In its first 10 minutes, the eighth episode of the Twin Peaks revival had already established itself as one of the strangest and most disturbing things ever to air on American television. After Agent Dale Cooper’s evil doppelganger was shot dead by his sometime partner in crime, his body was swarmed by a host of soot-black, semi-translucent figures who seemed to be consuming his corpse, which then sprang back to life after disgorging a slimy sac containing the face of Bob, the series’ embodiment of evil. Then, David Lynch set off a bomb.

The abrupt, and unprecedented, shift from the more-or-less present day to 1945 was disorienting enough, but Lynch was only getting warmed up. To paraphrase another groundbreaking work, we hadn’t seen nothin’ yet. The black-and-white panorama of the New Mexico desert along with a July 16 timestamp gave a hint as to what was coming, but it’s one thing to witness the historic detonation of the first nuclear bomb from a distance and another entirely to push on inside the mushroom cloud, where all pretense of narrative filmmaking fell quickly away. Clouds of boiling smoke gave way to a hailstorm of white scratches on a black backdrop, then to what looked like a celestial birth canal. An eyeless female figure—identified in the credits as “Experiment,” and apparently the same as the one that carved out the insides of an unlucky couple’s heads in the series’ first episode—belched forth a pseudopod containing that same ominous Bob-bubble and also a small, misshapen egg. In an observatory atop a rock spire in the midst of a raging sea, a light flashed, and the Giant (or, as he’s known in this iteration of the show, “???????”) watched humanity enter the nuclear age with a look of mute horror on his face. He floated up to the ceiling as a cloud of golden particles began to emerge from his mouth. Those particles eventually coalesced into a luminescent ball with the face of Laura Palmer, which the Giant’s workmate, Señorita Dido, dispatched toward Earth, beginning its long journey toward a small logging town in Washington.

