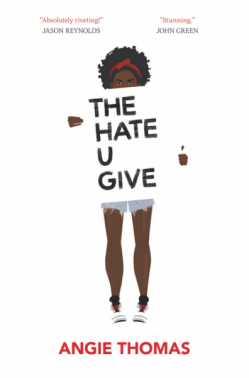

Angie Thomas’ debut young adult novel, The Hate U Give, has been at the top of the YA best-seller lists for six weeks. It’s a poignant story told from the perspective of a 16-year-old black girl who weathers all the adolescent storms that have long been tropes of the YA genre—growing apart from childhood friends, the first-time rush of crushes, the evolving, more complicated relationships with your own parents. Teenagers will undoubtedly relate to modern-day pop cultural shoutouts to the likes of Drake and the Nae Nae. But The Hate U Give is more than just a series of familiar growing pangs. Undergirding Thomas’ narrative is the polarizing issue of police brutality, as her protagonist, Starr, is forced to grow up—fast—after witnessing a police officer kill her childhood friend, Khalil, during a traffic stop. Starr’s story echoes the real-life narratives so often glossed over or all together ignored by the news cycle when it comes to police shootings of people of color.

During George Zimmerman’s 2013 trial for the killing of Trayvon Martin, Rachel Jeantel became a reluctant, unwitting media sensation on the witness stand. As the last person to speak to Martin right before he died (besides his killer, of course), she had to testify about what she heard while speaking to her friend on the phone while he was being attacked. Jeantel was scrutinized almost as much as Martin’s social media footprint and school records, mocked and ridiculed for being big, black, and defensive in the midst of the antagonistic cross-examination by Zimmerman’s lawyers. Some, including other black people, felt she single-handedly ruined the case against Zimmerman because she appeared to have an “attitude.”

Throughout the ordeal, little attention was paid to how Jeantel must have actually felt and the trauma that she went through. (With some notable exceptions here and there.) But then, so often, the innocent bystanders who are forced to witness these violent incidents firsthand are just footnotes in our coverage of police shootings—a cable news sound bite, an anonymous “Witness #__” cited in police reports. The Rachels, Dorian Johnsons, Feidin Santanas—their close proximity to violence and tragedy, and how it must affect their psyches and spirits, is an afterthought, if it’s ever a thought at all.

The Hate U Give deftly unpacks what it might be like to suddenly find oneself in such a draining, nightmarish position, and recenters the plight of the police shooting victim to focus on the victim-adjacent. After Khalil’s death, Starr wrestles with an array of conflicting emotional and environmental forces. She blames herself for losing touch with Khalil, her first crush and kiss, as they grew older. She struggles with going public with her identity and speaking out against the officer who shot him three times in the back—ultimately preferring to remain anonymous for many reasons, not least of which is her fear of being scrutinized by her communities in the predominantly black, impoverished Garden Heights neighborhood and her tony, mostly white classmates at Williamson, 45 minutes away. She’s angry at the way in which the media paints the easygoing, if slightly troubled, Khalil as a gangbanging villain who deserved what he got, while the cop is positioned as a victim who feared for his life in that moment.

Thomas brings us deep inside Starr’s world and into her head, her protagonist guiding us through the contours of her mental state throughout the entire process. The skeleton of the story is instantly recognizable: the fatal encounter with the officer, uncomfortable and accusatory interrogations by the investigating police force. The incident’s evolution from local news story to media circus, the riots, all the way through to the trial and aftermath. Within these beats, however, we get the distinct voice of a teenager, one who must deal not only with ordinary teenage feelings of insecurity and identity crises but the suffocating weight of racism and brutality. “When I was twelve, my parents had two talks with me,” says Starr, the moment we realize that her and Khalil are being pulled over. “One was the usual birds and bees … The other talk was about what to do if a cop stopped me … I hope somebody had the talk with Khalil.”

Her account of what happens next in those moments are full of palpable dread. It vividly conjures how terrifying a routine traffic stop can be for a person of color. Thomas explicitly weaves in a reference to a real-life, infamous death to describe how Starr has trouble breathing in the rush of the aftermath—in fact, there’s no shortage of callbacks to the actual deaths that have helped galvanize the Black Lives Matter movement. Later, Starr reveals her fear of having to become an activist rallying against injustice: “I always said that if I saw it happen to somebody, I would have the loudest voice, making sure the world knew what went down. Now I am that person, and I’m too afraid to speak.”

Starr is a fully realized, transparent character, one who isn’t afraid to share her recurring nightmares about Khalil’s death or the death of their other friend, Natasha, when they were just 10 years old—a casualty of a drive-by. She’s funny and frank while discussing why she feels like she can never be herself around her black friends in Garden Heights or her with her white friends at Williamson. Her relationship with her family, which includes her mother, a nurse, her father, a former gang member turned neighborhood store owner, and her Uncle Carlos, a police officer and colleague of the cop who shot Khalil, is challenged and strengthened by the circumstances—her family helps her navigate the daunting process, even when she wants nothing more to be left alone; even when the expected outcome of the trial comes true and the world around them spins into chaos.

The “Black Lives Matter special episode” has morphed into something of a pop culture genre over the last few years, a chance for writers to address these ripped-from-the-headlines issues in bottled increments on shows from Law & Order: SVU to Black-ish to New Girl to Scandal, usually from the points of view of characters who experience it from a distance. (Shots Fired, a new drama that inverts the typical scenario, with a white person dying at the hands of a black cop, is perhaps the first network show to take on BLM and police brutality as its central conceit.) But there’s something particularly powerful about seeing this story told within the parameters of the YA genre, targeted toward young readers who may be grappling with the issues raised by BLM themselves. The Hate U Give immerses you in the experience of its protagonist, forcing you to remember not only the victim who died but the victim who lived.