Some people come to Sundance for the movies, some to take meetings, and others just for the chance to spot a celebrity making his or her way over a Park City, Utah, snowdrift. But in the last several years, a new possibility has emerged: going to Sundance to watch TV. Although it wasn’t the first time the festival had shown episode work, the 2013 screening of Jane Campion’s six-part miniseries Top of the Lake seemed to break the dam for good. Every year since, there’s been a steady increase in the amount of episodic work screened during the course of the country’s most prestigious film festival, further blurring the line where television stops and movies begin. (Film and TV critics spent the end of 2016 fighting over who would get to put O.J.: Made in America on their top 10 lists.) This year, there are over a half-dozen events organized around advance screenings of shows like Amazon’s I Love Dick, ABC’s Downward Dog, and Fox’s Shots Fired, as well as the CNN miniseries The History of Comedy and Netflix’s Abstract: The Art of Design.

In past years, most of Sundance’s TV programming has amounted to a carefully curated sneak peek at already-completed shows, but this year, for the first time, the festival opened up its submissions process to episodic work and virtual reality, getting some 500 entries in all. The result was three separate showcases, one dedicated to independent pilots and two to short-form episodic series, with subjects ranging from “the elitist parenting culture of Silicon Beach” to a teenager who discovers she is pregnant with an alien baby. This will also be the fourth year the Sundance Institute has convened an Episodic Story Lab, which admits writers who have never previously sold a pilot to an intensive 10-day program followed with a year of support from Sundance’s staff and the lab’s experienced advisers.

“This is totally a fascination and an interest of ours, and we feel like this is just the beginning,” says Sundance programmer Charlie Reff. “We’re totally in experimentation mode for now, just seeing what it’s capable of.”

TV used to be where independent directors went to pick up a paycheck in between films; scroll through the credits on a season of Six Feet Under, and it’s like a Sundance family reunion. But increasingly, it’s become the place for at least some of those directors to spread their wings, following an audience for idiosyncratic work that is steadily migrating from the big screen to the not-so-small. Four years ago, Jill Soloway attended Sundance as the director of a little-heralded debut feature called Afternoon Delight. This year she’s back as the creator of the boundary-pushing and critically beloved Transparent, with three episodes of a brand-new series under her belt.

Brett Morgen is a Sundance veteran who’s been bringing movies to the festival since 1999, but his latest project is When the Street Lights Go On, the pilot for an as-yet-unproduced series about murders in a small suburban town. Street Lights began life as a feature film script hot off the 2012 Black List, which Morgen, known for documentaries like On the Ropes and Cobain: Montage of Heck, planned to be his fiction debut. “I’d been doing commercials for 17 years,” Morgen says. “I couldn’t think of anything better to do with my own money than to buy a property I really wanted to develop.” But even with a modest projected budget of $7 million and an actress whom Morgen calls “without question the biggest star of her generation” attached as a lead, the movie was dead in the water. “I figured we’d hit the end of the road,” Morgen says. “But then I got a phone call: ‘What do you think about adapting it as a TV show?’ ” And with that, he says, “I’ve basically just walked you through the last seven years of independent cinema.”

