This article originally appeared in Vulture.

There is nothing more disruptive to Hollywood than a movie that makes a ton of money while ignoring every current rule about how a movie makes a ton of money. Pull that off, and you may end up with a moment that not only defines the movie year but lays down some new rules for years to come. Four months into 2017, we may already have that film: Over the last two months, Get Out has messed with Hollywood’s head, and with America’s.

Get Out is not the year’s No. 1 movie. That title is currently held by Disney’s live-action remake of Beauty and the Beast, which recently passed the original Star Wars to become one of the ten biggest domestic grossers in history. Beauty and the Beast is huge, but its success is confirmatory rather than subversive. It is an immaculate execution of the studio playbook circa right this minute—an expensive extension and refurbishing of an already profitable and well-known piece of intellectual property (“intellectual property” is what everyone in Hollywood says now when they want something that sounds fancier than “brand”), the formula for which is easily duplicated. It has arrived, and it has been received, and more than a billion dollars worldwide have changed hands, and it will pass through pop culture without leaving so much as the mark of a kiss or a bruise. This is what studios mostly attempt to do now.

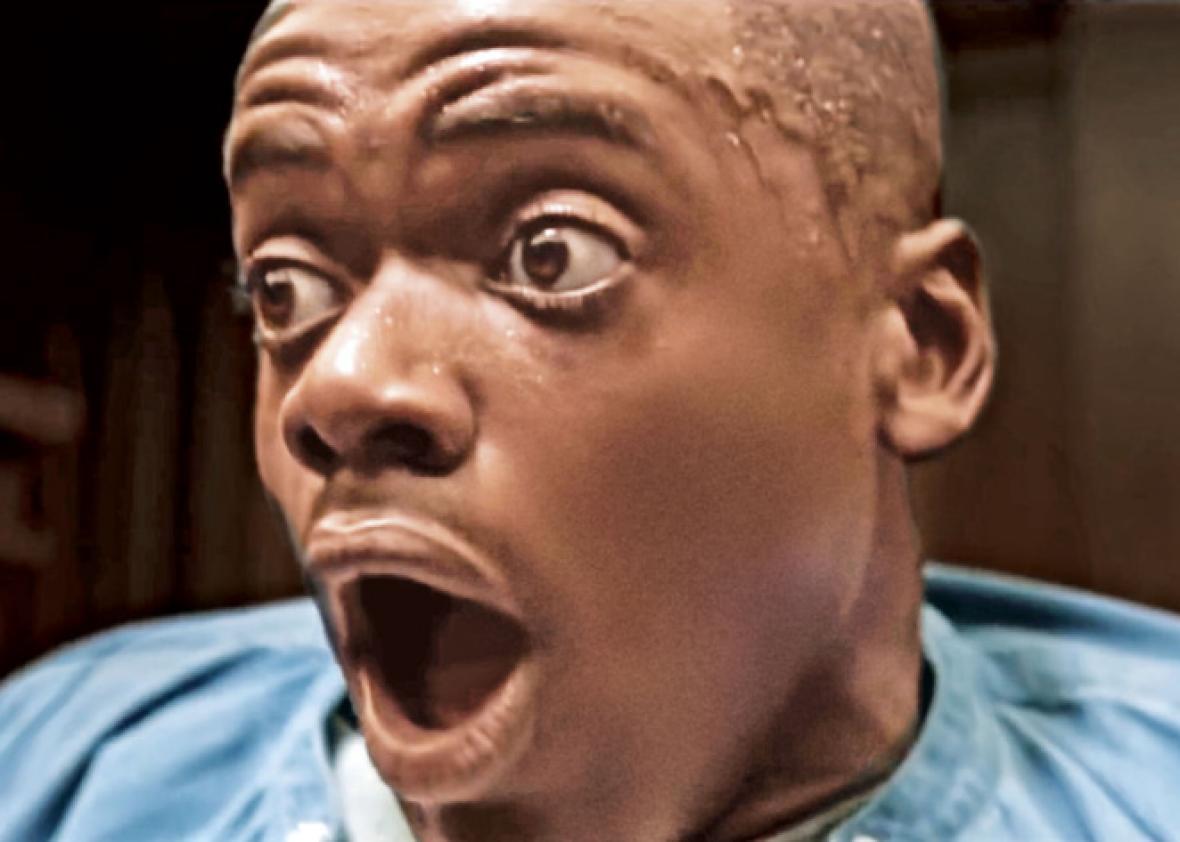

Get Out is different. Everything about it screams “niche,” from the budget ($4.5 million, which is what its studio, Universal, spent to make approximately two-and-a-half minutes of The Fate of the Furious), to the first-time director-writer, Jordan Peele, a cable-TV star whose show ended and who was looking to branch out, to the complete lack of movie stars (although now, Daniel Kaluuya and Allison Williams are nicely on their way), to the genre: horror cut with more than a dash of comedy and of pointed sociopolitical commentary. It is based on nothing; it suggests a formula for nothing; it will not rack up huge grosses in China (or, in fact, any foreign country, most of which are still remarkably inhospitable to movies with African-American casts or themes); it is not duplicable; and it is completely execution-dependent. As a plan, that’s a nightmare. However, one of the defining aspects of Get Out is that it’s not a plan but a movie. And as a movie, its current U.S. gross—$170 million and counting—makes it not only a profit machine but a phenomenon. Get Out’s “multiplier” (jargon for total gross divided by opening weekend) is 5.1; most wide releases hope for 3. A multiplier of 5.1 means a movie is a word-of-mouth smash; a multiplier of 5.1 coupled with the rave reviews that Get Out received means it’s imaginable that the film will reemerge at year’s end as part of the awards conversation, a finish line few probably imagined.

