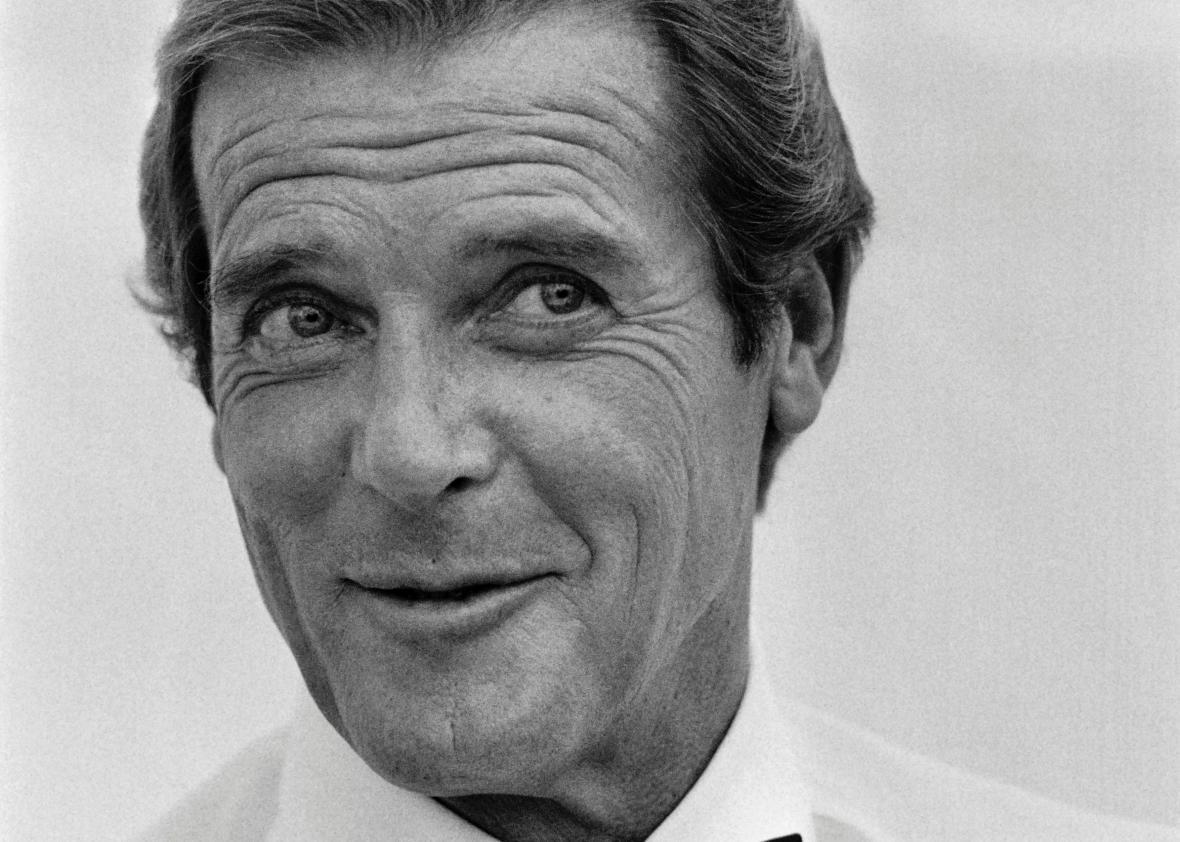

Sir Roger Moore, who played James Bond for a dozen years in the 1970s and ’80s and proved that the series could thrive without Sean Connery, died Tuesday at the age of 89.

Born in London, Moore became famous thanks largely to his small-screen work. He starred as Sir Wilfred of Ivanhoe in the ’50s, appeared as a cousin of the eponymous brothers on Maverick, and much later had a brief run with Tony Curtis in The Persuaders! But it was on The Saint that he really made his name. That show, which was later turned into a Val Kilmer movie, took advantage of Moore’s looks, charm, and perennially raised eyebrow. It’s unwatchably dated today, but its tales of Simon Templar, the rogue who helps people out of jams while avoiding the law, was apparently just what mid-’60s audiences craved.

Moore was still in that role when Connery declined to play Bond in the sixth film of the series, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), which thus starred George Lazenby. Although a later favorite of (some) 007 aficionados, the movie didn’t do as well as hoped, and Connery returned for Diamonds Are Forever (1971), a smash. After Connery again stepped aside, claiming he would “never” return, the producers of the franchise turned to Moore, already 45—Connery had started out in his early 30s—but who they had long envisioned would make an ideal 007.

Moore’s first Bond film, Live and Let Die (1973), is a dreary effort. But since we now view the Bond series as a permanent fixture, it’s worth recalling how shaky it might have seemed at the time. It wasn’t obvious that audiences would ever accept anyone but Connery in the role—some people still haven’t, I suppose—and there was no guarantee the 007 series would become the five-plus decade, nearly-25-film behemoth that it is today. For this reason, Moore is probably as responsible as anyone other than Connery and producer Albert R. Broccoli for the success of the franchise.

