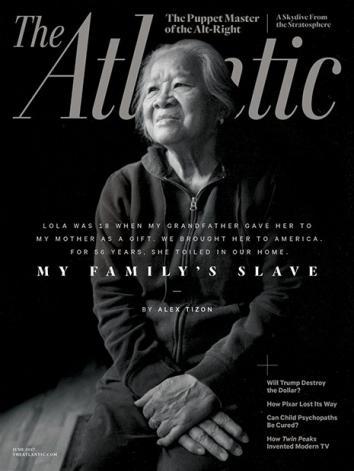

A day before its cover story went live, the Atlantic tweeted, “Coming tomorrow: Lola’s story by Alex Tizon.” The black-and-white image of an old woman, a graceful and elegant Filipina, was on the cover, along with the following text: “Lola was 18 when my grandfather gave her to my mother as a gift. We brought her to America. For 56 years she toiled in our home.” I sensed a storm was coming.

To me, the image of the woman, Lola (also the Tagalog word for grandmother), was familiar. Eudocia Tomas Pulido could have been my grandmother. She could have been my own caregiver when I was small, a yaya assigned to follow me around as I learned to make my way into the world. She could have been any one of the many Filipina grandmothers I have met in my life.

Alex Tizon’s confessional essay is his personal coming-to-terms with the role of his yaya in his life and the way his family used her as a household slave. When Tizon’s father got a job in the U.S., his parents decided to move. “Figuring they would both have to work, my parents needed Lola to care for the kids and the house,” Tizon writes. “My mother informed Lola, and to her great irritation, Lola didn’t immediately acquiesce. Years later Lola told me she was terrified. ‘It was too far,’ she said. ‘Maybe your Mom and Dad won’t let me go home.’ ” Once the family was financially stable they promised they would give her an “allowance” to send back to her family, to help them build a concrete house to replace their dirt-floor hut. But that never happened, and when Pulido’s parents took ill and died, she was not allowed to go see them. Her fears came true. The essay reveals—even if it does not fully grapple with—Tizon’s feelings of guilt and shame for allowing Lola’s position as a “family slave” to continue. The choices he made to appease this guilt are his. This is Alex Tizon’s story.

After the death of his mother, Tizon brings Lola to live with him and his family. He gives her a room of her own. He tells her to relax and do nothing, but he lacks the capacity to understand the trauma she has survived. He fails to ask her what she wants and imposes what he thinks she might want on her. And when she is unable to “relax,” he is irritated. This is his reckoning with what he cannot understand. As much as he says he loves her and is indebted to her, he is unable to let her be. Tizon makes this discovery in the process of writing the essay.

While the idea of holding a woman hostage for 56 years is beyond reprehensible, Tizon was doing that thing I ask my own writing students to do: Go to the scary place. Write about what you don’t understand, what is uncomfortable, risk discovering something about yourself, even if it is unflattering. His widow says he struggled to write this piece for five or six years.

Tizon’s attempt to work through his experience on the page has ignited an international conversation about servitude and modern definitions of “slavery.” For me, it was hard not to read his essay without considering the historical impact of servitude, colonialism, and imperialism. The circumstances surrounding Pulido’s enslavement are part of a far larger narrative.

Tizon’s confessional is sad, horrific, unimaginable. Reading it left me silent and reeling. I saw outraged reactions on social media by non-Filipinos but also posts from fellow writers of Filipino descent expressing the same complicated reaction I was trying to find words for. Though it is clear to us that this form of emotional, psychological, and physical abuse is never acceptable, there is also a connection that many of us feel with this story.

In 1999, I went to the Philippines with five Filipina American charges between the ages of 17 and 22. I brought them with me to help me do research for a book I was working on about the lives of the “comfort women” who were forced into sexual slavery during World War II. One of the first nights we were in Manila, my very excited auntie invited us to dinner in her home in Quezon City.

We sat at my aunt’s dinner table, and the girls were served a full meal—rice and meat stews, slices of fresh mango, whole plates of fish in sweet and sour dressing. There were three kinds of cake for dessert. The katulong—the maid—brought the plates out one by one and offered to serve each of us. The girls looked at each other reluctantly. And when at the end of the meal my students picked up their plates, my aunt insisted they sit. The katulong came back out and began to clear the table.

Later that night we talked about the moment, how it made these American-born Pinay uncomfortable being served like that. “Yes, I know,” I told them. “It feels weird. That’s how it is here.”

The Philippines is a “third-world” nation. The wide disparity between those with and without money makes the culture of servitude a viable option for many born into poverty, especially in the provinces. Sons and daughters, still in school, move away from poor villages to Manila, seeking work as babysitters, cooks, maids, and drivers. Their wages usually get sent back to their families and in return the amos—employers—come to depend on them.

I have seen a professional distance between amos and their katulong and also a kind of familiarity. Pet names like ate, or kuya—Tagalog for older sister or older brother—or in Tizon’s case, lola, for grandmother, are not unusual. Like Tizon, children bond with their caregivers and think of them as part of the family, though they are clearly not. Those ates and kuyas, those lolas, many of whom never make it past elementary or high school, are the very ones who are able to pay for their own siblings, cousins, or children to rise up, attain an education. For some families, this industry of service is the path out of poverty. This too is an extreme, and it may not be the majority’s experience. In the spectrum between Pulido’s suffering and the experience of those who are able to rise out of poverty, there can be many different kinds of relationships between bosses and nannies. In Pulido’s case, she worked, inexcusably, without pay. The abhorrent mentality of treating servants like house slaves is an inheritance of 300 years of Spanish colonization in the Philippines. What we are seeing here is a continuum of servitude.

Another of my aunts lives in a small fishing town in Quezon province. The household work is done by maids who are also mothers and wives. Their children run back and forth between their amo’s house and their own. At night, some of the children sleep with their mothers. On weekends, the women and children might go to their own homes to be with their husbands. And even though there is a certain kind of relaxed familiarity within the household, I noticed my aunt’s bedrooms are always locked at night.

It has been difficult to see wide-sweeping judgment coming from people who have no context nor familiarity with Filipino culture, history, or economics. “My Family’s Slave” cannot be read in isolation. There is a larger issue borne of hundreds of years of colonialism and economic hardship. From the beginning, when I saw that story teased on Twitter, I knew it would be complicated. I do not condone the circumstances of how the Tizon family treated Pulido. But Alex Tizon inherited this story. He had a long struggle to make sense of it before he died at the age of 57. He might have written it in his diaries and kept it to himself, but he did not. He put it out there, and his story, even to the end, is messy. The conversation around Tizon’s essay is important. It will take time, and it may be a struggle to shift cultural attitudes about servitude in the Philippines, but the awareness around Eudocia Tomas Pulido is a start.