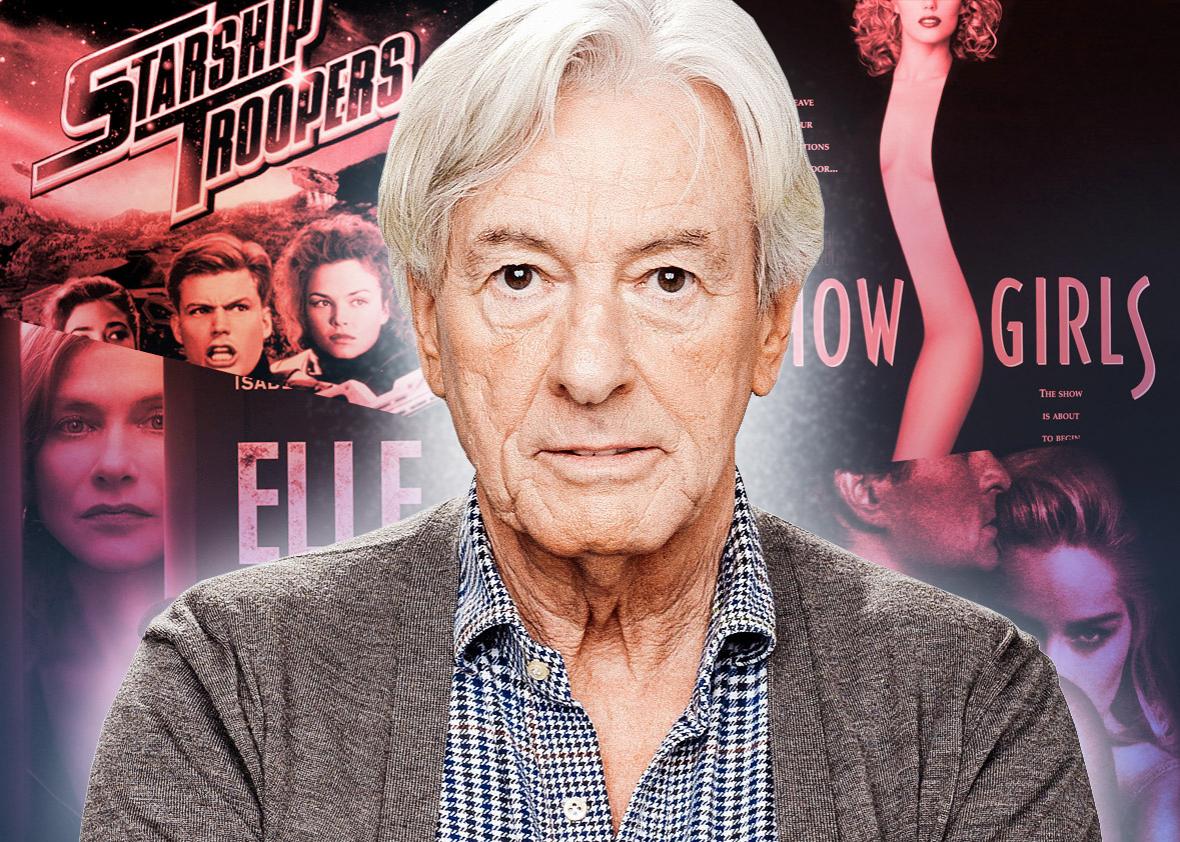

Paul Verhoeven doesn’t care that critics and his twisted legion of fans have “reclaimed” his movies. The director of Total Recall, Basic Instinct, and Showgirls says he knew what his films were doing all along. Why didn’t you?

That might be easy for him to say now. He’s enjoying the best reviews of his career (including from Slate movie critic Dana Stevens) for Elle, his exquisitely deranged French-language thriller starring Isabelle Huppert. France is submitting the movie for the Best Foreign Film Oscar. He’s also been doing a victory lap in New York, where the Film Society of Lincoln Center is currently hosting a full-career retrospective, reaching back to his short films from the 1960s.

But Verhoeven, a contemplative man who still seems perplexed people didn’t understand Showgirls, has no score to settle. At 78, the Dutch-born director is generous and voluble, wandering his way through conversation as if he is curious about what he will say next. (“That’s it, I’m cutting you off,” a hardened publicist told him well after our interview was supposed to end.) We talked last month about why Elle couldn’t get made in America, the Verhoevian horror U.S. politics has become, and his preference to spend time with women over men.

One by one, your American movies have become audience favorites and critical favorites, though they were panned and even protested not long ago. Has that been gratifying?

It’s gratifying, sure. On the other side, I don’t know how important it is really. Making Elle and working on the next movies seems always to be a little bit more important than getting applause about a movie that you did 20, 30 years ago. It’s pleasant, too, that perhaps they exaggerate now a little bit on the other side.

What do you think changed?

These are not the same people that commented in the first place—this is not the generation. It’s growing up in a different political situation, and I think you could say that the movies were probably a little bit ahead of their time. Especially in the case of Starship Troopers—the signals of fascist utopia basically are around the corner now as we all found in the last couple months …

You live in Los Angeles, right?

Yeah.

Are you able to vote? Are you a citizen?

I’m Dutch, and I cannot vote, no. It is forbidden. But if you are really attentive to American politics and you follow it precisely, I mean, it’s scary.

We could use a Verhoeven satire right now.

The satire is already on the street. I don’t know how you can—I don’t know if you can do better than what’s happening now.

I can imagine it.

