How does anyone walk into a classroom and teach a poem after Trump’s win? Across many walks of life it now seems difficult to go back to business as usual. But I’m an English professor, and my usual business is poetry. “Poetry makes nothing happen,” wrote Auden in his memorial to W.B. Yeats, and lessons in the finer points of prosody seem almost perverse in the wake of a campaign that swept to power by flouting introspection, critical thought, and tolerance—all the values central to a liberal arts education.

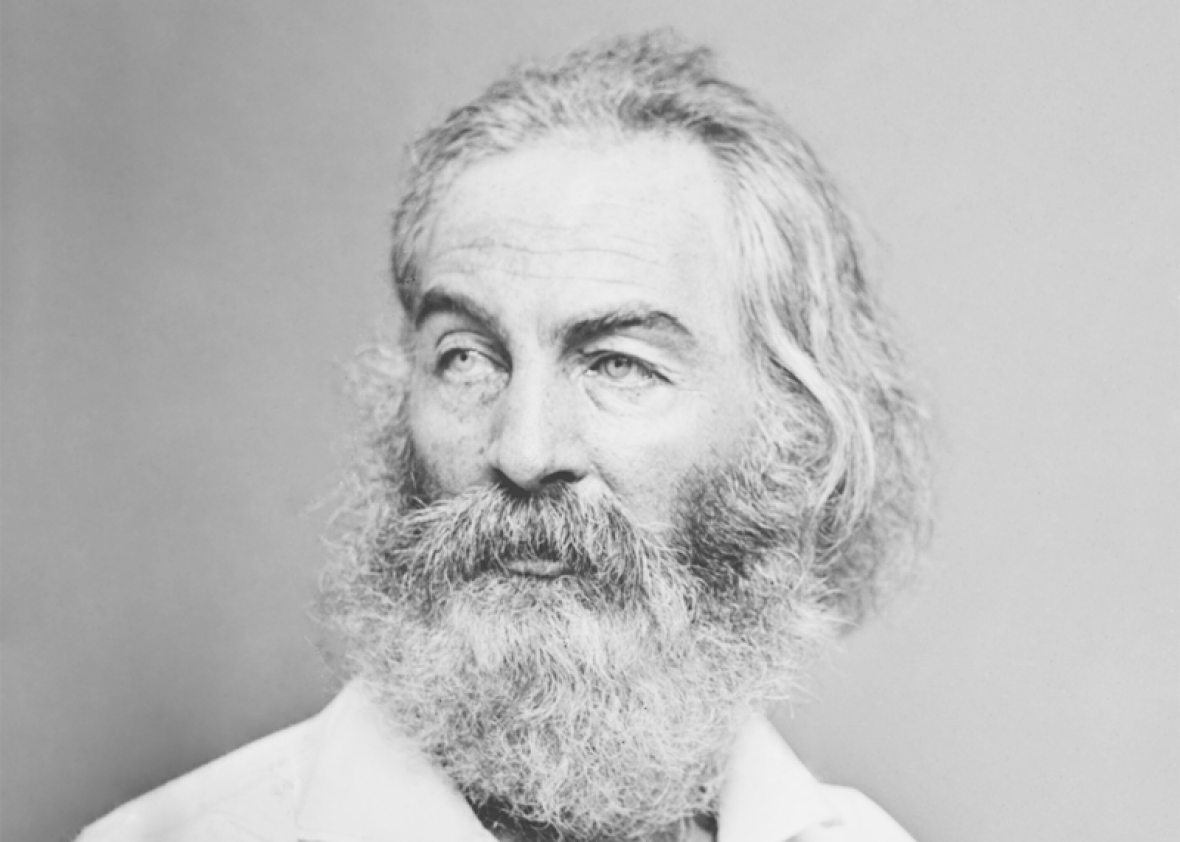

For my first class after the election, I had planned to deliver an upbeat lecture on Walt Whitman and the great American idea of his great American poem “Song of Myself.”