The common criticism of Moore’s approach to Bond is that he made the series sillier and less serious—which is thought to be what audiences were looking for in the dismal 1970s. The first part of this isn’t really fair. The series was changing, it’s true: The gadgets got bigger, the jokes got broader, and the action frequently moved to the United States, because of the size of the American market. (This last aspect proved temporary, thank God.) But all of these things are true of Diamonds Are Forever, in which Connery himself adopted a lighter take on Bond. If the series was going in that direction, it wasn’t Moore’s fault.

Still, he certainly enjoyed the more humorous approach to the character. He never viewed it with the same seriousness as Timothy Dalton or Daniel Craig, both of whom treated 007 as a real person. (That can be a problem if you don’t have a good script and competent directing.) He tended to make light of his own acting abilities—over decades of interviews, self-deprecation is the one constant—and he sometimes expressed anguish over the violence in the movies, which was mild even by the standards of the day. Moore’s approach—to interviews and to acting—is perhaps best captured in a revealing remark to the Telegraph: “My James Bond wasn’t any different to my Saint, or my Persuaders or anything else I’ve done. I’ve just made everything that I play look like me and sound like me.” This is certainly simplified, but it isn’t entirely wrong.

After The Man With the Golden Gun, in 1974, Moore and the producers took two-and-a-half years off before turning to The Spy Who Loved Me, still considered his best Bond film by most fans and the one that ensured his stamp on the character would last. Alternately witty and exciting, the film was a giant hit. (Moore called it his own favorite for its combination of “locations and humor,” which gives a hint of how he viewed a successful Bond film.) He was 50 by the time the movie came out but looks fantastic and youthful throughout; the film displays the combination of debonair charm and insouciance that were his hallmarks. He became a much bigger star after it was released and began commanding larger paychecks on the subsequent films. (Like almost every other Bond, his non-Bond work during this era was much less successful; even Connery didn’t have many other big hits until he quit the series.)

Moonraker (1979), Moore’s fourth 007 film, has some good moments before it falls victim to an onslaught of gags, but For Your Eyes Only, two years later, is Moore’s most serious Bond movie. An exciting espionage story with a confusing albeit compelling plot, the movie shows Moore investing the character with traits that he was seldom allowed to show, including anger and occasional ruthlessness. By the time of Octopussy in 1983, Moore’s approach was so popular that the film managed to out-gross Never Say Never Again, a “rival” Bond film (by different producers) that marked Connery’s long-awaited return to the character. Still, when he made his last 007 movie, 1985’s A View to a Kill, he was in his late 50s, and it was clearly time to move on. (He looked remarkably good for his age, but he made an implausible action hero, and his female co-stars weren’t getting any older, creating an off-putting discrepancy.)

Moore didn’t do a ton of work after retiring from the series, but he made several films, pursued charitable causes, and wrote some memoiristic accounts of his time as an actor. Moore was married four times, including to the singer Dorothy Squires. He split his time between the U.K. and Monaco and Switzerland, and in his later years seemed to live a rather conventional life of luxury, replete with beach-going and dining with minor European royals.

As someone who grew up obsessed with all things Bond, I made it my mission to one day interview both Moore and Connery. The latter is retired and no longer gives interviews; even before retiring, he was always prickly, especially when asked about the character with whom he will be forever identified. As for Moore, I tracked him down several years ago; we talked over the phone for 25 minutes or so. It might be the only time in my career that my recording of a conversation failed; I attribute it to anxiety about talking with a boyhood hero.

I did my best to think up some questions about Bond he had never been asked and failed miserably. I could tell that he knew the answers to all my questions by heart, and yet he was nothing but patient and generous, recounting with seeming sincerity and energy stories I’d already read or heard. Several times he paused and took note of how lucky he had been: good health, nice kids, interesting women. I mentioned that Connery still seemed bitter about his Bond experience. Moore, who had a long friendship with Connery, didn’t exactly scold him but made clear that he found that attitude strange. Yes, Moore would always be identified with James Bond, and there were annoying paparazzi to deal with, and it could be tiresome always being asked to order a martini. And yet, he went on, how lucky have I been? I got to play the most famous character in film history, make lots of money doing it, and travel around the world in the prime of my life. Who has time to complain? I always thought this was an admirable answer, especially from someone who showed real generosity in his charitable work.

As we were getting off the phone, I dropped the pretense of reportorial objectivity and told him it was an honor to speak with him and confessed to having spent a good deal of my childhood in his presence. He thanked me, said he appreciated it, and noted how good it made him feel to know that others had derived pleasure from his work. Many people have wanted to be James Bond; if your wish comes true, you should be grateful for it.