This article originally appeared in Vulture.

In a show as jam-packed with memorable moments as The Simpsons, it’s hard to say with any certainty where any one bit ranks. What I do know is when you mention anything about Planet of the Apes to a fan of the show, their mind will instantly jump to the words “Dr. Zauis, Dr. Zauis.” Others will happily sing the whole dang score for you. The memory of the show’s fictional Planet of the Apes musical has lasted the 21 years since it aired as part of the episode “A Fish Called Selma” in season seven.

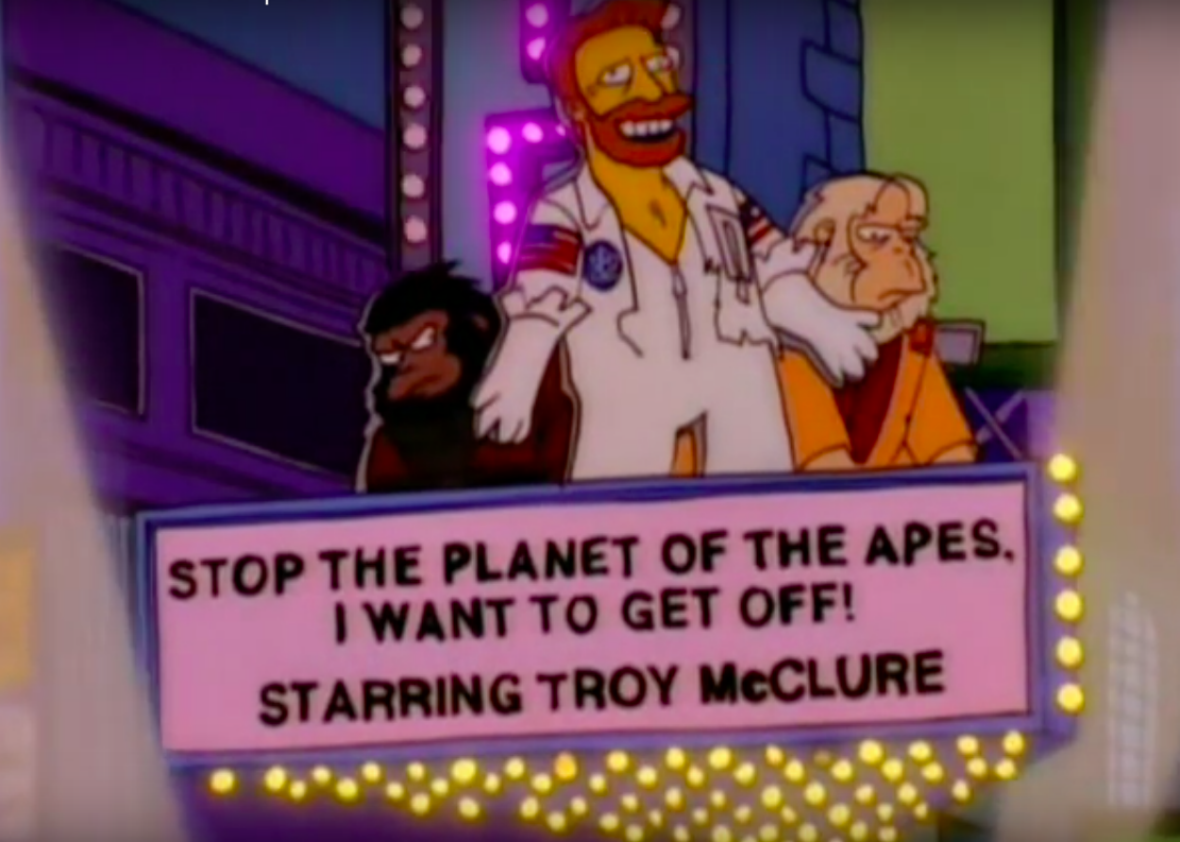

The musical, officially titled Stop the Planet of the Apes. I Want to Get Off!, similarly made a mark on those who created it, if only because how relatively easy it came together. “Usually, we sit around and think for hours and hours until our brains are smoking,” longtime Simpons writer David X. Cohen told Variety about the show’s famously laborious writing process in 1998. “But once every few months, like the time we wrote the musical version of The Planet of the Apes, we really had a blast. I cried with laughter.” The bit has so many disparate parts—’80s Austrian-pop parody, old-school-musical homage, Planet of the Apes, break-dancing, old vaudeville-style jokes—but in the hands of The Simpsons and its writers, it works. Or as Bill Oakley, one of the two showrunners at the time, told Vulture, “[It] was just a magic visit from the joke fairy.”

