Amazon’s The Man in the High Castle, which returned for its second season on Friday, envisions an alternate 1960s where the Axis won World War II and has divided the world, or at least America, between Germany and Japan. To many observers, this is the only salient fact about the show.

It would be almost impossible to watch The Man in the High Castle, let alone write about it, without considering the results of the presidential election and the ascendancy of American white nationalism. It makes an unfortunate kind of sense that reviews in the New York Times, the Atlantic, and the Guardian all describe the new season of the show with some variation on the phrase “newly relevant.” James Poniewozik puts it bluntly in the Times: “But if it would be hyperbole to treat the series like a documentary, it would be denial to say it plays no differently now than it did before.”

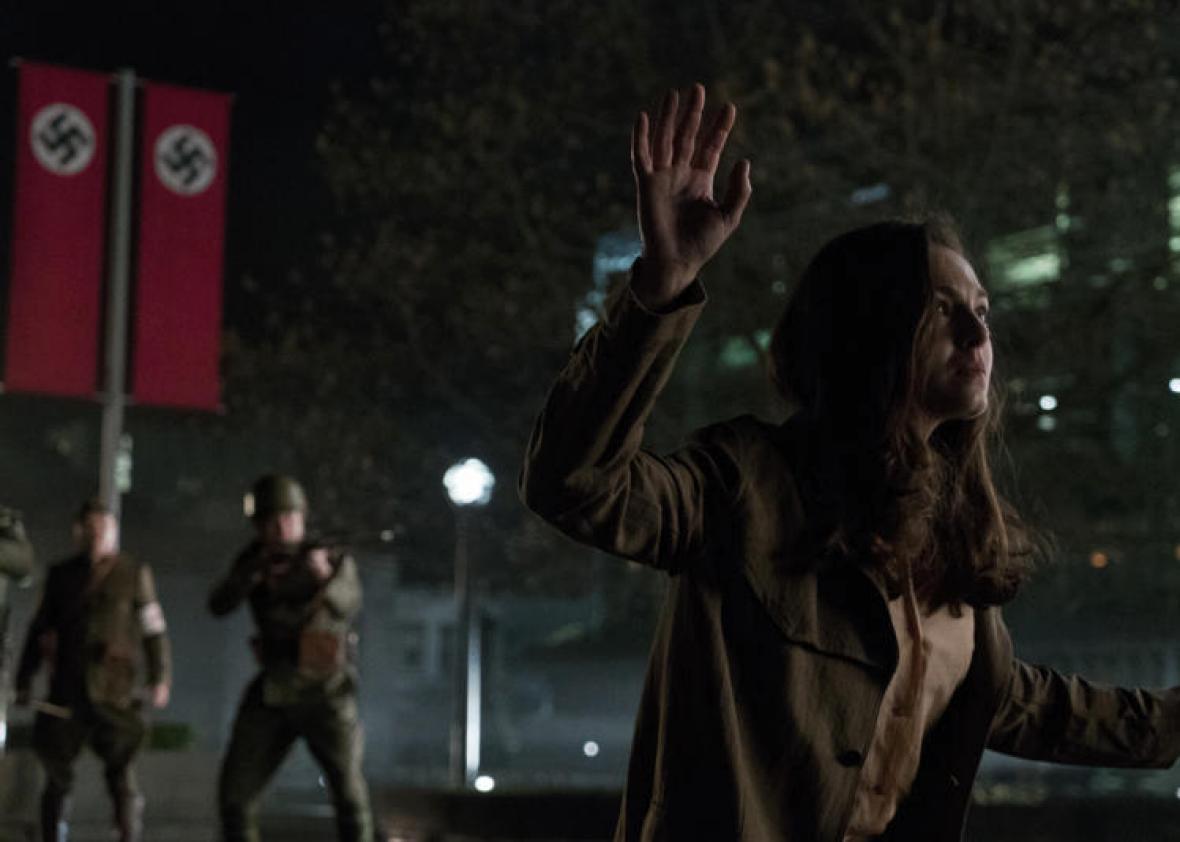

In this contextual vortex, it’s all too easy to flatten The Man in the High Castle, to make it “the show about Nazis running America” and to sardonically fire off a bunch of jokes. But this superficial association flattens the artistic value of the show and the statements it does make about life under fascism.