But Get Out has accomplished much more than that: It has written new chapters in a couple of front-burner cultural narratives that were already compelling public attention—one about African-American representation both onscreen and behind the camera, and one about Donald Trump. A month into the Trump presidency, audiences were clearly ready for a piece of pop art that captured the stricken, petrified gallows humor of the moment. Potential headlines, think pieces, and hot takes were baked right into Get Out’s story. If you haven’t seen the film, it’s about a young black guy who spends an unnerving weekend with his white girlfriend’s apparently liberal family, which on one level makes it a deeper, darker 50-years-later version of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner reconceived by the Sidney Poitier character as a nightmare, and on another makes it a Key and Peele sketch that sets up a great premise and, unlike most sketches, has the time, room, and impetus to explore its most unnerving ramifications.

It was an accident, although it now feels like an inevitability, that Get Out arrived in movie theaters the very weekend that Moonlight not only won the Best Picture Academy Award but, thanks to the Oscar telecast’s twist ending, appeared to win only by withstanding a hurricane, gently but determinedly wresting its moment from a stage full of churning, baffled white people. Barry Jenkins’s overwhelmed and elated acceptance—“I’m done with it!”—probably had many meanings, but in one sense, the phrase couldn’t have been more in sync with the tone of Get Out, which, with alternating currents of fear, disgust, clear-sightedness, and amusement, offers a view of the interaction of white and black America that turns “I’m done with it” into a symphony. (One of the sneaky joys of writing about the movie is the case it makes that I, a middle-aged white man writing in effusive praise of it, might be the devil. Take that as you will.)

We have had other African-American-themed movies—most recently Hidden Figures—that outperformed (white) expectations and reminded Hollywood, yet again, that a vast and powerful audience continues to be underestimated and underserved. But Get Out is the first movie that seems in part to be a critique of the whole subject: It suggests that when you encounter a smiling white progressive who talks enthusiastically about the importance of diversity and sticks out a helping hand, you might want to look for the dagger sheathed in the sleeve.

That probably extends to anyone in Hollywood currently saying, “We should make more movies like Get Out!” Easier said than done, and easier still to translate that into “We should get Jordan Peele to direct the next Marvel movie” or similar suggestions. Hollywood is an engulfing beast, and its instinct is to incorporate—to get someone like Peele aboard the ship rather than to re-steer the ship itself. Warner Brothers has reportedly been wooing him to direct a remake of the 1988 anime sci-fi film Akira that has been in development for more than a decade. As counterintuitive as it might seem to look at his wholly original work in Get Out and say, “This guy should be doing remakes,” it is, in a way, all that a studio knows how to offer in 2017. Mid-budget films where a writer-director could once let his own ideas flourish are close to extinct now, so the highest compliment a studio can pay is to hand over a high-value property—a remake, a sequel, a reboot, a franchise—and in doing so, invite a hot new talent to convert from being an underminer of the Plan to a component of it. To pursue an alternative approach—simply asking a filmmaker what he most wants to do next—would be to privilege passion in a way that is completely at odds with the way studios operate. After a success, Hollywood’s message is not “Change us.” It’s “Join us.”

But Get Out itself has plenty to say on the subject of the depersonalization that assimilation can bring about; no spoilers, but it’s built into the plot. (And there are layers of delightful irony in Get Out leading all contenders in a corporate enterprise like the upcoming MTV Movie Awards with six nominations—including the brand-new and echt-2017 “Best Fight Against the System.”) In any case, Peele has plans of his own—in an interview with Business Insider, he discussed Get Out as the first of five thrillers about different “social demons” that he hopes to make over the next decade. “I really want to continue to nurture my own voice,” he said recently.

With Bradley Whitford doing a dead-on incarnation of the guy who hastens to tell you he loved Obama so much he would have voted for him for a third term if he could, some have claimed that the primary target of Get Out’s dark-comedy scorn is woker-than-thou dad liberalism. But Whitford’s character is not what he seems, and Get Out knows who and what the greater enemy is. Right after the election, some people, desperately searching for any silver lining, resorted to “At least some great oppositional art will come out of the Trump era.” Well … with the possible exception of Melissa McCarthy’s first Sean Spicer appearance, we’re not there yet. Art takes time. But we are in the first stage of anti-Trump pop culture: the arrival of movies, theater, and television conceived long before this moment that nonetheless have something to say about it. It’s part of the reason for the attention paid to Lynn Nottage’s Pulitzer Prize–winning Broadway play Sweat, which personalizes the economic despair caused by the decline of manufacturing jobs, and to Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale, an adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s dystopic 1985 novel about an anti-female theocracy, the current resonance of which is lost on no one. And it is very much a part of Get Out, which, with its side-eye aimed at the airy delusion that we’re all part of a “post-racial” society, unquestionably plays differently than it would have during a Hillary Clinton administration. The movie suggests that a black person’s worst fears are not paranoia but foresight. It felt a lot easier to “Yes, but” that notion six months ago.

You hear sometimes that art like Get Out got “lucky,” that its success is a matter of propitious timing and the convergence of fortunate circumstances. Don’t believe it. It’s the job of artists to put their palms to the ground and feel for subsonic rumbles; they write about what’s on their minds with the faith that soon, there will be reason for it to be on the minds of others. So Get Out, which finished shooting more than a year ago and had its first trailer up on YouTube a month before the election, isn’t the movie of the moment so much as the movie that felt the moment coming. It’s a film that says to its audience, “Things are so much worse than you imagine.” And they have been all along. In 2017, that’s the punch line we’ve been asking for, and maybe the punch we deserve.

See also: Jordan Peele’s Get Out Is Terrifying, Socially Conscious Horror