It’s been a strange year to be gay in a Hollywood blockbuster—the strangest part being that you can now actually be gay in a Hollywood blockbuster. Well, sort of gay. Big-budget movies in 2016 have taken to assigning sexuality to previously neutered supporting characters, like Sulu in Star Trek and the raving scientist in Independence Day, both of whom in this year’s sequels pointedly embraced husbands we never knew they had. (No kissing allowed, of course.) They’re barely better than the status quo of coded gay characters, like Kate McKinnon’s eccentric ghostbuster or maybe those two women pushing a stroller in Finding Dory, but unambiguously gay characters in movies of this scale really are something new. A tender hug between two married men in a film that will travel around the world is progress, however halting.

Or is it? In Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, a franchise-launching, megabudget Warner Bros. movie, there’s an obvious gay liberation metaphor behind the central plot, and speculation about the sequels has centered on how gay they will be. The hinges of the celluloid closet creak. In Fantastic Beasts, the homoerotic elements mostly manifest in the form of metaphor and heavy suggestion—but the franchise could be poised to take a much bigger risk in future films, as it explores the possibly romantic relationship between the new series’ villain, Grindelwald, and one Albus Dumbledore.

Fantastic Beasts has the many plot threads we’ve come to expect from the overambitious launch of a major Hollywood franchise, but its primary mystery involves the investigations of Percival Graves (Colin Farrell) and his strange relationship with Credence Barebone (Ezra Miller), a teenage boy under the influence of an anti-witch brigade. In one early scene, Graves, an “auror” (a kind of magical detective), lords over a young Credence and whispers to him suggestively, trying to tease out some sort of information. The sequence, dark and backlit in a 1920s New York alleyway, takes on an uneasy sensual air as the two figures lean into each other in a creeping embrace. Barebone, played by Miller with his saucer eyes and bottled-up intensity, seems to have a confused, if not overtly sexual interest in his older suitor; Graves’ motives are less clear, but he doesn’t exactly rebuff the boy’s clear desire for intimacy.

Their shadowy relationship, full of loaded body language and suggestive glances, comes to a conclusion (spoilers) along with another plot thread that borrows from the X-Men school of transparent gay metaphors. Let’s see if I can explain this without getting any emails from Potterheads: Throughout Fantastic Beasts, there’s a dark force destroying buildings and roads across Roaring ’20s New York, and eventually it becomes clear that it’s an “obscurus,” or a dark magical force that forms when a young wizard is forced to repress his magic for fear of violent persecution. So, essentially: If young wizards can’t come out and healthily express their (magical) energy, they develop sinister black clouds around them that ultimately lead them to self-destruction. Wink, nudge—we get it. Barebone, the boy, turns out to have developed the most powerful obscurus the world has ever known, the one that’s been tearing through New York. He’s basically the most repressed wizard ever. Pair this allegory about repression with his breathless affection for the handsome detective, and the subtext just about rises to the level of text.

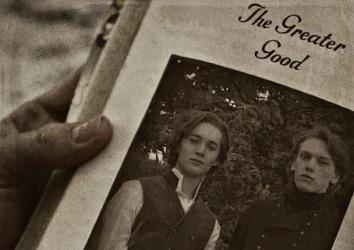

From here, an even bigger spoiler and a bit of Potter lore become important and suggest that these homoerotic themes are no accident. Graves, the boy’s object of wayward affection, turns out to be Grindelwald in disguise. Grindelwald is the Beast franchise’s new big bad—a great dark wizard who a young Dumbledore met after he graduated from Hogwarts in June 1899. Dumbledore and Grindelwald, both among their generation’s most gifted wizards, entered into a deep friendship that included plans for a revolution that would install wizards as the world’s rightful overlords. The young Dumbledore also, it seems, fell in love with Grindelwald.

Screenshot via Warner Bros.

Although the always-enterprising gay blogosphere has already begun to refer Grindelwald as “Dumbledore’s gay lover,” Rowling has hinted that the love was unrequited—if not necessarily unconsummated. Grindelwald seems to have recognized his friend’s affections and exploited them to advance his dark plans, not unlike how he does the same to the powerful, repressed teenage boy in Fantastic Beasts. How, um, far Grindelwald goes with that exploitation isn’t clear, and much remains rumor at this point. (We know from elsewhere in the Potter universe that the men eventually become fearsome enemies and duel in 1945, when the new movie franchise is set to end.) Alas, the end of Fantastic Beasts will not put an end to the speculation about Grindelwald’s sexuality. When the real man is finally revealed, he’s played by a snarling Johnny Depp, his hair dyed platinum and his manner suggesting a deeply alarming cross of David Bowie and Milo Yiannopoulos. We get only a few moments of his giddy Aryan flamboyance, but the performance so far certainly seems … suggestive.

Fantastic Beasts is the first of five planned movies, and the notion that two feuding gay wizard lovers might be the ultimate hero and villain of a Hollywood franchise is a dream, especially in our “enlightened” age of stealth queers and chaste hugs. Even if the characterization of Grindelwald seems to indulge hateful stereotypes about predatory gay men, that might still be preferable to sterilized gestures at this point. At least he’s a real character. But if astute Potter fans are correct and Grindelwald merely twists Dumbledore’s affections, J.K. Rowling may finally get the opportunity to correct course on the character. The author famously declared at a 2007 event that she “always thought of [Dumbledore] as gay,” setting off endless clashes among critics and readers about what that really means. The late ruling on Dumbledore’s sexuality seemed indisputably extra-textual, nowhere to be found conclusively in the books. If the goal was to allow readers to experience a heroic gay character without the label, the coyness felt instead like an author unable or unwilling to go where her “thinking” had actually taken her.

Rowling, who is writing the screenplays for the new movies herself, set off a flurry of headlines when she said future Beasts films would explore Grindelwald and Dumbledore’s relationship in depth—and, perhaps, finally bring Dumbledore’s sexuality out of the shadows. Her opportunity is immense, given her wide creative latitude with this material. Let’s hope she assembles the metaphorical crumbs she’s left all around Fantastic Beasts into something with real power and nerve. She’d liberate her most beloved character—not to mention the Hollywood genre in which she’s chosen to expand her singular world.