With the third installment of the rebooted Planet of the Apes series coming out this weekend, here is the story of how the musical came together, from chimpan-A to chimpan-Z.

I. Dawn of the Planet of the Apes

Alf Clausen (composer for The Simpsons, 1990–present): I first came to L.A. in the late ’60s. I was looking for work as a composer and orchestrator, arranger, etc., and I ended up becoming a music copyist over at the Fox music department. Lo and behold, as I’m doing my copying job over there, they give me the Jerry Goldsmith score of Planet of the Apes. I was a music copyist on the original film of Planet of the Apes!

Bill Oakley (writer-producer for The Simpsons, 1992–1998; co-showrunner for seasons 7 and 8): When I was a tiny little kid, it was thrilling. There weren’t many sci-fi movies to begin with, and nerd culture didn’t exist. This was before Star Wars. When you were 6 or 7, this is what you liked before Star Wars, because it was the only thing like that. It was a cool franchise with astronauts and rockets and they went to different planets, and you could get the action figures. That kind of stuff didn’t have a lot of mainstream appeal back then.

Also, almost every person in America has heard of Planet of the Apes and had an idea of what the ending was, or what the gist of it was, like Star Wars. And at that time, before the Tim Burton remake and the prequels, it had this camp-classic status. All the lines like, “Take your stinking paws off me, you damn dirty ape!” occupied a rare place in pop culture.

David X. Cohen (writer-producer for The Simpsons, 1993–1999): I loved it, of course. Who doesn’t? I even read the book—well, the English version. [The movie was based on a French novel by Pierre Boulle.]

Josh Weinstein (writer/producer for The Simpsons, 1992–1998; co-showrunner for seasons 7 and 8): I’ll tell you something—I didn’t see Planet of the Apes until like five years ago. I knew I only knew the whole thing from the parody in Mad Magazine! But when we wrote it, I hadn’t seen it! I didn’t know it! I just knew the ending.

Oakley: The person running the room had never seen it, yet was able to concoct a beloved parody of it just through pop-culture osmosis.

II. Script for the Planet of the Apes

Oakley: Our goal when we took over was to copy season three. Season three of The Simpsons—which we didn’t work on by the way—was the best season of any TV show of all time. When we took over, we said, “What was it about season three that made it so good?” We reverse-engineered it and said, “Well, a lot of the stories were pretty grounded, but they took a couple of crazy leaps out into space with like, ‘Homer at the Bat.’” They did seven Homer episodes, three Lisa episodes, a Sideshow Bob, an Itchy and Scratchy, so we did exactly the same thing. Now as far as the Selma episode, there was an episode in season three where she’s going to marry Sideshow Bob.

Weinstein: Everybody loved Phil Hartman. He was one of those people who, even if he had a straight line in the episode, he’d make it funny. He was funny and super, super kind and charming. We always wanted to do more with him. And by season seven, we felt we could start exploring the secondary and tertiary characters and learn a lot more about them. So we said, “This is our Troy McClure episode.” He’d never actually met the Simpsons at that point.

Oakley: Previously, he’d only been seen on TV and video.

Weinstein: That’s why we gave him the chemosphere house, which is based on a real house. Like, “Oh, it’ll be that Hollywood section of Springfield.”

Oakley: That conversation probably started eight or nine months before we started the script.

Weinstein: There’s a rule that you give two episodes every season to outside freelancers. Jack Barth [the credited writer for “A Fish Called Selma”] is an excellent writer and he’s one of our friends, but it’s tricky. You have to get them up to speed and there’s always a day where you walk them through everything going on on the show at that point. But then it’s like he’s a regular writer and you pitch out the story together. Then they write the draft.

Oakley: The musical wasn’t even in the first draft!

Weinstein: We needed Troy to have a big comeback. That was the big question: What is his big comeback gonna be?

Oakley: It was probably something like a movie or a TV show in the first draft.

Weinstein: I believe [supervising producer] Steve Tompkins had the original concept of Planet of the Apes as a musical.

