when the officers’ confessions to the murders are deemed inadmissible by the judge because they were not read their Miranda rights. (This happened in Paille’s case, which was later dismissed.)

25 years after the incident, a piece in Detroit News featured interviews with the officers and Dismukes. They had largely moved on, living in different cities, while Dismukes at the time was a security supervisor at the stadium that houses the Detroit Pistons. Speaking of the incident and the subsequent fall-out, Senak said, “That whole period is a negative. I’ve spent my life trying to forget about it.” Paille said, “I’ve got nothing to be ashamed of (about) what I did at that place or around that place.” August said, “I’m glad that it’s all behind me. I’ve been married 29 years, and I’ve got five lovely daughters.” Dismukes, meanwhile, said, “I had nothing to do with what they had done. And to this day I still say the only reason my name was linked with them was to get them off. It would put less pressure on them if they could tie a black person in with it. Now you can’t make it a racial issue.”