And I know that the hand of God is the promise of my own,

And that all the men ever born are also all my brothers, and the women

my sisters and lovers,

And that a kelson of the creation is love

The poem’s lines stretch past the limit of the page, unbounded, like Whitman’s optimism for the unbounded nature of his young country. A “kelson” is the spine of a ship. It holds things together, like the love Whitman sees uniting all of creation, from the lowliest brown ant to the president, the black ploughman, the “clean-hair’d Yankee girl,” the prostitute, and the poet himself.

Five minutes before I stepped to the lectern to read those lines, my computer chimed with an email notification from the office of the university president, warning that one of the dorms had been vandalized with racist “hate speech.” The same message vibrated across the phones of all 150 students gathered in the lecture hall. It did not feel like we were living in Whitman’s America, and as I started reading his lines, the word love caught in my throat.

Whitman first published his poem in 1855, shortly before the American Civil War, drawing inspiration from the abolitionist movement. In one stanza the speaker recalls how he had given shelter to a runaway slave “and brought water and filled a tub for his sweated body and bruised feet.” In this American epic, unlike the classic epics of Homer and Virgil, the heroic model is not the triumphant soldier but the radical Jewish teacher who would be crucified shortly after washing his disciple’s feet.

Regaining my composure, I managed to tell my students that Whitman was perhaps too eager to believe that the real America was the one that gave succor to the slave rather than the one that enslaved him, the one that “put plasters on the galls of his neck and ankles,” rather than the one that fought to keep him in chains. For context, I read a passage from Whitman’s contemporary Elizur Wright, a fierce crusader against slavery who saw slavery as America’s original sin. Each generation that continued to profit on the original act of oppression, he wrote, “may well be said to inherit their father’s sin—they commence the business of sinning not like their father, upon their own resources, but with an accumulated and fearfully productive capital.” Wright looked to America’s future and sees not hope but wrath. “As generation after generation passes away,” he continued, “the curse of God grows heavier, and the thunders of his coming wrath swell to a louder tone.” If President Obama had given us hope that we were living in Whitman’s America, President Trump had reminded me that we were also living in Wright’s benighted land, and I ended my lecture in record time with the classic refuge of a teacher with nothing more to say: “Any thoughts or questions?”

After a long pause, one student raised her hand. She noted that Whitman’s own racial attitudes were complex and that in many ways he did not transcend the prejudices of his time. At times he seemed to think of blacks as a less evolved race, “and yet I think it is inspiring that, even though he was an imperfect vessel, he was able to articulate a vision of America in which we were all one.” Another student added that this vision was related to Whitman’s celebration of the body. “Welcome is every organ and attribute of me, and of any man hearty and clean, / Not an inch nor a particle of an inch is vile.” Discovering the value of his own body, the poet found a metaphor for the body politic that was more inclusive than the positions he would take in prose.

This prompted one more student to add that while the poem had been published without a title in 1855, and was called “Walt Whitman” in 1860, it had finally become “Song of Myself” when Whitman published it again in 1881. “It became a song of ‘myself’ that is also open to all selves,” she added, and then we turned to the idea that these selves were united on the most fundamental level of being, a shared humanity rooted in our shared life on the planet. “Every atom belonging to me,” Whitman writes, “as good belongs to you.”

By 2020, every student in the room will have graduated. If Trump and his party keep even a fraction of their promises, America will be a very different place than it is today. Trump has promised to appoint a majority of Supreme Court justices who will unwind rights for women, minorities, and homosexuals. Millions more people will lack health care, and student debt will continue to grow, especially as the new administration eviscerates Obama’s regulations against predatory scams like Trump University. My students, in other words, will have their work cut out for them, and even though teaching poetry may not seem like our most pressing national concern, I’m very glad my students will have it.

In the same poem where Auden wrote that poetry makes nothing happen, he said the poet could “with the farming of a verse / Make a vineyard of the curse.” Poetry isn’t politics. But as my students helped remind me, it can be the fertile soil for our better selves. The final lines of Auden’s poem, written in 1939, as the world lurched to war, have never been more vital:

In the deserts of the heart

Let the healing fountain start,

In the prison of his days

Teach the free man how to praise.