Oakley: I was out of the room and I came back and the whole thing had been written. I can recall a rare sense of electricity. I wasn’t gone for more than a few hours! I was in editing on another episode and when I came back, this whole thing had been concocted and there was a whole room filled with breathless writers going, “You gotta hear this! You gotta hear this!” People don’t usually do that. Because there are so many great little tidbits that everyone was quoting, I recall being bombarded with enthusiastic pitches that were all hilarious. I didn’t have to approve anything. It was already in the script, thanks to Josh. I was like, “This is great, and I should be out of the room far more often.”

Weinstein: We used to joke all the time about the song “Rock Me, Amadeus.” That was a running joke in the early ’90s among me, Bill, and our friend Paul Sims who did NewsRadio. Between the three of us, we constantly say things like, “Thank you, Amadeus.” After we came up with the idea of a Planet of the Apes musical, I said randomly, “Thank you, Dr. Zaius.” Maybe somebody else may have said it, so I don’t want to claim full credit for it, but somebody said it like the “Rock Me, Amadeus” song, and then it clicked in and people started pitching lyrics.

Cohen: The Dr. Zaius part is probably my favorite. Falco, apes, doctor jokes … There’s a lot going on and it all fits together semi-perfectly, sort of. I’m just remembering how I giddily enjoyed the Dr. Zaius part when we were writing it.

Weinstein: I know David Cohen had one of the best Simpsons lines ever, which is “I hate every ape I see from chimpan-A to chimpan-Z.”

Cohen: No doubt I was going through the different types of apes in my mind trying to think of a funny rhyming lyric. Probably I gave up on “orangutan” and moved on. I certainly did not pitch it thinking it was a high point in the development of human or ape culture. My recollection is I thought it was pretty good and had a decent chance of going in the script, but wasn’t a sure thing.

Weinstein: I guess this happens in lots of rooms, but in The Simpsons room there’ll be 20 minutes or half an hour with everyone silent, thinking of a funny sign gag or a Groundskeeper Willie line, but when someone pitches a great idea or a joke, the feeling spreads. It’s like, when someone pitches a joke like “chimpan-A to chimpan-Z,” you start thinking of even better jokes and it all builds on itself. One nugget of an idea leads to a brilliant sequence, and that’s what The Simpsons room does best, with everybody feeding and playing off of each other.

Cohen: The reason I remember the moment at all is that it got a big reaction in the room from the other writers, much better than I had expected. So into the script in went. To overanalyze it a little, the question is what, if anything, makes the line better than a run-of-the-mill pun on the word “chimpanzee.” The fun of it I think is that you get the joke prematurely during the contrived setup, without even needing to get to the pun part. It’s a slightly weird line in that sense.

Oakley: I don’t think I ever understood what was funny about ending with [“I love you, Dr. Zaius”], but everyone else loved it. And we wanted Troy to have the last line.

Weinstein: I’m not well-versed in musicals, but say, something with a love story like Oklahoma!, you’d expect the ending to be, “I love you, Laurie!” but it’s Planet of the Apes! So that’s partially the joke. But I think it was also just funny.

Oakley: The title, Stop the World, I Want to Get Off was a play or musical, but not a tremendously popular one.

Weinstein: I don’t remember who came up with [the title Stop the Planet of the Apes. I Want to Get Off!], but it came after. We liked the titles of those ’60s movies and musicals. And it just sounded like a good musical name.

Oakley: The script always changes after the table read , and I know there were tons of changes and cuts to this episode because Selma and Troy are both such slow talkers, but in this case, I think the musical was done verbatim from what was in the room that day.

Weinstein: I don’t think there was any part of the song we cut out. I vaguely recall one little vaudeville back and forth that I think we cut. [Otherwise] what you see on the air is what was done in that room in a couple of hours that day.

Oakley: It’s one of those rare bursts of creative brilliance. A lot of the things that people remember and love on The Simpsons were horrible late-night grinds, whereas this was just a magic visit from the joke fairy.

III. Music for the Planet of the Apes

Clausen: The first time I saw the line “chimpan-A to chimpan-Z,” I couldn’t stop laughing.