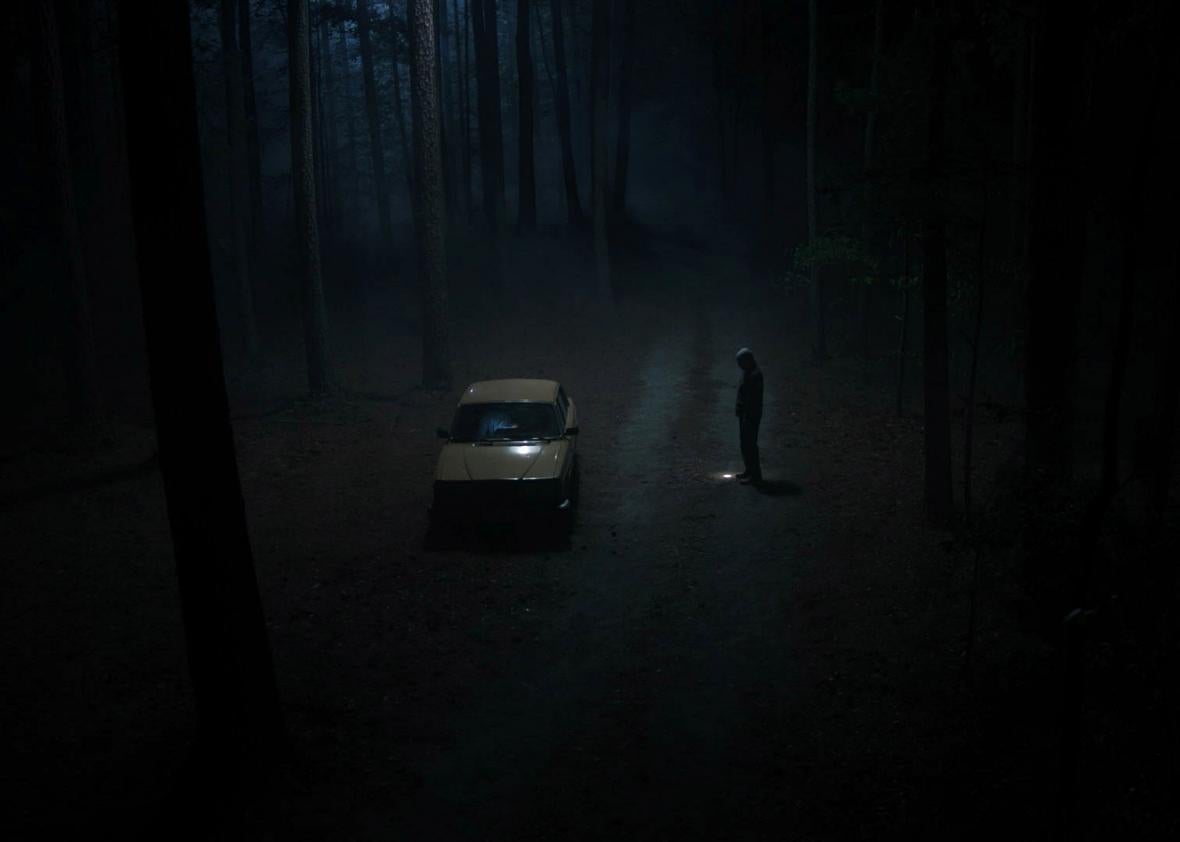

Making Street Lights for Paramount Television was, says Morgen, “as pure as it gets. There was literally no compromise made for anyone or anything.” Although it’s set in the 1980s, there’s no tinge of Stranger Things nostalgia for the era, which Morgen, who is 48, remembers with passionate loathing. During production, Morgen took his young cast members to a Duran Duran concert, and remembers thinking, “I cannot wait to fucking destroy the ’80s.”

Peak TV notwithstanding, Morgen says he hasn’t watched a scripted TV series since The Sopranos, and he drew his crew, including the great cinematographer Ellen Kuras, largely from the world of film. The pace is slow, the lighting, inspired by the photographs of Gregory Crewdson, moody. “There’s a three-minute scene in the middle where the kids exchange two woods of dialogue,” Morgen says proudly. “It’s so anti-TV.”

Apparently, Hulu agreed. Although the streaming provider had been “supportive every step of the way,” by the time it was finished, its programming strategy had shifted, and a gloomy period drama with no major stars in the cast was not something they were interested in proceeding with. (Morgen is still working on “a big comic-book adaptation” for Hulu, which tells a different story about recent trends in independent filmmaking.) Pilots that don’t go to series, like Kanye West’s attempt at a Curb Your Enthusiasm–esque HBO sitcom, are usually condemned to the studio vaults, but after Hulu passed, Morgen got in touch with Trevor Groth, Sundance’s director of programming, and asked if there might be a way to get it Street Lights in front of an audience, no matter how small. For Morgen, the aim was less to get it made into a series than to provide “closure” for himself and the people who worked on it. “I’m just happy to show it,” he says. “I’ve never enjoyed the experience of the festival as a film director. It’s too stressful. This feels totally different.”

That said, Sundance is as famous for its deals as for the films it shows, and that could one day go for its episodic programming as well. After screening two episodes of their animated series, Animals, at Sundance in 2015, Mark and Josh Duplass got an order for a full season from HBO, and though Animals wasn’t renewed, the Duplasses went on to make their next show, Togetherness, for HBO as well. As I was talking with Reff about Pineapple, a stylish short-form series about a mystery in a small town, the news broke that it had been acquired for a new digital platform called Blackpills. The single greatest obstacle to the maturation of the episode form is the lack of financially viable distribution channels outside the major networks and streaming providers. Sundance can’t develop those alternate channels on its own, but at least it’s giving the industry a place to look for the next big thing.