The first thing founders Isaac Harris and Max Blanck want you to get right about their business, as they recently explained over phosphate and sodas, is the name: It’s the Triangle Waist Company, not the Triangle Shirtwaist Company. But as other industry-defining titans have since discovered—Federal Express, Kentucky Fried Chicken, Blackwater—if you build an organization that earns worldwide name recognition, quibbling with the public over the little details is a losing battle. And no company has ever been as synonymous with shirtwaists as Harris and Blanck’s scrappy little enterprise, no matter what name is on the official letterhead. On Saturday, the Triangle Shirtwaist Company (sorry, boys!) marked its 106th year in the public eye—more than a century in which Harris and Blanck’s bold and disruptive innovations have served as a blazing torch lighting the way forward for business leaders the world over.

No one remembers it today, but the shirtwaist industry was a staid, conservative affair when Harris and Blanck burst onto the scene with a simple, revolutionary question: “Shouldn’t work be exciting?” That sense of excitement began with the company’s greatest resource: its employees. Lots of employers pay lip service to diversity, but Triangle practiced what it preached, actively recruiting women and recent immigrants from day one, a powerful (if implicit) rebuke of the divisive tactics of the Trump administration. The results speak for themselves: a creative, flexible workforce (70 percent female!) whose diverse perspectives helped nurture the first sparks of innovation into a self-sustaining conflagration of fun and profit.

But a diverse workforce has diverse needs, and so Harris and Blanck had to shake up the compensation system to provide their employees the flexibility they required. While some of the more productive Triangle Shirtwaist Company employees were paid by the week, to accommodate those who appreciate a more traditional employer-employee relationship, those who made fewer shirtwaists were paid piecework rates instead. This system, which spread uncontrollably to other industries, turned out to be a smart way to keep costs down while providing workers with the freedom to be their own bosses. In fact, Harris and Blanck burned down the entire concept of “bosses” and “employees,” preferring to think of Triangle as a family, building team spirit at the company’s beloved “lock-ins” and regular bonfires. No wonder that, even in the face of outside agitation, Triangle preferred a personal, one-on-one management style, as Blanck explained to the New York Times in 1909. “We told the girls that we were willing to listen to any complaints and to receive any suggestions from our employees themselves,” he said, “but we had to draw the line on three or four East Side gentlemen stepping in to tell us how to run our business. It is an outrage the way the girls who have remained loyal—and they are the vast majority of our force—have been treated by these people and their sympathizers.” The facts bear out Blanck’s rosy view: Nearly a third of their employees swear they will never work anywhere else.

Washington Evening Star

One warning to would-be followers of Blanck and Harris, however: Their success is not just a question of tone. Work/life balance, often overlooked by startup founders, is something of a religion at Triangle. Employees who miss the factory’s 8:00 a.m. start time are encouraged to take the rest of the morning off, allowing the for the “me time” that makes for higher—some would say “frantic”—productivity once the doors reopen. Need to stay home due to sickness or family emergency? Triangle’s “sabbatical” program—miss a day, take the rest of your life off—built the kind of loyalty money can’t buy, and laid the groundwork for the kind of employee dedication we routinely celebrate today. Would that heroic Lyft driver have taken one last fare en route to the hospital to give birth without trailblazers like Triangle?

The Triangle story hasn’t been all warm employee relations and scorching hot returns on investment, however. When Triangle moved into a hip, open-plan workplace in the Asch Building, government regulators initially balked at the lack of stairways. The Triangle Shirtwaist story could have ended there, but the company rose from the ashes like a phoenix. Rather than wander the confusing maze of government bureaucracies looking for an exit, destroying their building’s flow of people and ideas with an additional staircase, or, God forbid, breaking up their workday with fire drills, they installed a light, flexible fire escape—perfect for Triangle’s light, flexible business model. It was a searing rebuke to the outdated, innovation-smothering regulatory state, paving the way for modern heroes like Uber, a company that, as Matthew Yglesias wrote for Slate in 2011, “exposes the idiocy of American cities’ cab regulations.” Imagine the consumer-friendly world we could live in if every industry faced that kind of purifying flame!

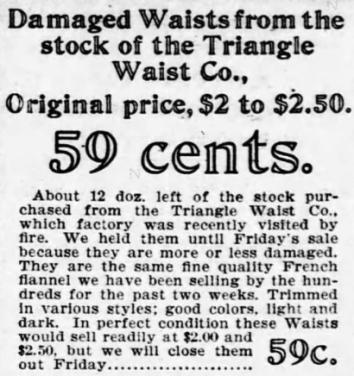

Harris and Blanck, like so many others who followed in their footsteps, saw an opportunity that everyone else missed: By clearing the dead brush of their industry’s cartels and the regulatory state that fed them, they were able to positively incinerate shirtwaist prices. That’s how Triangle became a model for forward-thinking industrialists from West Virginia to Bangladesh. Left-wingers and other enemies of innovation may try to to throw cold water on their approach, but for consumers feeling the heat, affordable, convenient shirtwaists will always have more sizzle. So what’s next for the company that cooked up the gig economy? Harris and Blanck aren’t saying, and neither are their employees. One thing’s for certain, though: At the hottest companies all over the world, the Triangle Shirtwaist Company model is catching fire.