Chris Ledesma (music editor for The Simpsons, 1989–present): You ask any songwriter or songwriting team in all of songwriting, “Which comes first? Music or lyrics?” and everyone works differently. In our case, it works one way only: The lyrics are written into the script. Then they present it to Alf and they say, “Here are the lyrics for this song, we have this idea.” And sometimes they even have an idea of what the music should be like. Some are very specific, like, “We’re doing a parody of X,” so the music has to be like X. Other times, they’ll give a note like, “in this style.” “Dr. Zaius” obviously had a clear direction because it was “Rock Me, Amadeus.”

Clausen: What I try to do is to get the original source material to listen to, and once I have that, I dissect it. I try to do is figure out what’s unusual about that particular song. Once I get my adrenaline pumping, I have to figure out something that’s actually my own. You may not think it’s my own, but it is my own. It’s different from the standpoint of orchestrations, rhythms, all those kinds of things that make the song recognizable in the eyes of the fans. They think they’re listening to you-know-what, but they’re not.

Ledesma: We’ve never had any rights issues. Though in the last five to seven years, Fox has treaded lightly [after the court decision in the “Blurred Lines” case]. But still, when we do a parody we either walk up to the edge but not jump over or we’ll get the rights to the melody and they’ll write parody lyrics, so we’re totally clear.

“Chimpan-A to Chimpan-Z” [had to be made from scratch]. It was probably in the script as “This is a parody of ‘Rock Me, Amadeus,’ and we need a classic, rousing, showstopping Broadway closer,” so Alf did what he does best.

Alf comes from a showbiz orchestra background. When Matt [Groening] calls him “our secret weapon,” it’s because if you go back and listen to the CDs, you’ll hear how many styles of music he does. Reggae, rock, jazz, didgeridoo for goodness sakes! However, one of his great bailiwicks is big-band and show orchestra—jazz and stage orchestra—which fits right into the Broadway mold. When they gave him the directive to just do a big Broadway finisher, Alf can write this stuff standing on his head, sleeping, and it comes out great.

Clausen: I hearken back to something that was said to me a long time ago by a trumpet player who worked in the studios. He said to me, “You can’t vaudeville vaudeville.” The reason for that particular directive is that he said if you wanted to make something funny, you don’t use funny music to go there. You use music that is extremely serious.

Ledesma: It’s not a part of what a music editor does on other shows, but because Alf is so busy writing the music for next week’s show, I took the job of directing our cast and guest stars. I teach them the songs, I vocal coach them, record them, and edit them into the show. I was not involved when they did “The Monorail Song,”because that was when Jeff Martin took care of stuff, so this was the first I worked with Phil Hartman. He was wonderful. He was not a professional trained singer, but boy, what a performer. Game for anything. Takes direction well.

Working with him is similar to working with so many of the guest stars I’ve worked with who are not trained singers. They’re a little nervous, a little reticent, and you need to coax them to get them out of their shell. The thing I learned early on was that the more I could talk to them from an acting POV, the more I could talk to them about character, and those shades rather than pitch, the better. Also, it was harder to correct the pitch then, so we’d have to do more takes. Now, if it’s only at 90 percent of the pitch but the performance is great, I’ll take it because I can fix the pitch in a second.

For Phil, it was about focusing on the show within the show. He’s not Troy anymore, he’s Troy playing Charlton Heston in this musical, so there’s all these layers of it. The proof is in the performance. He just nailed it, take after take, just getting the shading and the nuance—whatever nuance of this character. The nuance was, “Bigger! Louder!” But to still get the song down and get it right, was a great experience. It’s there forever.

Weinstein: As I said, I hadn’t seen the movie, but when I finally saw it I was like, “Wow, that was a good Dr. Zaius!”

Ledesma: I can’t sing Hank Azaria’s praises enough when it comes to his ability to pull off a song. He’ll be the first to tell you that he’s not a trained singer. As a matter of fact, at the Hollywood Bowl, when we did our big concert in 2014, he got up onstage as the emcee of the thing and the first thing he said to the audience was, “As Hank Azaria, I am nervous and uncomfortable singing, but as all these characters, let’s go!” It’s the same thing. When he was singing this part of Dr. Zaius, he came up with the voice, and once he can get into character and get behind the voice, he will work as hard as it takes to get the tune right.

Weinstein: The ape singers and the woman who goes, “Ooh, help me Dr. Zaius!” were professional singers.

Oakley: And I love that one guy, the other talking ape who’s has the solo “Dr. Zaius! Dr. Zaius!” He’s one of Alf’s regular guys who constantly makes me laugh.