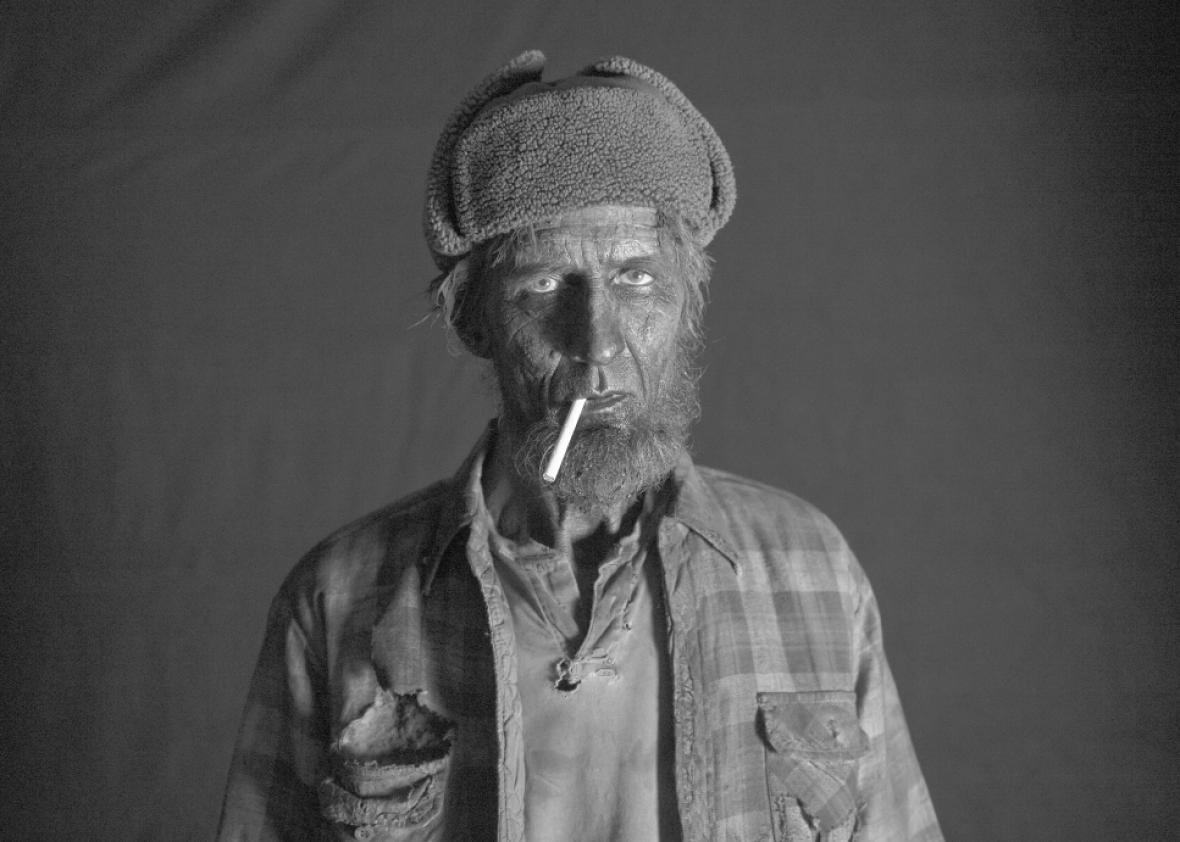

Meanwhile, in 1956, the Experiment’s egg began to hatch in the New Mexico desert, revealing a pulsating, insectile creature within. As a young woman and a young man—whom the credits call Girl and Boy—share a furtive first kiss, soot-men swarm the roads, and one asks a terrified motorist, “Got a light?,” in a voice that crackles with electrical distortion. The Woodsman, as the credits call him, makes his way to a radio station, where he crushes two people’s skulls with his bare hands and commandeers the airwaves to deliver a repeated message: “This is the water, and this is the well. Drink full, and descend. The horse is the white of the eye but black within.” Several people hear the broadcast and drop to the ground, but the Girl merely slumbers and opens her mouth as the insect crawls down her throat. The Woodsman heads off into the darkness as we hear a horse’s whinny.

The details are fuzzy, or unimportant, but in broad terms it’s possible to offer at least a tentative explanation for what’s happening here. The detonation of the atomic bomb, an instrument of mass death and potential human extinction, brings Bob into the world. (The dissonant soundtrack for the bomb test is Krzysztof Penderecki’s “Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima.”) The egg is a product of his birth, as are the soot-men, who come into being around a deserted gas station/convenience store that looks like the mock dwellings built to test the bomb’s effect on human habitations. The Giant sees this happening and creates Laura Palmer as the embodiment of good to balance the scales, just as the good Cooper and the bad Cooper offset each other’s existences. Eleven years later—these things take time—the egg hatches and the insect finds a human host to gestate in. We know from the original Twin Peaks that Leland Palmer first met Bob when he was a child, so 1956 is about right as far as the timing goes for his emergence into the corporeal world. Why the golden bubble of good took another 20 or so years to arrive, and how the embodiments of both good and evil ended up living under the same roof, is something the rest of Twin Peaks might explain or might not.

The idea that Bob was birthed by the atom bomb is so tidy as to be almost prosaic: It’s almost hard to fathom Twin Peaks embracing as tired a TV trope as the origin story. But the way Lynch delivered that information was without precedent, at least as far as the history of series television is concerned. If you’re moderately cognizant with the history of experimental film, you could spot the influences of Stan Brakhage, Bruce Conner, and Jordan Belson, and if you’re familiar with the rest of Lynch’s filmography, you can trace a line backward from Inland Empire’s narrative destruction to Eraserhead’s squishy expressionism and the short films he made in the 1960s and ’70s. (The influence of Lynch’s Peaks co-creator, series TV veteran Mark Frost, is too often discounted, but with this particular episode, it seems fair to ascribe most of the artistic impetus to Lynch alone.) But there’s never been anything like it on television, let alone in the context of a much-hyped miniseries on a major cable network. David Lynch didn’t just detonate a nuke. He blew up the landscape of TV as we know it.

Before the new Twin Peaks began, Slate’s Forrest Wickman reckoned with how it might fit in the TV landscape its first incarnation helped transform. We now have our answer. Just as he did in 1990, David Lynch is giving the television medium a firm, loving shove in the direction of capital-A art, but this time he’s starting much farther down the track. Where Peaks’ incarnation was tailored for the era of prime-time soaps, its second arrives in the era of Peak TV, when cultural sophisticates enthuse over showrunners the way they used to discuss filmmakers or novelists. But for all TV’s advantages in terms of breadth and diversity, the industrial conditions of its production make it virtually impossible for a director to exert the kind of individual control he or she has on a feature film. Lynch had to publicly announce that he was quitting the Twin Peaks revival to get Showtime to give it to him, but he ended up with the artistic equivalent of a blank check, and he’s making no bones about spending it.

The freedom of Twin Peaks also means the freedom to overindulge; it’s possible to love most of what it’s doing and still champ at its self-consciously lugubrious pace or at Lynch and Frost’s monotonous predilection for shrill, nagging housewives. But the series is also demonstrating that for all the strides TV has made, there are still vast continents left to explore. Although Lynch is only 71, it’s possible Twin Peaks may be his final work; he’s said he’ll never make another movie—it’s been more than 10 years since his last one—and it’s hard to imagine the circumstances under which a network would give him the same amount of leeway. But he’s already changed television twice over, and this Twin Peaks season isn’t even halfway done.