Though much of The Man in the High Castle takes place in and around Nazi America—and, in the second season, Berlin—its best elements avoid the blunt shock value of seeing swastikas hanging in American high schools. The series occasionally grasps at the surreality and sheer weirdness of Philip K. Dick’s source novel, particularly in Japanese Trade Minister Tagomi’s (Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa) attempt to adjust to life in a hallucinatory alternate timeline in which the Allies won the war—a world that looks much if perhaps not quite entirely like our own. It’s no coincidence that this plot is also one of the show’s most stylish; the show succeeds in large part because of how mesmerizing it can make repetitive, glum conversations about individual helplessness.

On the other hand, much of the dialogue is as clunky as the characters’ attempts at espionage. Many of its attempts at profundity fall deeply inside the lines. Though it happens less than in the first season, the second still relies on the “Nazis? In America?!” conceit for much of its imagery. Some of this effectively indicates the full extent of what’s been lost under the regime, like the fact that black music is only available on pirate radio stations. The more cheesy elements, like a cop show that simply trades the U.S. government for the Reich, are less successful, primarily because they feel more like winks to the audience than organic parts of the show’s world. The more heavy-handed The Man in the High Castle gets, the harder it is to watch, and the harder it is to engage with. Fascism, as we all know, sands down nuance.

Still, the show’s cast of spies, soldiers, and rebels is sufficiently complex to maintain interest. Obergrüppenfuhrer John Smith (an icy Rufus Sewell), an American-born officer in the Reich, struggles with the knowledge that his son, suffering from a congenital degenerative disease, is marked for death under his own regime’s eugenics laws. The anti-fascist resistance frequently makes indefensible decisions, allowing murder and atrocity in the name of disrupting, or simply frightening the regime. All of the protagonists are caught somewhere in between, trying to understand what individual goodness looks like in a world not much more complex and broken than our own.

These complications knot together to form The Man in the High Castle’s far more bitter political lesson: The weight of history and of institutions intellectually and morally overwhelms the individual, no matter what she tells herself. The series’ premise seems to pose the question of what ostensibly good people do under fascism. But then Juliana Crain (Alexa Davalos) finally meets the titular Man in the High Castle (Stephen Root), an intelligence asset to the resistance who has somehow made or discovered film reels showing a vast array of possible timelines. (One such film, The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, is a pivotal object in the first season.) She discovers that his true power lies in an ability to expose contingency: Each of his films depicts a different present or future, with wildly divergent moral positions for each person depending on the timeline. Anyone who might think they’d always be noble in the face of atrocity is likely to have done nothing, or worse, depending on their circumstances.

Even with the many crimes of the Nazi state in mind, The Man in the High Castle reframes history to suggest the U.S. government and its past aren’t so great, either. Nazi high schools give history tests with questions about the number of slaves each Founding Father had and “American exterminations before the Reich.” A German woman euphemistically describes her husband’s work running a state television station as “helping people think”—or not think, as the case may be. (He is later used as a pawn in a resistance operation.) Reading Huckleberry Finn with his father, a young boy in Brooklyn asks a question only a hair more explicit than most of today’s political discourse: “How can he be good if he’s black?”

The second season eventually moves past its early focus on individuals being blown about by the winds of history to focus on a bigger threat—the potential for nuclear war. Without spoiling too much, the season spends a decent amount of time telegraphing a nuclear standoff between Japan and Germany, a sort of Axis version of the Cuban Missile Crisis that still assumes the baseline competence of the persons in power. But it also sees their selfishness and capacity for cruelty as a given and accordingly posits an inexorable march toward total, apocalyptic doom. In the final analysis The Man in the High Castle is, perhaps, a bit too relevant.