Ledesma: The background singers doing the echoes are from our group of guys we’ve used repeatedly, even up to last Friday. I can’t say with certainty who was on that session 20 years ago, but it would not surprise me if two or three of the guys then were also in the booth with us last Friday.

IV. Animation of the Planet of the Apes

Mark Kirkland (director for The Simpsons, 1990–present): Generally, Simpsons scripts are very detailed, and they really had that one figured out. We just had to do a nice job drawing it and staging it. What we would’ve done in that era would’ve been to watch the actual movie to refresh our memories, and look at the Statue of Liberty.

The script didn’t receive a lot of rewrites. Everything came through in the first draft that I got. It was a script that made me laugh a lot to begin with. The thing that struck me was the satire of those classic movies being made into Andrew Lloyd Webber musicals, like The Phantom of the Opera and Sunset Boulevard. I caught both of those in the theater so I knew what we were trying to do based on those.

My favorite lines were the one is when Bart says, “This play has everything!” and Homer goes, “Oh, I love legitimate the-a-ter!” The saying we talk about in art and drawing, but it comes from food preparation: A good salad doesn’t have everything in it, and here they are enjoying it because it does. They don’t know how bad it is! It’s a critical success.

Weinstein: And then it has break-dancing chimps! It’s one of those things that has ten crazy elements but it all comes together beautifully.

Kirkland: We do have an assistant director Pete Gomez, and I found out that he was a break-dancer, but we also had a lot of visual references. It’s before the era of YouTube that we know today, but we would have had cassettes.

And a lot of key frames were drawn here in the United States, so that there was no room for error when we sent it overseas for finishing. Probably every other drawing for the break-dancing was done here. It wasn’t, “Let me do one or two and then put a bunch of arrows in here to tell the Koreans to make 16 drawings in between these two.” Every other drawing would’ve been done by us, and solidly drawn so that there would be no mistaking. I gave it to Mike with that intention: Let’s do this once, get it right, and make sure we know what we’re sending, because none of this was going to make any sense to anyone in Korea!

Weinstein: I remember going over designs more than usual because we wanted it to be a good musical, but also wanted it to be kind of cheesy. I remember giving notes about the fireworks and background sets.

Oakley: It’s also a rare thing in The Simpsons universe that is fairly well-done. The people who put on that musical were fairly competent. With the exception of the moment when the Statue of Liberty rises, everything else about it is pretty good! It’s not like the average Springfield production of something that’s total garbage. It’s a fairly competent musical with a crazy idea, so god bless the people who put it on.

Kirkland: It was important from our acting POV that the characters on stage were serious. Dr. Zaius was like the real Dr. Zaius and very serious. We let the ridiculousness of the story, the situation, happen and then we played it straight because if we’d been cross-eyed or made funny faces, we would’ve stepped on the joke. There are times where Troy McClure, especially, turns to the audience as though they’re doing their best, but it’s got just atrocious concepts that nobody seems to notice. There’s a humor in that often, in our present-day entertainment, which looks sophisticated or timely when we see it, but when we see it a few years later, we go, “Oh my god, we were entertained by that?” It’s the emperor having no clothes, a little bit.

Weinstein: Part of it is that when people in The Simpsons commit to something, it’s more enjoyable than seeing it half-assed, unless it’s a kid’s school production.

Kirkland: Also, it’s the anchor of the story. The character arc at the beginning is that he’s a washed-up, has-been actor who’s accidentally seen with Selma, who he has no interest in, but his agent tells him it’s good for his career. He’s a hungry, desperate actor who’ll do anything for his career, so he goes along with the romance, and even a fake marriage. Tragically, Selma doesn’t know he doesn’t love her. And then this play happens, and it’s his comeback moment that puts him on the map.

Oakley: Clearly it’s good enough to get Troy the acclaim he needs to get his movie career back on track.