It’s already near the maximum that you can imagine that the television is basically bringing you news that you would hope to see in a movie. I think you need more time to see what’s happening and reflect on that and how you would reproduce that in an art form. To do that directly is very difficult.

Maybe you see that with Oliver Stone’s recent attempts at it. Snowden was a pretty good movie, but it wasn’t—

No, clearly, because it’s still happening, you know? I mean, he’s still in the news and still Snowden, and you’re competing with something that has already been exhausted here a little bit by the media. It’s difficult to think that you can improve on the reality there. I think that might take 10 years basically. At the moment I think you cannot do that because you’re too close.

You haven’t made an American movie since Starship Troopers in 1997. I read you tried to make Elle in the United States.

Well, from the beginning I thought that this would be an American movie. We translated a novel from French into English and [screenwriter David Birke] wrote an American script situated somewhere in Chicago or Boston or whatever, a North American city. All the characters and the culture was American. Then we were looking for the protagonist, the character, Michèle. American actors didn’t want to have anything to do with this project.

Really? What about Julianne Moore?

[pauses] I cannot talk about that. But that didn’t happen.

Well, I’m glad you made the movie you did. It feels very French for something that was supposed to be American.

It became very French again. When we decided—or were forced to decide, I would say—to go back to Paris, we re-translated it into French. And of course I knew from the beginning that Isabelle [Huppert] probably wanted to do it in the first place. Isabelle had already talked to the writer of the book and the producer before I even joined the project. She wanted to do it basically months before I was there, but we went a different direction, this American road.

In retrospect it’s very difficult to imagine how it would have been as an American movie. I have the feeling that this movie should not have been made at all if Isabelle Huppert didn’t exist.

I can’t disagree.

She brings something to the movie. It’s just something that’s there, and I’m even not sure how much she is conscious of that because she really works very intuitively and follows her talent, whatever way that leads her. I think that she gave something extra to the movie that was absolutely necessary and otherwise, as I said, it should not have been made.

The pairing of you two seems like it should’ve happened a long time ago.

Yeah, but then I didn’t work in France, you know?

You have a tendency to nurture fearless performances in your movies from women in particular. You see that in Basic Instinct, Black Book, Showgirls—whatever else those movies are, those performances are completely invested.

From people or from women? Yes, the last couple of years, it has been a bit female-oriented, the protagonists in Black Book and Elle. But before that, in my Dutch movies [and others], there were of course many male characters that were important and did a really great job. I like to work with actors, I would say.

Of course, I mean, in general I work easier with women than with men. I feel more comfortable with women in general.

Why is that, you think?

I don’t know. Perhaps it’s DNA or perhaps it’s my mother or my father, I have no idea. It happens basically throughout my life that I, in general, prefer basically to sit with women than with men, yeah. Sure. I’m not so much into the macho stuff. I mean, men just often there’s certain competition and this and that, and with women, no.

Growing up basically in Holland there was no separation, male, female—everybody was mixed from the very beginning in the class. It was not male class or female class. I always felt that women and the girls in the class were often superior to the males, to me. They had always [better grades] than I had. That happened in elementary school, that happened whenever I went through high school later, and even when I went to university for my strength as a mathematician, I always felt that they were completely equivalent and often better. And so I grew up as basically seeing no difference between male and female. Yeah, sure, there is a difference, biological difference, but intellectually, culturally, or sociologically …

Well, in your movies—it’s fair to say women suffer a great deal. You certainly see that in Elle.

Evolution makes us the people that we are, or the species we are, which is a species certainly trained in survival. And I think to express that I have used male characters and female characters. I think it’s really more general. It’s really about showing that this species, basically, this ultra-violent species that we are—this animal that’s called human. It’s violent, of course.

But there’s just something very blunt about the violence against women in your movies in particular.

Yeah, because of course—let’s say, especially with the element of rape. If you look at the statistics, they say that someone is raped about 1,800, 1,900 times a day in the United States, so that means a rape a minute. If you express that violence, then you can only express it in what it is. If you aren’t honest about that then I think that’s very dangerous, because then it becomes banal, it makes it smaller than it is. It’s really something where people are traumatized for the rest of their lives.

Even the word sexual assault is already making it less than it is. I think the word rape expresses exactly what it is. If you hear rape, you know you’re talking about brutal violence against women—also men, of course—but if you use sexual assault, that makes it softer. And so, there is in general a feeling that I get in the United States that it’s very dangerous or very not done to use the word rape, which is replaced by sexual assault.

With Michèle, you complicate the violence. She’s raped in the opening scene. Then she enters into a kind of cat-and-mouse game with her rapist, where at some point, it becomes about sexual pleasure.

That’s basically the narrative of that person. It’s this woman, this character that happens to start, say, a masochistic relationship with her rapist, but it’s really that character. By the time that happens, you know who that woman is. The movie tries to give you information about her, about her character, about how she behaves toward other people and in general.

But her motives remain mysterious.

It gives the audience time—let’s say, the possibility to fill in themselves instead of me saying, Wow, this woman is this way and this happened to her and that’s why. We leave gaps for the audience basically to fill in. For me, I think this character is able apparently to follow Jesus’ words, isn’t she? Love your enemy.

In a very literal—

I mean, of course my interest in Jesus plays a part, and I use that consciously. [Verhoeven wrote a biography of Jesus in 2011.] Although the third act refuses to do what perhaps an American movie would generally have. The movie doesn’t go into the more obvious direction of being a revenge movie. It doesn’t do that.

Until the very end.

Ultimately it’s Old Testament, of course.

The interview has been condensed and edited.