Kirkland: I studied at Cal Arts under the director Alexander “Sandy” Mackendrick, who did Sweet Smell of Success. He’d warn students: Don’t try comedy or satire until you’ve mastered your craft. You have to be as good, legitimately, in order to make fun of it. So when I’d have a sequence like that, it would have been very controlled. I would’ve seen that section and thought, “This is make or break, because if this sequence falls apart, we’re in trouble.” I always take musical numbers reallyseriously, and that begins with the storyboard artist, sitting down and figuring out the best camera angles and the way to tell these jokes without interrupting the flow of the music. If someone had drawn Bart slouching, it wouldn’t have served the joke that he’s attentive and enjoying it. I would’ve had to make sure Bart was sitting straight up in his chair and Homer was wide awake. I was on my game. I don’t remember many retakes. I don’t remember very many, if any, rewrites. I think it came out the way it was originally written, and I think on our end, animation-wise, they did a good job.

V. Return to the Planet of the Apes

Clausen: I certainly remember watching it. That’s one of the reasons I do what I do here and have such a great time doing it. It’s so much fun. You’re not even thinking about the pressure at that point: It’s gone temporarily. It’s a fabulous way to make a living, I’ll tell ya.

Oakley: The reaction that we got for virtually everything on The Simpsons back in those days was that we broadcast it into a void. There was no Twitter. There was alt.tv.simpsons but I’d stopped reading it before then because they hated everything and it was driving me out of my mind. Critics maybe reviewed the show only once a year, so we had no way of knowing what would land unless one of our friends saw it and said, “Hey, that’s funny.”

Dana Gould (comedian; writer-producer on The Simpsons, 2001–2008):I had wanted to do “Planet of the Apes: The Musical” as a sketch on The Ben Stiller Show, if only as an excuse to wear the makeup. The Ben Stiller Show never got around to it, but when I later saw it on The Simpsons and heard the line, “I hate every chimp I see / from chimpan-A to chimpan-Z,” I thought, Yeah, probably better that they did it.

Weinstein: Back then, we were writing because were allowed to write for ourselves and what made our friends in the room laugh! We were writing because we liked it, but now we’re meeting adults who were kids back then who grew up with The Simpsons, so what Mad Magazine did for us, we got to influence people’s senses of humor. It’s only in the last ten, or even eight years, with the internet and all this, that we’re meeting people who grew up with this stuff and can quote our lines back to us!

Ledesma: Let’s put it this way: Alf published a songbook ten years ago—a piano reduction booklet of about 20, 25 songs that would obviously represent the great collection of the best songs in the show’s history. Right in the middle of that book are both “Dr. Zaius” and “Chimpan-A to Chimpan-Z.” They’re right alongside “Checking In” and “See My Vest” and “We Put the Spring in Springfield.” They’re all in there.

Fans talk so lovingly about “the golden era” from seasons one to eight, this falls right in there, and I think it’s also part of the golden era of the show’s music as well. This is not to say that the show’s music has declined in any way, but the show is different. The approach to songs in the show is slightly different. We have 90 seconds more of commercials in the show today than we did 20 years ago. Think about it: a two-minute song, which by song standards is very short, but a two-minute song in The Simpsons today would represent nearly 10 percent of the entire air time. You’re not going to get a two-minute song like you did back then.

Weinstein: On a personal note, it’s one of my favorite things ever, because it’s The Simpsons firing on all pistons. It’s everything the show wants to be, just like Troy McClure says about Jub-Jub: He’s everywhere you want him to be. This musical is everything the show should be and wants to be, and that’s why I think it’s great.

It also was a perfect showcase of Phil. Even though Troy McClure’s a big weirdo, he has sweet underpinnings as well, so it’s a nice legacy for the character. And he loved doing that part. We only talked about this in vague terms, but he wanted to do a live-action Troy McClure movie.

Oakley: I don’t think he had any other episodes where he was the star. Usually Troy and Lionel Hutz were relegated to a line or two here and there. I believe this was the biggest Phil Hartman tour de force we had on the show.

Ledesma: To bring it all the way forward now to last year, when we did our VR couch gag, which was an extended parody of Planet of the Apes. It takes place on the famous beach where the Statue of Liberty is buried in the sand, but if you turn and look all the way to the right, down the beach, also buried in the sand was the relic of the theater where Stop the Planet of the Apes. I Want to Get Off! took place, and there’s a cardboard cutout of Troy McClure half-buried in the sand. When you look at it, not only do you see that, but the music of “Chimpan-A to Chimpan-Z” plays in the background! Look all the way to the right and you’ll have a nice little Troy McClure moment, all these years later.

See also: 6 Pictures of Caesar From the Planet of the Apes Movies With a Caesar Haircut